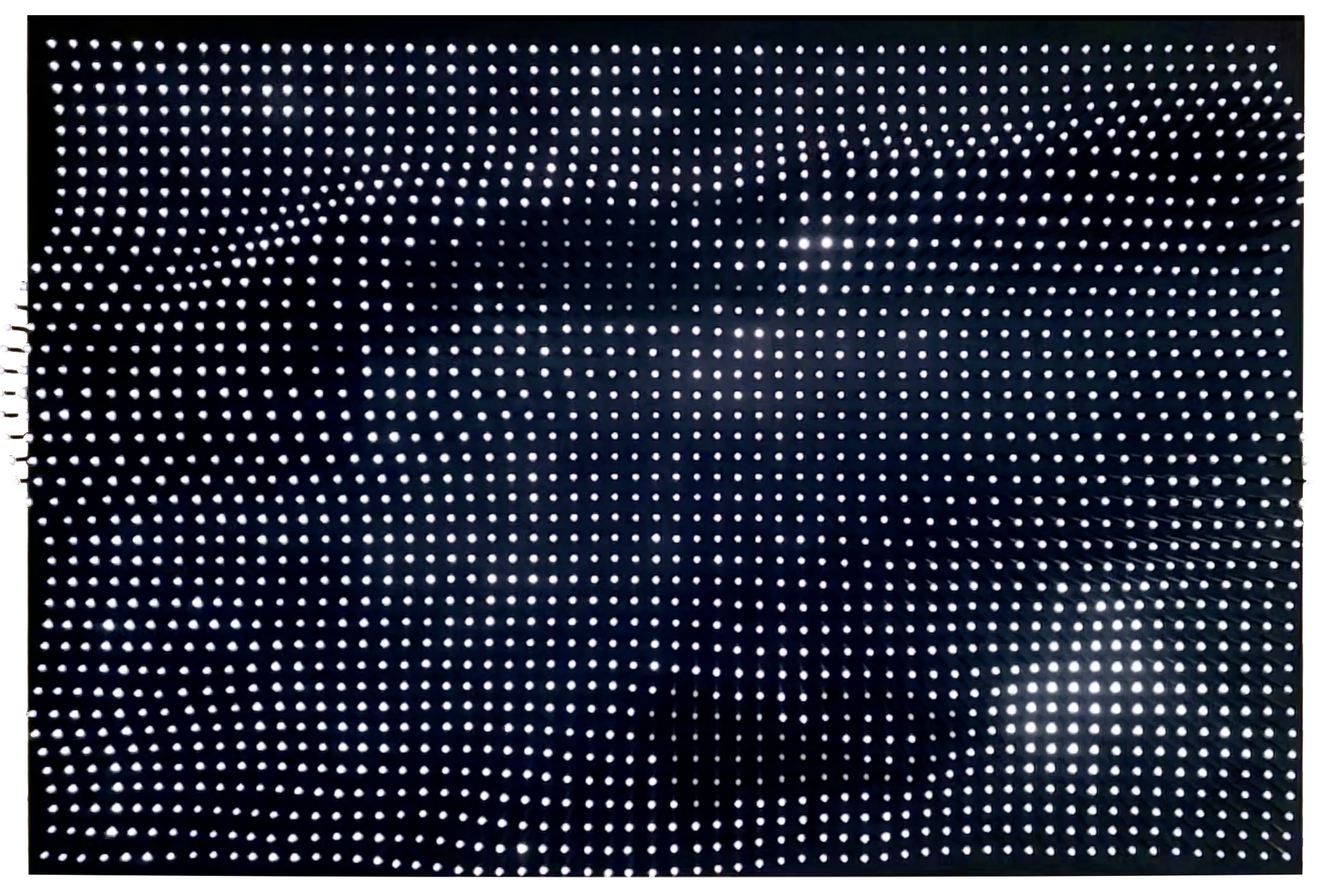

“Empire of Water,” on view until May 30 at The Church in Sag Harbor, New York, is well worth a wander out east. The exhibition, cocurated by the Church cofounder and artist Eric Fischl and the chief curator, Sara Cochran, features watery works from forty-two artists including Warhol, Ofili, Lichtenstein, Longo, and Kiefer, and an Aitken that delights. But the cake stealer is hiding in the back corner of the first floor: Topographic Wave II, by Jim Campbell. Tucked behind a partial gallery wall are 2,400 custom-built LEDs of various lengths mounted on a roughly four-by-six-inch black panel and arranged neatly in a tight grid, like a Lite-Brite for grown-ups or a work of Pointillism by robots with OCD. From a small distance, images appear as shimmering figures swimming through Pixelvision water. Walk closer and the picture dissolves into fragmented dots blinking some unrecognizable pattern. For a short time I paced in front of it, goofily leaning in close then stepping back. Distantly, I recalled an instruction to squint when viewing Seurat, so I did that, too.

—Joshua Liberson, advisory editor

Caren Beilin’s Revenge of the Scapegoat is a weird book, in the best possible way. The novel follows Iris, a Philadelphia-based adjunct, as she flees for the countryside after she receives a series of letters from her past, penned by her father, who blames her for a familial crisis that occurred in her teenage years. There’s a sense of gleeful rampage. “Bonkers” is probably the best way to describe Beilin’s writing, which is full of madcap, often darkly funny digressions about publishing, the art world, chronic illness, complicated family dynamics, and the traumatic legacy of the Holocaust. “A book should be like a lot of spit,” Iris declares early on. “You can get an artist to live at a concentration camp easy,” another character says later in the book, about artist residencies, “if there’s a super streamlined application process.”

—Rhian Sasseen, engagement editor

This past week I’ve been reading Shola von Reinhold’s debut, Lote, a heady novel that explores, in multiple genres and forms—comedy of errors, writing-retreat novel, book within a book—the erasure of Black art from gallery walls, history books, and archives. The novel’s narrator, Mathilda Adamarola, is fascinated by the London-based artists and socialites of the twenties known as the Bright Young Things. She’s itinerant, in thrall to decadence, possessed of multiple names, a researcher dilettante. With a little deception and luck, she is admitted to a writing residency honoring the work of John Garreaux, a fictional theorist whose work emphasizes a kind of aesthetic rigidity and blankness our hero despises. She revolts against the residency’s conspicuous rules, but falls prey to some of its subtler machinations, and Von Reinhold’s sensual sentences unfurl like ethereal greenery as you read.

Concurrently, I’ve been reading some plays Harold Pinter wrote in the seventies that are also very British and concerned with nostalgia. The one that really had me in its teeth was No Man’s Land, which opens with a conversation between a wealthy British writer named Hirst and a much younger and less established poet named Spooner. The two have returned from the pub together, and act as if they just met. But the play’s second act embarks on a new premise: that Hirst and Spooner have known each other for years, and that their lives are deeply entwined … or maybe not so deeply. Like Lote, the text veers from intimate to alienated in an instant. Everyone talks at cross-purposes; some of what they say is nearly nonsense. The characters’ misapprehensions of one another’s language are so large that a drama of word association ensues, unbeknownst to the speakers. The humor could not be drier, as when Hirst bemoans, “I do not understand … how the most sensitive and cultivated of men can so easily change, almost overnight, into the bully, the cutpurse, the brigand. In my day nobody changed. A man was.”

—Hannah Gold

Read Hannah Gold’s interview with Will Arbery on the Daily here.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/7yTD5Ej

Comments

Post a Comment