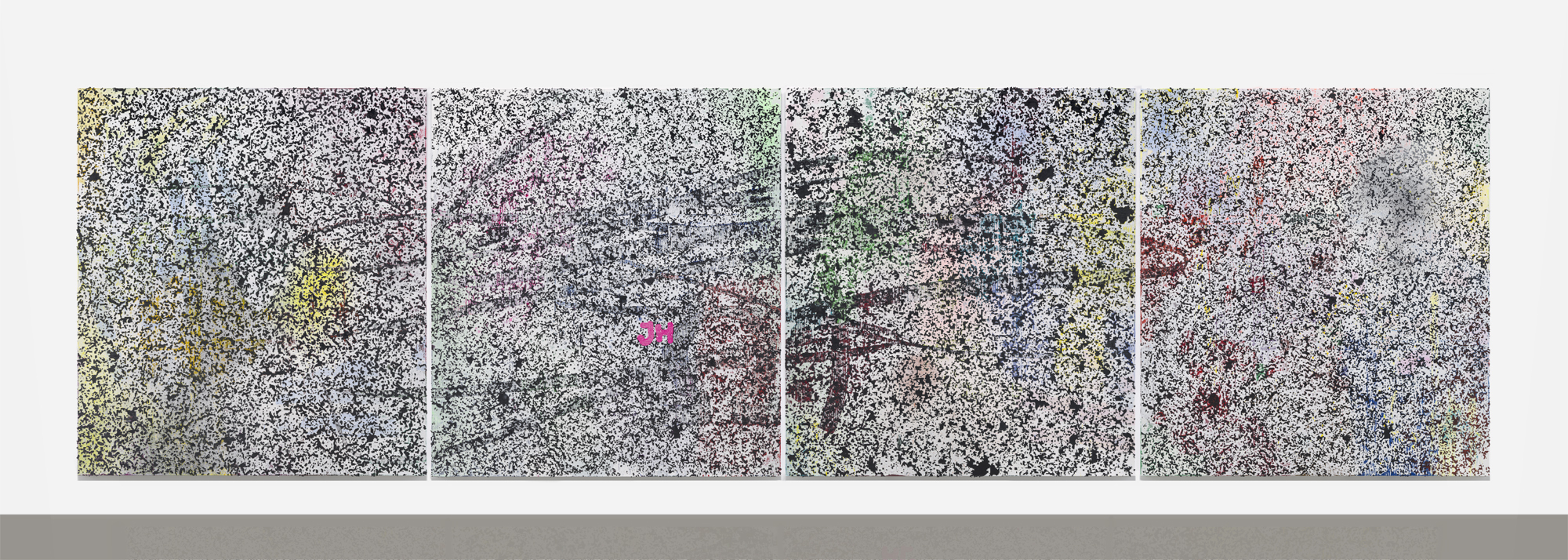

Jacqueline Humphries, omega:), 2022 (detail). Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

My mother is a Renaissance historian who specializes in Venice and paintings of breastfeeding; her books and articles have subtitles like “Queer Lactations in Early Modern Visual Culture” and “Squeezing, Squirting, Spilling Milk.” I have an early memory of her taking me to a Venetian church to see Tintoretto’s Presentation of the Virgin, a depiction of a three-year-old Mary being brought before the priest at the Temple of Jerusalem. The child Mary is shockingly small. Dwarfed by a stone obelisk carved with faint hieroglyphs, she ascends a set of huge, circular steps inlaid with abstract golden swirls. Onlookers crowd around, including three sets of fleshy women with children who dominate the scene and who, my mother explained to me, are likely wet-nurses. Breastfeeding women are often allegories of caritas: Christian care. This vision of femininity—as carnal, and as both literally and figuratively nurturing—reappears, centuries later, virtually unchanged, as the central conceit of Cecilia Alemani’s 2022 Venice Biennale, “The Milk of Dreams.” In her selections, the woman’s body once again serves as a breeding-ground for personal and political metaphors, and the artist’s relation to her own embodiment as cornerstone of her creative practice.

