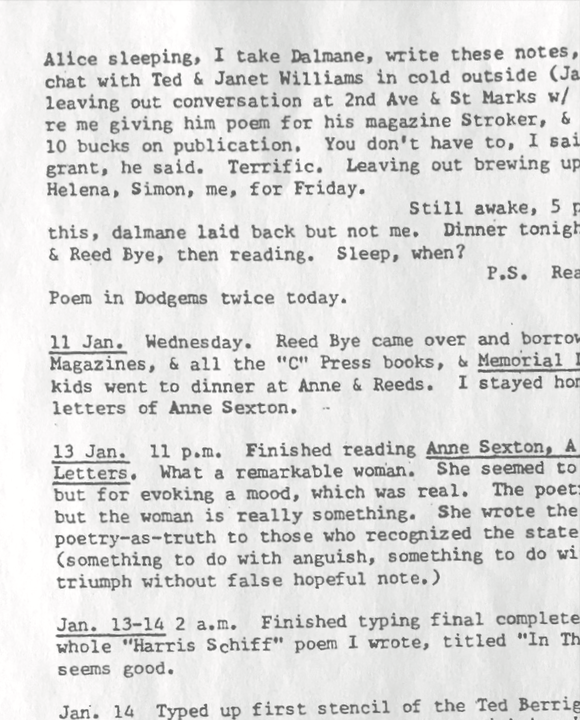

My father, Ted Berrigan, is primarily known for his poetry, especially his book The Sonnets, which reimagined the traditional sonnet from a perspective steeped in the art of assemblage circa the early sixties. He was also an editor, a publisher, and a prose writer—specifically one who worked in the forms of journals and reviews. While his later journals were often written with the expectation of publication—meaning the journal-as-form could be assigned by a magazine editor—his sixties journals are much more internal. In these journals, he’s writing to document his daily life and his consciousness while figuring out how to live, and how to live as a poet, so to speak. These excerpts from his journals were originally published in Michael Friedman’s lovingly edited Shiny magazine in 2000. They were selected by the poet and editor Larry Fagin, who invited me to come to Columbia University’s library, where my father’s journals from the early sixties are archived, and work with him on the selection process. We were looking, as I think of it now, for moments of loud or quiet breakthrough—details, incidents, and points of recognition that contributed to his ongoing formation as a person and poet.

“The Chicago Report,” which narrates a weekend trip from Iowa City to Chicago to attend a reading by Kenneth Koch and Anne Sexton put on by Poetry magazine, was written in 1968 in the form of a letter to Ron Padgett, a close friend and fellow poet. It was later published in an issue ofThe World, the Poetry Project’s mimeographed magazine, as well as in Nice To See You, an homage book put together by friends after my father’s death in 1983. It may be recognizable as an affable, freewheeling, and at times incendiary piece of first-person satire, filtering the voice of “Ted Berrigan” through the voice of Ted as known by Ron, or vice versa. My father was a working-class Korean War veteran who didn’t feel comfortable in high-class literary circles but did engage them at times, with amusement and a kind of gentle predilection for disruption.

—Anselm Berrigan

January 1961

Whatever is going to happen is already happening.

—Whitehead, Aims of Ed.

Sunday, February 5

I suppose this situation is revealing concerning the kind of person I am: at my brother Rick’s wedding yesterday, four of my aunts, all about 15 yrs older than I, began to question me about why I am no longer a Catholic. Two of them were very antagonistic; they seemed to be personally offended by my beard and my disaffiliation from the Church. I tried to answer their questions intelligently, but in everything I said I actually had the secret but entirely conscious idea in mind of impressing my beautiful, shy, wide-eyed 14-yr-old cousin, dtr of one of the aunts, who was also sitting in the group.

February 6

At moments when things seem to crystallize for me, when life comes together for a minute, when what I am sensing, thinking, reading, ties together for a magic moment of unity, along with the instant desire I have to tell Chris [Murphy], or Marge [Kepler], or the beautiful girl I met yesterday somewhere, comes the simultaneous thought that I am the only one who can know what I mean. My girls must be real—not symbols.

