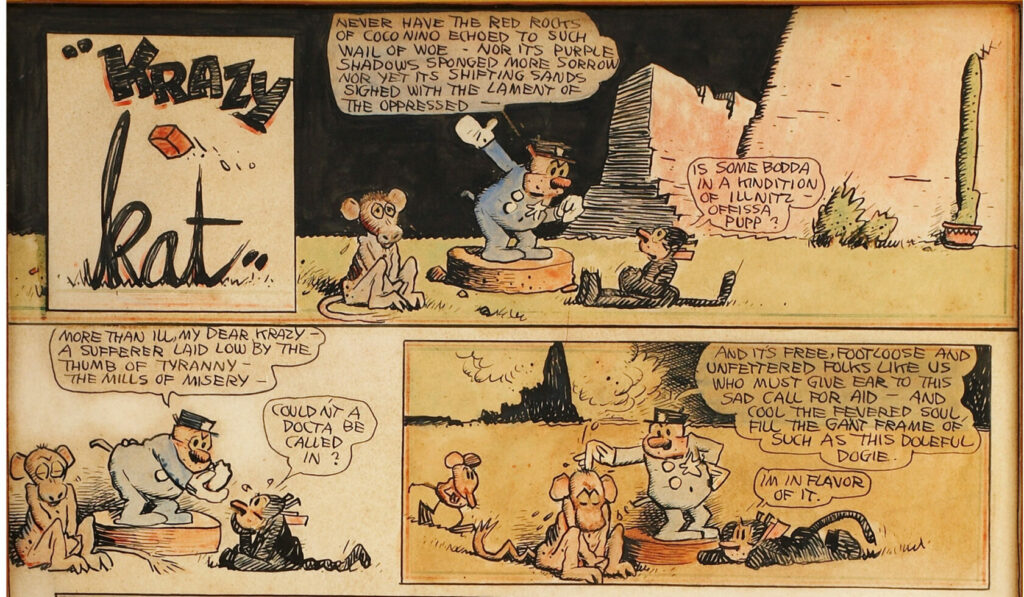

<em>Krazy Kat </em> by George Herriman.

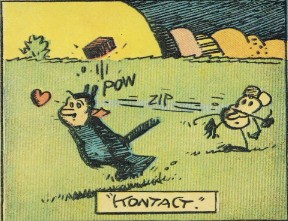

In 1910, a mouse named Ignatz first beaned Krazy Kat with a brick. The plot of this comic strip, centered on a “heppy go lucky kat,” is simple. Krazy Kat loves Ignatz Mouse. Officer Pup loves Krazy Kat. Ignatz Mouse hits Krazy over the head with a brick; Officer Pup pursues and usually arrests Ignatz Mouse; Krazy, to whom the brick seems to be a sign of love, is ecstatic. A small heart pops up above his head. The cartoonist, George Herriman, twisted and tangled the three-lover triad and cat-mouse-dog triad and spent thirty-one years retying the same surreal knot. You know what will happen in any strip of Krazy Kat—the same sequence reoccurs eternally—but somehow there is still room for unexpected delight.

E.E. Cummings was one of the Kat’s biggest fans. In 1922, he wrote from Paris to request clippings from friends in America. (“Thank you moreover for a Kat of indescribable beauty!” he wrote to an obliging friend.) In his 1946 introduction to the first edition of the collected strips, Cummings wrote that the brick unleashed joy within the “ultraprogressive game” of the real world, with its preestablished rules, of which it flouted the most sacred: “THOU SHALT NOT PLAY.” (Winnicott defines play as “the continuous evidence of creativity, which means aliveness.”) Herriman gives pleasure without the instant gratification of a punch line, undercutting the expected gag trajectory. The brick hurtling across the page doesn’t end the joke; games end, but play is infinite. There is no winner, and if there is, it is Krazy, who, for private reasons, interprets the brick as love.

