This week, we bring you reviews from four of our issue no. 240 contributors.

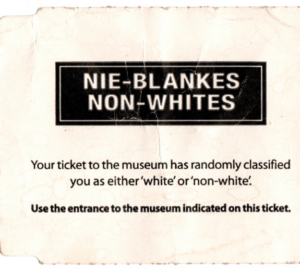

Journeys at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. Photograph by TrudiJ, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

I went to Johannesburg in 2013, I don’t know why I’m telling you about it now. Maybe because lockdown is a kind of segregation, where you see only the people you live with. Dilip picked me up at the airport. Driving into town, he left a car’s length between his Toyota and the car in front. I noticed other vehicles doing the same. We don’t want to be carjacked, he said, they box you in and smash the windshield. The seminar began the next day, and I was at my seat at 9 A.M., jet-lagged and medicated. I nodded off during Indian Writing in English: An Introduction. Later, I vomited in the staff restroom, left the university building, and went toward the center of the city. In the wide shade of an overpass, I walked into a smell of barbecue meat that would stay in my clothes all day. There were people drinking beer, blasting cassettes, selling fruit and cooked food from tarps spread on the ground. In the car Dilip had said apartheid was a thing of the past, but wherever I went I saw people segregated by habit. The days passed so slowly that it felt like a long season, like summer on the equator. I saw people in groups, some kind of shutdown in their eyes. I saw a man kneeling in the middle of a sidewalk. Why we got to go out there? he wailed. Why? I had no answer for him. At the Apartheid Museum, the random ticket generator classified me correctly among the NIE-BLANKES | NON-WHITES, and I entered through the non-white gate. The museum was designed to provoke. Of the exhibitions, documents, photographs, and pieces of film footage I saw there, only the installation Journeys stays with me now, a decade later. In 1886, when gold was discovered in Johannesburg, migrants came to the city from every part of the world. To prevent the mixing of races, segregation was introduced in both the mines and the city. Journeys is a series of life-size figures imprinted on panels and placed along a long, sunlit walkway. These are images of the children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren of that first wave of migrants. By walking among these people of all races, something you have done countless times in the cities of the world, you are part of a subversive tide of art and history, an intermingling, the very thing apartheid was created to prevent.

—Jeet Thayil, author of “Dinner with Rene Ricard”

I am excited by Jennifer Elise Foerster’s new book of poetry, The Maybe-Bird (Song Cave, 2022). The long title sequence “repurposes language from eight texts written by explorers or Indian Agents to Creek County from 1527 to 1828.” I find the resulting quilt of poems intensely lyrical and compelling. The final section opens with these memorable lines:

The waiting room where no one waits

opens at the edge of a field. What do you see,

being rowed across, weightless as you are?

The earth suspends its one inky eye.

I peel back the surface of the water:

fish in your blood skimming the blade.

—Arthur Sze, author of “Zuihitsu”

Recently, I was looking for a documentary by Lithuanian director Mantas Kvedaravičius, which just won an award in Cannes. But instead, I found his first film about this Ukrainian seaside city (Mariupolis, 2016), a city which is currently occupied by Russian troops. I turned it on, and couldn’t turn it off.

The first thing you catch while watching Mariupolis is sound. It surrounds you, coming in waves, lifts you to a great height and slowly lowers you to the flat surface of the calm everyday. In the film, musicians rehearse: violin sounds. Women working on trams talk about their work tomorrow. “Don’t worry, they promised not to bomb,” one says. A girl catches a fish on a hook, screams with delight, and at the same time asks her dad to release the fish back into the sea. Later, we see a journalist reporting from a building damaged by an explosion. Oh, the explosions, I thought, and felt strange. So this is how war becomes a part of the everyday. Did the bombs fall into the sea? No one had paid them any attention.

Several Ukrainian militiamen smoke and joke. Their intonations, accents, and even languages are different. But their mood is good. You see the macabre fragments of Soviet life scattered here and there, alongside people’s vivid smiles, eyes, conversations, and music. You can physically feel these sounds fill the space around and inside you. It’s as though you’re intuiting this city, Mariupol, completely and wordlessly.

Mantas Kvedaravičius was killed by Russians in Mariupol in April 2022.

—Katrina Haddad, author of “There is Nowhere to Go Back To”

Let me draw a crooked line for you, from The Paris Review, the first literary journal I ever bought—off a magazine rack in a candy store in Cranford, New Jersey, circa 1970 (I confess I hoped it might be a skin mag which also published poetry)—to my newest discovery: Apofenie, a literary journal edited by Kate Tsurkan, an NYU PhD candidate currently living in Chernivtsi, Ukraine (the hometown of Paul Celan, Olha Kobylianska, Aharon Appelfeld, and Gregor von Rezzori), where she has become a potent force in bringing to the literary agora a whole range of voices too long in the margins of our awareness. The work in its pages is always lively and quickening.

—Askold Melnyczuk, translator of “There is Nowhere to Go Back To”

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/WJ1z0cr

Comments

Post a Comment