[undated]

Ron [Padgett] & Harry [Diakov] & I forged a prescription for Desoxyn. Harry stole it from the Columbia dispensary, Ron wrote it out, and I took it to the drug store & had it filled. No trouble.

The pills are like Dex & Bennies, less after effects than Bennies. They make me nervous, awake, “high” if I allow myself to get out of control.

Great to take them, go to movies, pour over the movie like a poem or book … Makes for total involvement with a consciousness of it.

March 4

Heard Allen Ginsberg read last night at the Catholic Worker Hdqtrs in the Bowery. The reading was on the 2nd floor of the Newspaper office, in a kind of loft. The place was jammed, nearly 150 or 200 there. Ginsberg wore levi’s and a plaid shirt, anda grey suitcoat. His hair is thinning on top, and he is getting a little paunchy. He wore thick black rimmed glasses, and looked very Jewish. He is good looking, intellectual appearing, and was quiet and reserved, with a humorous glint in his eyes.

He read Kaddish, a long poem about his family and the insanity of his mother. It was a very good poem, and a brilliant reading. Ginsberg reads very well, writes a very moving driving line; and the poem contained much dialogue. Ginsberg seems to have a perfect ear for speech rhythm. The poem was based on Jewish Prayers and was very impressive in sections, with a litany-like refrain.

There was much humor in the reading, much pathos, and all in all, it was the most remarkable reading I’ve ever heard, very theatrical, yet very natural. Ginsberg was poised and assured, like a Jazz musician who knows he’s good. At the end someone asked him what meter the Poem was in and he replied, Promethean Natural Meter.

*

Sitting alone in Ron’s room at Columbia.

I make a vow—I will try even harder from now on to be a realist. To see. To penetrate the Personae of the world. To be in harmony with my will. To fully develop both my ability for practical reason, and for speculative reason, the methodologies of the tripartite will.

Tuesday, March 6

… It was one of those nights when it was good to be alive. I had slept all day. Started working at ten. At four I went out for Coffee. The heat goes off in our place at 12, and stays off until six. But it wasn’t too bad last night. It was raining slightly outside and the air was cool as I walked through the dirty, empty streets in the Bowery, to the all-night Cafe, a half mile away. My mind was full of thoughts about my thesis, about Hobbes four-fold division of Philosophy, about writing to [Dick] Gallup discussing his plans for the next yr. of coming to school here, of Pat getting my letter, of getting a job, enrolling in school, and many others. It struck me that I was happy. Everything, for a brief moment, was amalgamating, and had purpose—

Those moments are rare for me. Much of the moment can be attributed to Desoxyn. I take one or two a day, work fifteen or sixteen hours, reading, typing, planning. And Desoxyn keep[s] me alert, and keep[s] my weight down—in the face of my starchy diet—But it was a spontaneous feeling nevertheless. Even recalling my days in Tulsa, the days in 1959 when I nearly broke down, did not dampen it.

March 13, 9 P.M.

. . . While in Providence [in 1959], doing nothing except reading, writing bad poems, and brooding, I slowly came to the conclusion that the best thing I could do in life was to strive for saintliness—that is, to try to be kind to everyone, to hurt no one, to be humble, and to be as much help to people as I cd, by being sympathetic, a listener, a friend. This attitude was brought on by my observation of everyone’s unhappiness.

Excerpt from “The Chicago Report”

THIRD DAY

Sunday afternoon. I wake up at 3. Tired, but feeling good. Smoke some chesterfields, turn on the tv. Detroit is playing Baltimore.

The motel restaurant is too expensive. So, we pack our things, smoke the last of the pot, and check out.

Taxi to the bus station, and put our things in a big locker.

Digging the streets. Dig the Picasso sculpture. Dig WIMPY’S, where we dig the cheeseburgers. Henry says, “They have WIMPY’S in Paris and London, too. I saw them.”

