To mark the appearance of Leonard Cohen’s “Begin Again” in our Summer issue, we’re publishing a series of short reflections on his life and work.

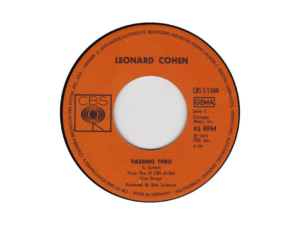

When Leonard Cohen starts singing “Passing Through” on his 1973 Live Songs album, he sounds tentative, like a child who’s been asked to sing a song he learned at school in front of a party of adults. “I saw Jesus on the cross, on a hill called calvary … ” On the record his voice is faint—I’ve spent twenty years turning up the volume—and he sings so casually that it sounds like he really might have seen the crucified Christ, and asked him, deadpan and impertinent, “Do you hate mankind, for what he’s done to you?” Jesus has a pretty mellow, Jesus-like response, delivered in Cohen’s increasingly confident baritone: “He said ‘Talk of love not hate—things to do, it’s getting late.’” He is, like the rest of the Biblical and historical characters Cohen will encounter throughout the song, only passing through. Compare Cohen’s line readings to the declamatory, bugged-out delivery that Dylan gives to the opening lines of his bible pastiche “Highway 61 Revisited.” Cohen is calm, weary, a little resigned; Dylan is providing color commentary at the Belmont Stakes.

Cohen didn’t write “Passing Through,” something I didn’t know until a week ago. The gentle, straightforward melody and slightly hokey lyrics about George Washington and Franklin Roosevelt probably should have given it away as the product of a forties folk socialist songbook that it is, but with Cohen, it’s often hard to be sure what level of irony, if any, we’re dealing with. “Passing Through” builds in strength and spirit as it goes along, Cohen’s perfectly ramshackle country band and backup singers providing a reasonable and sincere-seeming simulacrum of a gospel revival. He puts some extra oomph into the climactic, clumsy sentiment: “Yankee, Russian, white or tan / He said a man is still a man / We’re all on one road, and we’re only passing through.” The audience claps along on the final chorus. Does he mean it? At least as much as Roger McGuinn and Gram Parsons mean it when they sing that they “like the Christian life.” Which is to say, absolutely, for the length of the song.

The song’s feverish, distended mirror image, “Please Don’t Pass Me By (A Disgrace)” appears on side two of Live Songs. I’ve always heard it, because of its placement and linguistic echo, as a response to “Passing Through.” Another sing-along, it replaces the earlier song’s sanguine assurance that all suffering is temporary with an urgent and disturbed plea not to let things go, to remain alert to the world’s agony and injustice, from a blind man on the corner in New York City to “the Jews and the Gypsies and the smoke that they made.” He vamps and ad-libs for almost thirteen minutes. Things get increasingly personal and intense as the song goes on: “I know that you still think there’s somebody else. I know that these words aren’t yours. But I tell you, friends, one day, you’re gonna get down on your knees. You’re gonna get down on your knees … ” He repeats this nine times, then hollers the chorus in desperation as his backup singers half-heartedly try to cushion the mood with their harmonies. The performance segues into a self-annihilating monologue directed at the audience: “My friends, take my dignity. Take my form. Take my style. Take my honor. Take my courage. Take my time, take my time … ” He sounds like a man in crisis, clinging to something slipping away. As the song peters out, the band and singer exhausted, the audience roars.

I don’t doubt, in this case, his level of sincerity. It was the third time he’d played the song live, and he never played it again.

Andrew Martin is the author of the novel Early Work and the story collection Cool for America.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3uVafAr

Comments

Post a Comment