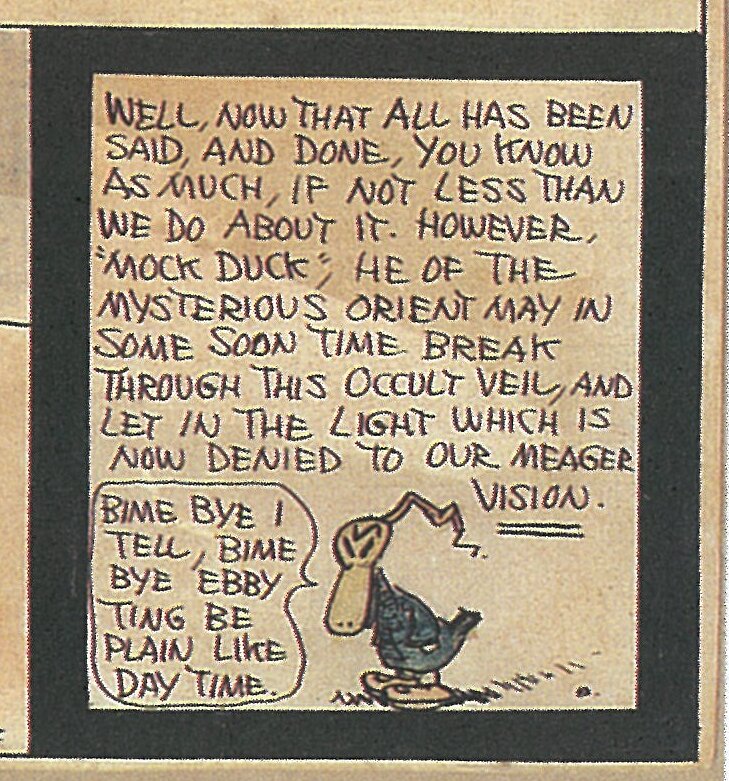

The strips were published daily in Hearst newspapers between 1913 and 1944, but Herriman never repeated himself. Or at least, the strip didn’t look the same. The improbable landscape of Coconino County, Arizona, where the strip is set, seems almost to move on the page. Bill Watterson, the creator of Calvin and Hobbes and a Herriman megafan, wrote, “Mountains are striped. Mesas are spotted … The horizon is a low wall the characters climb over … The moon is a melon wedge, suspended upside down.” Herriman juggled all the elements the form allowed: language (hyperbolic Creole, Spanish, Yiddish); comedy (existential, vaudevillian, burlesque); and gender—the Kat is neither he nor she, but rather, as Herriman put it, “a pixie,” whose pronouns switch within a strip and occasionally within a sentence, making the possible configurations and miscommunications of the comic infinite. Somehow, in this static form, nothing is inanimate. Only a killjoy would try to extract too much meaning from Krazy Kat, but it’s not surprising that Herriman created art that depended on fluid identities. Twenty-seven years after Herriman died, the sociologist Arthur Asa Berger published the birth certificate on which Herriman was registered as “col,” for “colored.” Herriman was born in New Orleans in 1880 to a mixed-race family that moved to Los Angeles ten years later and from then on passed as white. Herriman had plenty of reasons to keep it up, including his job at the Los Angeles Examiner, a publication that regularly outed people for their race, and the fact that he lived with his white wife in a neighborhood with racist housing covenants. Telling different stories at different times, Herriman explained his light brown skin as the result of years spent living under the Greek sun to some people and claimed various ancestries—often French—to others. (As Krazy tells Ignatz, “Lenguage is that we may mis-unda-stend each udda.”)

