Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

“Often when I teach my poetry workshop,” Claudia Rankine tells David L. Ulin in her Art of Poetry interview, “I will take essays or passages from fiction or a scene from a film and list them among the poems to study. The ‘Time Passes’ section in the middle of To the Lighthouse is an example of a lyric impulse. Others might be a passage from James Baldwin or Homi Bhabha or an image by Glenn Ligon or a song by Coltrane.” As National Poetry Month draws to a close, we’ve been wondering what really makes a poem a poem, so we decided to consult a few experts. Draw your own conclusions from Adam Zagajewski’s “My Favorite Poets,” Gordon Lish’s “How to Write a Poem,” and a vibrant portfolio of artworks by the poet and painter Etel Adnan. And here on the Daily, you can listen to Henri Cole, whose poem “The Other Love” appears in our Spring issue, read some of his favorites from the Review’s archive, which he selected for his takeover last week of our daily poetry newsletter.

INTERVIEW

The Art of Poetry No. 102

Claudia Rankine

As a poet, I want to use language to enter that space of feeling. I’m less interested in stories. That’s one reason I write poetry.

From issue no. 219 (Winter 2016)

PROSE

How to Write a Poem

Gordon Lish

I tell you, I am no more interested in poetry than the next fellow is. I mean, I can take it or leave it. On the other hand, once in a blue moon I come across a poem whose unfolding holds me for the distance. Not that it must be a very good poem, in mine or in someone else’s opinion. On the contrary, my enthusiasm is entirely a function of my hoping to detect a key insufficiency in a poem of no particular merit, of my intuiting a certain turning where the poet’s nerve—forget intelligence—failed him.

From issue no. 82 (Winter 1981)

POETRY

My Favorite Poets

Adam Zagajewski

Sometimes they knew

what the world was

and wrote hard words

on soft paper

Sometimes they knew nothing

and were like children

on a school playground

From issue no. 226 (Fall 2018)