Alemani’s show, which includes an unprecedented eighty percent women artists from the highest number of nations in the Biennale’s history, was wide-ranging, surprising, and often exciting. But the corporeal interpretive framework that “Milk of Dreams” insists on was disappointing in its failure to imagine (imagination being another theme of the show) a new future for feminine forms of expression. The description for every single subcategory of the main exhibition references “hybrid bodies,” “corps orbite,” “somatic complexity,” et cetera. Even the work described to me as “abstract” was mostly vaguely suggestive of womblike figures. There was a lot of fan art dedicated to Donna Haraway, whose Cyborg Manifesto once offered a revolutionary vision of embodiment—but was published nearly forty years ago. If the work wasn’t thematically body-related, it likely involved a textile, a well-known medium for women (often worn on bodies). And though many of the “leaves, gourds, shells, nets, bags, slings, sacks, bottles, pots, boxes, containers” (this is the actual title of one of these sub-exhibitions) were really quite cool, it’s frustrating to be told to relate to oneself solely as some version of a clay pot, even a subverted one.

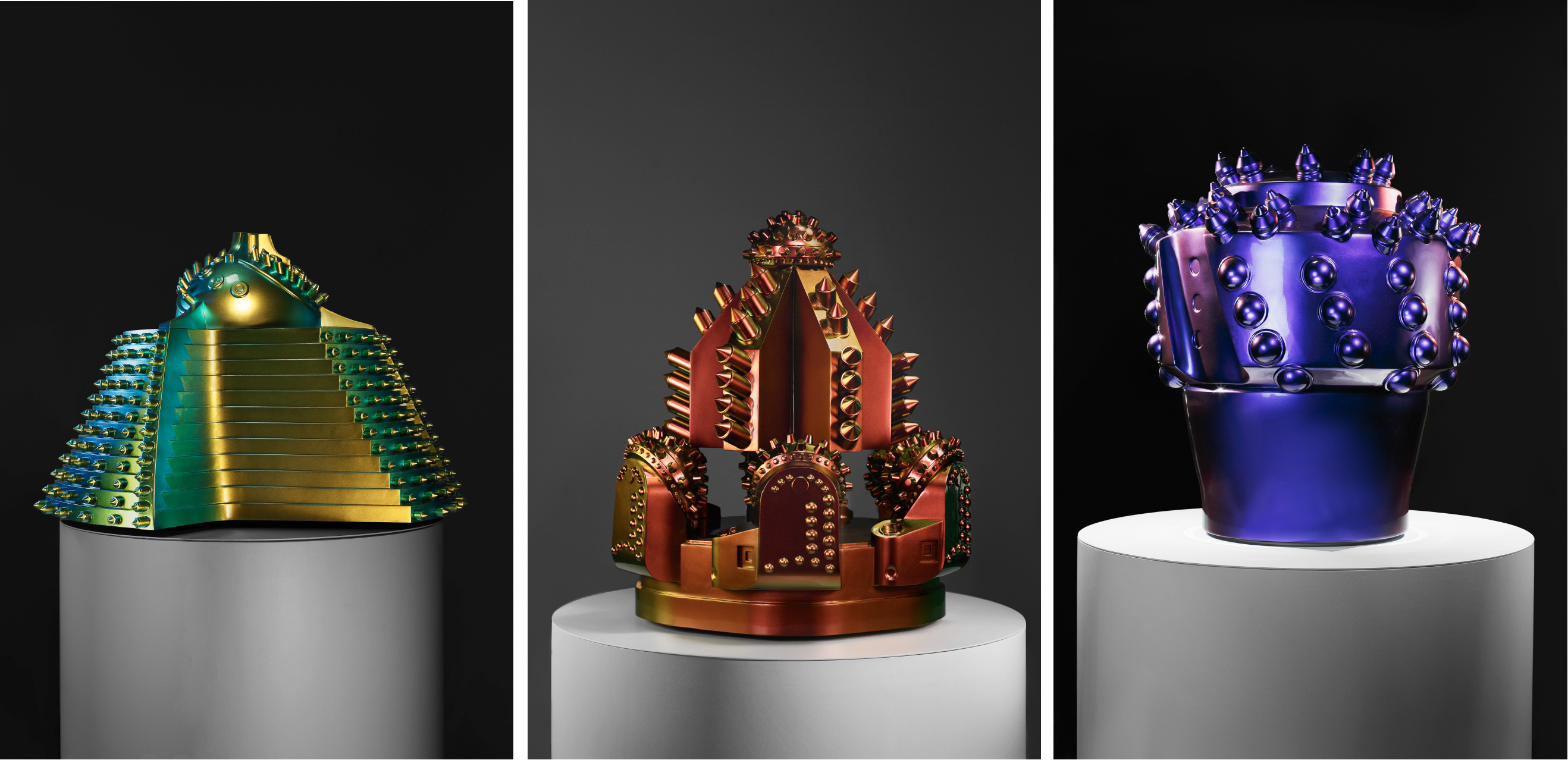

Among the artworks less mired in the biomorphic, I liked: Jessie Homer French’s folk-arty paintings of climate disaster transposed into flat, Wes Andersonian landscapes, including one in which pixel-like stealth bombers glide over desert shrubs and windmills; Monira Al Qadiri’s shimmering, slowly rotating, jewel-toned sculptures inspired by the Gulf region’s “petro-culture,” which resemble rococo drill bits hypertrophied into palaces; a sensorial maze by Delcy Morelos, made out of dense cubes of soil, cacao, and spices, which was somehow both comforting and uncanny; and Jamian Juliano Villani’s painting of a traffic light submerged in a whirlpool of foliage. Her goat wearing UGGs was great, too, and perhaps the only nod towards the girly in the show. There’s a video by the Chinese artist Shuang Li, which seems to be narrated by human (?) manifestations of digital images or pixels, in a series of surreal statements formulated with the narrative simplicity of religious or mythological texts. The strangest sequence features a chubby white girl illuminated by a fluorescent ring light eating chicken fingers (perhaps our Mary at the temple), whose moving image simultaneously tunnels into and spirals out of itself, until the ring light appears to be the entrance to a psychedelic well, or a black hole (of YouTube).

Easily most impressive, though, was Jacqueline Humphries’s massive four-panel abstract painting omega:). From afar, it gives an impression of colors moving very quickly, like a glitch radiating for one second across a torrented video. But up close, it’s painstakingly precise, composed of many shapes, similar yet irregular, somewhere between the rectilinear patterns on QR codes and the organic mottle of army camo. They’re intensely black, and tactile, with multiple layers of red, green, yellow, and blue paint underneath them that contribute to the vaguely migrainous feeling I had of hallucinating colors into a black-and-white