The Kat had a cult following among the modernists. For Joyce, Fitzgerald, Stein, and Picasso, all of whose work fed on playful energies similar to those unleashed in the strip, he had a double appeal, in being commercially nonviable and carrying the reek of authenticity in seeming to belong to mass culture. By the thirties, strips like Blondie were appearing daily in roughly a thousand newspapers; Krazy appeared in only thirty-five. The Kat was one of those niche-but-not-really phenomena, a darling of critics and artists alike, even after it stopped appearing in newspapers. Since then: Umberto Eco called Herriman’s work “raw poetry”; Kerouac claimed the Kat as “the immediate progenitor” of the beats; Stan Lee (Spider-Man) went with “genius”; Herriman was revered by Charles Schulz and Theodor Geisel alike. But Krazy Kat was never popular. The strip began as a sideline for Herriman, who had been making a name for himself as a cartoonist since 1902. It ran in “the waste space,” literally underfoot the characters of his more conventional 1910 comic strip The Dingbat Family, published in William Randolph Hearst’s New York Evening Journal. Hearst gave Herriman a rare lifetime contract and, with his backing, by 1913 the liminal kreatures had their own strip. Most people disliked not being able to understand it. Soon advertisers worried that formerly loyal readers would skip the strips and miss the ads. Editors were infuriated by devices like Herriman’s “intermission” panel, which disrupted the narrative by stalling the action. There was also just the sheer strangeness of some of his characters, such as Mock Duck:

For Cummings, who, with his flagrant anti-intellectual stance, privileged what he called “Aliveness” above all else, Charlie Chaplin was the only artist to rival Herriman. But technology disrupted both Chaplin’s and Herriman’s idiosyncratic work. At the introduction of sound in film in 1927, Chaplin said that the “spontaneity of the gags had been lost,” but what he really lost was his control of time. Sound erases distance; there was no longer a delay in which the incongruity between seeing and comprehending could bloom. In his essay “What People Laugh At” (1918), Chaplin noted “the liking of the average person for contrast and surprise in his entertainment.” Both Herriman and Chaplin orchestrated meticulously timed, silent dialogues between images and words. Slapstick—a word that originally referred to two pieces of wood joined together, used by pantomime clowns to make loud noises—is, in their work, a deliberately clumsy cleaving of the relationship between words and images. If people could explain themselves, there would be no time to revel in ludicrous situations, as when in The Kid, Chaplin, caressing the hand of a policeman’s wife, is accidentally caressed by her husband.