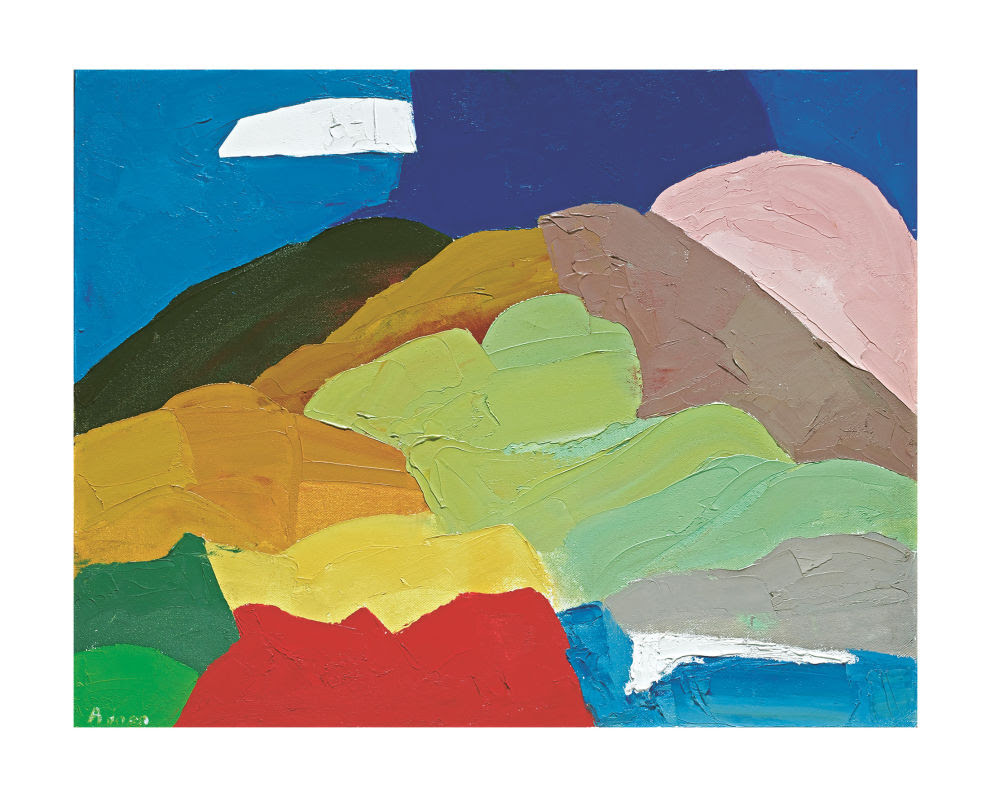

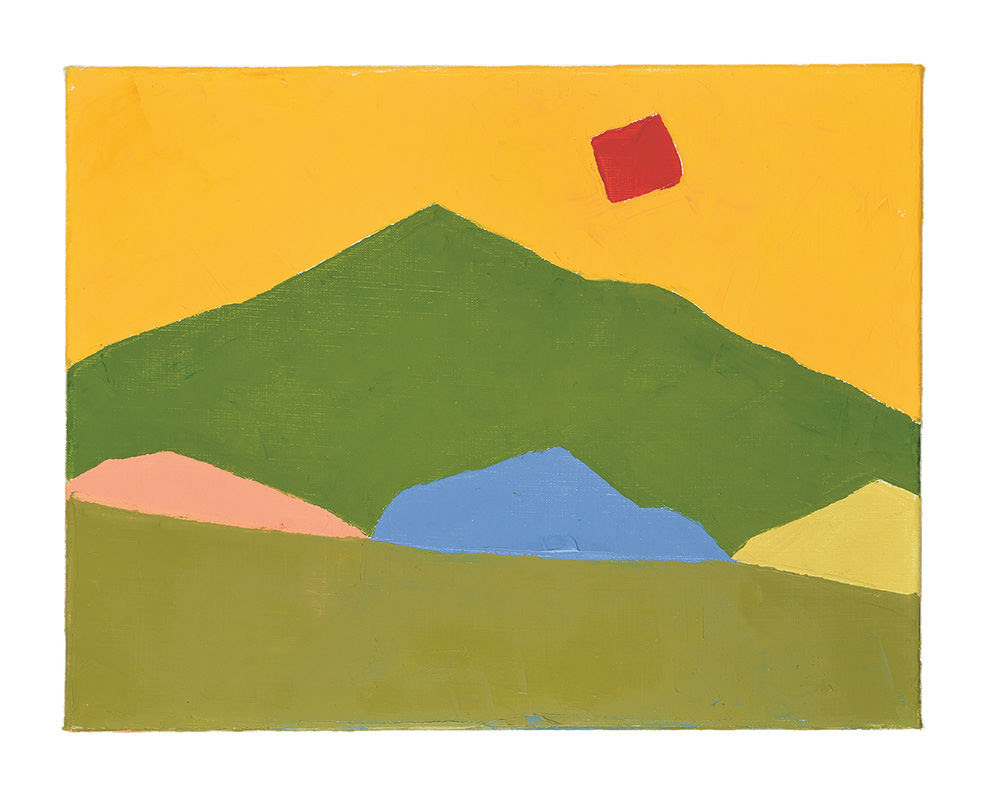

ART

The Shape of the Mountain

Etel Adnan and Nicole Rudick

When the war for Algerian independence began in 1954, she became hardened against the French language, in which she had been writing poetry. “Painting,” she says, “opened to me a different way of expression. And as my Arabic was poor, in some moment, as a defiance, I happened to say, I will paint in Arabic!” The California landscape awakened her spiritual instincts and focused her gaze. While living near Mill Valley, she had daily views of Mount Tamalpais. “To observe its constant changes became my major preoccupation,” she has written. “I even wrote a book in order to come to terms with it—but the experience overflowed my writing. I was addicted.”

From issue no. 224 (Spring 2018)

If you enjoyed the above, don’t forget to subscribe! In addition to four print issues per year, you’ll also receive complete digital access to our sixty-nine years’ worth of archives.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/sPB0ZWg

Comments

Post a Comment