What a pleasure to read around in the Paris Review archive of poems from its pages. I experienced anew the capriciousness of taste and the ardor of individual decades. As the guest editor of the Review’s daily poetry newsletter this week, I chose poems that I consider keepers for my lifetime. All are by poets I read avidly in my twenties and thirties, when I was still unformed and seeking liberators. For me, Baudelaire, Miłosz, Walcott, Gregg, Glück, Wright, and Schuyler are masters in the craft of language. Their words (assembled into art) transport me. Even now, at sixty-five, I am always looking for new liberators. Thank goodness poetry is unkillable. Thank goodness poetry is continually renewed by a rediscovery of the past, by new translations, and by the ache of the young.

Listen to Henri Cole read his selections here, and read his commentary below.

“It Is the Rising I Love” by Linda Gregg

This poem is a glorious representation of the mind and soul of Linda Gregg, who died in 2019. When her first book, Too Bright to See, was published, I was in my twenties. With its strange innocence that seemed to have symbolic meanings, it captivated me. I value the neat way her poems communicate the darkness that surrounds mankind. As Joseph Brodsky said, her poems have a “blinding intensity,” like “lightning” or “heartbreak.”

“The Crystal Lithium” by James Schuyler

James Schuyler is my favorite New York School poet. “The Crystal Lithium” is the first of his great, long-lined, long poems. “All six senses are at play, plus those of tone and form,” as James Merrill observed of this shy poet’s wonderful poems, which prove that a “ ‘reverence for life’ doesn’t have to be boring.” Readers of this poem should remember that lithium compounds, known as lithium salts, are used as a psychiatric medication, primarily for bipolar disorder.

“Figs” by Louise Glück

Louise Glück is a marvelous poet. There is so much effortless intelligence in her poems. In just a few lines, she creates a tone with the peculiar power to draw us deeply in. “Figs” is so sharp and clear a narration, so ravishing it seems to declare simultaneously something familiar yet new about the journey of one soul, about the pulse of the earth, and about the ebb and flow of marital love.

“The Sea Is History” by Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott was my teacher. It’s difficult for me to be objective about this magisterial poet. I first read ‘The Sea Is History’ as a young man, in Walcott’s beautiful book The Star-Apple Kingdom, a book with a public dimension that traces Antillean history. Among other things, Walcott is a master of simile, and I love his lamenting seafarer’s tone. For me, his poems reestablish poetry’s responsibility to our common, troubled, historical past.

“Lying in a Hammock at a Friend’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota” by James Wright

This free-verse sonnet is, of course, inflected by Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” The explosion of Rilke’s concluding line—“You must change your life”—becomes, in James Wright’s poem, “I have wasted my life.” The simplified beauty of his language and its truth-telling seem to me as enduring as classical Chinese poetry. I’m so grateful for the dark turn this poem makes at its finish. A man’s life is not a thing to sentimentalize.

“My Faithful Mother Tongue” by Czesław Miłosz

Years ago, when I lived in Japan, the country of my birth, I felt most at home in the bookstore aisle of publications in English. For Czesław Miłosz, a great servant of the Muses, the Polish language was his home, but he recognized that it was home, too, to “informers,” to the “debased,” and to the “unreasonable.” Still, Miłosz remained faithful to his mother tongue, for it was also for him a place of incarnation and renewal.

“Epigraph for a Banned Book” by Charles Baudelaire

I grew up reading Richard Howard’s translation of Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal, and it remains for me the standard version, even at its campiest, fiercest, and most theatrical. I adore Baudelaire’s breach of decorum, his openness to sorrow and tenderness, and his spleen. A hundred and fifty years later, his poems sound to me so original and contemporary.

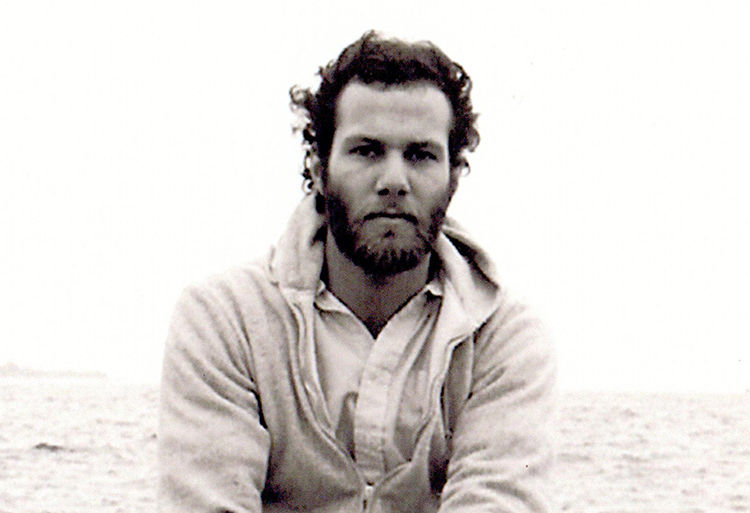

Henri Cole was born in Fukuoka, Japan. He has published ten collections of poetry, most recently Blizzard, and a memoir, Orphic Paris. A selected sonnets is forthcoming.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/fAgVvha

Comments

Post a Comment