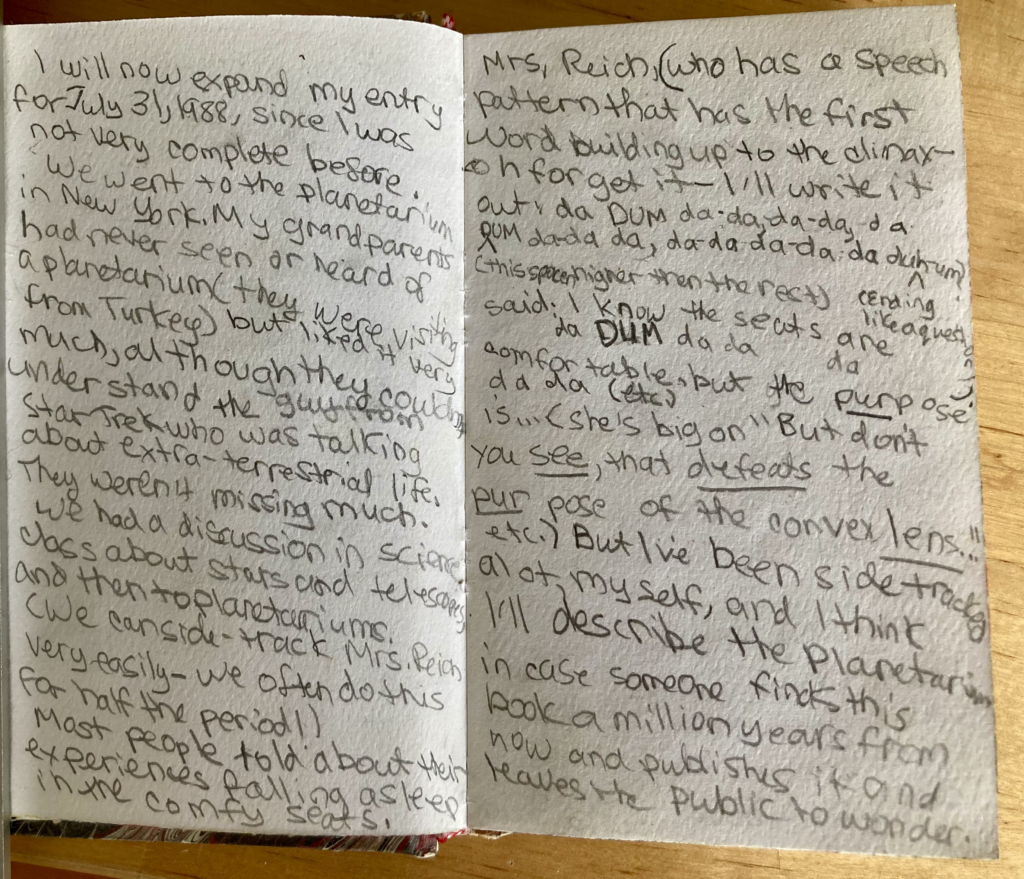

Last year, when my mother moved apartments, I came into possession of a largeish Prada box full of my childhood diaries. They go from 1981—I was four, and dictated the diary to my aunt—up to the nineties. I still haven’t read most of them. (I think it was a handbag, and not a small one, that originally came in that Prada box.) It is hard work to feel love for one’s childhood and adolescent self. Reading this entry, for example, I feel ashamed at my eleven-year-old self’s American imperialistic attitude towards my grandparents, who hadn’t heard of a planetarium before but “liked it very much.” It’s interesting that I then apparently felt I had to explain the concept of a planetarium for the benefit of people “a million years from now.” The whole entry gives me a “dutiful” feeling, when I read it now. I think I used to feel like I had to be writing all this stuff down, maintaining a chatty, “delightful” style, explaining every last thing down to the speech patterns of my fifth-grade science teacher, and appealing to some kind of “universal” reader who would understand it all and give each detail its proper value (although apparently this person also wouldn’t know what a planetarium was). What even is a childhood diary—for whom do we keep it?

Elif Batuman’s first novel, The Idiot, was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Its sequel, Either/Or, will be published on May 24.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/s0DdnSj

Comments

Post a Comment