image. (There were also two smaller paintings by Humphries, composed of small black Xs and dashes, like ASCII characters, to similarly hypnotic effect.) Stepping back and forth between the two scales gave me a more genuinely “dream”-like sensation of three-dimensionality, movement, and digitality than any sculpture or video in the show. Several people told me that they liked these paintings but that they were clearly out of place in the exhibition, given Alemani’s theme, which, in addition to the orgy of bodies, focused on surrealism—highly literal figurations of the content of dreams. Humphries’s paintings, instead, stimulate or simulate the feeling of unreality by playing at the edges of perception itself, through masterful manipulations of form. And her gesture towards femininity is pleasurably abstract, too: omega:)’s focal point is a set of gloopy, sparkly letters, bright pink, in the rounded style favored by middle school girls—her own initials, JH.

Jacqueline Humphries, omega:), 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

On my last day in Italy, I saw Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, a cycle of frescoes dating to the early fourteenth century, and a masterpiece which doesn’t need a review from me. But it’s worth describing the drama of technology and timing through which the experience was staged. Upon arriving in the verdant park surrounding the chapel, you are first led into a glass cube affixed to the small stone church. You sit, on transparent plastic chairs, in this “Corpo Tecnologico Atrezzato” for more than fifteen minutes, during which time your body humidity is lowered and cleansed of smog particles, so that your visit will not harm the fragile paint in the chapel; this is explained in one of two videos shown to you on a small flat-screen. The second video is an explanation of the stories in the paintings, melodramatically inflected by the Italian narrator, and is underscored by stirring music; this prepares you spiritually for the images. Once purified in mind and body, you are allowed to exit this space station and, for twenty minutes, enter the chapel itself, which feels, by then, like a time-travel machine. In the chapel, surrounded by the white-noise sound of ventilation technologies, you can feel the compression of hundreds of years of human history—and the future, too.

In addition to that of Christ, Giotto’s frescoes depict of the life of Mary. Motherhood and care are all very well; “the body” is certainly important. But there’s also the Virgin, who is certainly a vessel, but actually far less corporeal than her bleeding, perspiring, emotional-labor-performing, dying son. Even as the breastfeeding Madonna Lactans, she usually looks detached, almost plasticene, more like a meditative Renaissance Barbie than a mother. One likes to imagine her preoccupied with the heavens, with her ideas. In Giotto’s Annunciation, as in most, she is reading alone in her room. (Mary is understood to have been studious.) And, in an amazing final trick of circumventing her body, rather than die, she simply ascends.

Olivia Kan-Sperling is assistant editor at The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/aYb03gi

Comments

Post a Comment