Then, into another taxi, and off to Paul Carroll’s. We debate whether or no to take the acid now. Before dinner, or after dinner? After. OK.

At Paul’s Henry kisses the hostess, and we have a delicious dinner, with fellow guests Jim Tate, the Yale Younger Poet for 1967, and Dennis Scmitz, the Big Table Prize Poet for 1969. Dennis Schmitz has the flu and can’t eat. Paul Carroll is warm & friendly in his inimitable manner, and I kind of have a good time. His apt. is nice, roomy, lots of painting and photos and books and green plants and light. His wife is terrific, I finally decide.

Jim Tate I like, but could easily not.

So, dinner gets finished, and its off to the University of Chicago, to hear the two poets of dinner read. Henry and I secretly decide to take the acid. We do.

Paul introduces the poets. They read. Tate isn’t bad, but not that good. He’s wild ok, but wild academic, which is only mildly interesting. Dennis Schmitz is ok, but his poetry is boring. We wait for the acid to hit us, and eye the girls. I think of Tony Walters. There is only one beautiful girl, a soft blonde girl with a purple dress.

The reading gets over, we start for a party. We will have to leave soon, to catch a 12:30 bus to Iowa City.

The acid hits. Totally freaked out but maintaining a calm exterior, I enter the little apt where the party is. Woolworth’s furniture, no interesting paintings, everybody shy, not too many people, wine. I have some wine and bread, sit in a chair, a big easy chair, smoke a chesterfield.

Henry heads straight for the beautiful girl in the purple dress. I lose track of him. I am suspended between an acid trip and a party. I drop the burning end of my cigarette into the depths of the chair. I try to put it out. I think Isucceed, but just in case, I move over to the couch. Hundreds of hours pass. Henry and the girl disappear. I drink some wine,most of the people have gone into other rooms. A young kinky blonde girl about 17 comes and talks to me. I mention Korea, and she says, “I wasn’t even born then.” I say, terrific.

I notice people are carrying cups of water over and pouring them into the chair. Very interesting. It seems to be smouldering. I hear someone say “. . . don’t know how it happened.” I forget it.

Paul Carroll comes over and says, ride downtown? I say, what time? He says, 11:45. I say, ok. Then I say to Jim Tate: Tell Henry, Bus. He says ok.

We go. The ride downtown is sensational, I take millions of rich warm side trips. After years we get to the bus station and have the Irish goodbye scene. I can hardly keep from bursting out laughing.

Then, into the bus station. Inside, its horrible. I shudder, and begin to feel a little sick, a little lost, a little scared, a little crazy.

In my back pocket are postcards. I think: mail. It takes me hours to get the stamps but I do, lick them, & then go outside and mail the cards. Then I know I am a great competent guy, just a soldier on leave in a strange city like lots of other times and nothing to fear. But Chicago faces are ugly.

I cross the street outside the bus station in the rain, and go to contemplate the Picasso sculpture. By now I am tired (tho I wasnt then) so I will not go into the incredible things I had happen in my art brain there. Then, back to the bus station, Henry arrives,zonked, but happy to see me.

We buy tickets, and have 15 cents left. Get bags, get on bus.

Long interesting mild & thoughtful bus trip to Iowa City, to arrive at 6 a.m. Monday morn- ing, disturbed only once pleasantly when Henry got off bus and bought us M&M’s.

Iowa City. I get off, shake hands with Henry, say, see you later, I’m going home. He grins and say, see you, I’m going into the bus station and this beautiful girl I met on the bus here is going to buy me coffee.

See you.

Love,

Ted

City Lights Books will publish Get the Money! Collected Prose (1961-1983), from which these selections are drawn, in September.

Anselm Berrigan’s most recent book is Pregrets. He is the poetry editor for The Brooklyn Rail, and the editor of What Is Poetry? (Just Kidding, I Know You Know): Interviews from The Poetry Project Newsletter 1983-2009.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/5IEDuy6

Comments

Post a Comment