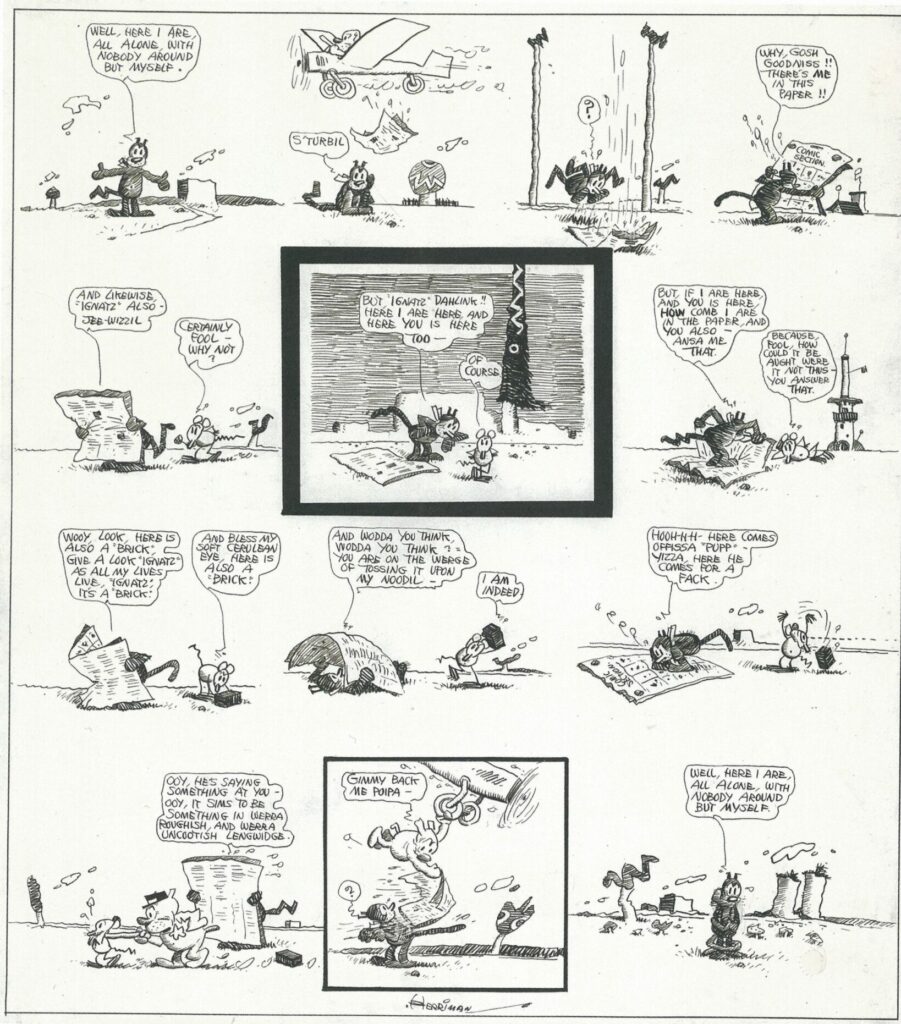

T.S. Eliot commented that Chaplin had escaped “in his own way from the realism of the cinema and invented a rhythm.” This rhythm in Chaplin’s work is a personal tempo. Chaplin has perfect control of his own time; his bodily movement controls the rate at which the story unfolds. Rhythm is an acoustic metaphor for a visual form with its own internal logic, and it is evident too in Krazy Kat, where it creates an elastic, almost spatial experience of time rather than a narrative one. Chaplin and Herriman’s work presents discrete moments that appear as part of the same present, although they are not serial narrative; they create strange, self-contained temporalities.

Many criticized Chaplin for resisting the lure of sound, but in a 1940 letter, Cummings wrote, “I like Charlie Chaplin as is and my lightning raw”—no accompanying thrum of thunder. Cummings understood that sound could kill play; he once said, “Not all of my poems are to be read aloud.” The 1922 ballet Krazy Kat: A Jazz Pantomime, based on Herriman’s strip, was a flop for the same reason: it robbed the reader of the internal, private experience of making connections between frames. (Likewise, a series of attempts to animate Krazy was a disaster.) It’s funny when Krazy misreads signs we can see, because there’s an ironic distance; both meanings are there at once. With sound, Herriman’s wit was reduced to a series of quips and the crash of a brick hitting a cat.

I first encountered the Kat in my early twenties, trying to wean myself off Cummings’s love poetry by reading his letters. Heartbroken and too raw for new experiences, I took comfort in the strange repetition of each strip. In 2020, in between lockdowns, I started prowling the internet again for the Kat. The strips felt very of the moment; I couldn’t escape my awareness of how quickly time was passing and how few things it took to fill it up. I was bored, but in the acutely happy moments, eating with friends, or when my friend’s baby held a phone to her ear and then to her doll’s ear—a baby on a phone holding a baby on a phone—I didn’t want anything to change. No news was good news. Repetition seemed like a space in which creativity could thrive.

Part of the reason the strip didn’t catch on more widely is that it isn’t easy to read quickly. Because of the changing layout, scattered phonemes, and rotation of themes in Herriman’s strips, you can’t read them left to right or in a hurry. Spatially, the strip defies the linear progression of a gag, both in the way we read—sometimes the brick hurls against us, whizzing from right to left—and in the uneven panels, which defy chronology. In one of my favorite strips, Krazy reads Krazy Kat. Naturally, he is astounded. He says, “But ignatz dahlink!! Here I am here, and here you is here too.” Ignatz, ever superior, replies, in a nonchalant pose: “Of course.” The panel is delineated and thickly framed, emphasizing Ignatz’s comfort within the cartoon world; by contrast, in the next frame Krazy jumps up and down on the paper (“but, if I are here, and you is here, how come I are in the paper, and you als—ansa me that”). Ignatz’s pose is then rotated so that he lies on his side, in exactly the same construction of lines, and replies, “Because, fol, how could it be aught were it not thus—you answer that.” Here, like Krazy, we are perplexed. We cannot answer. Ignatz raises an eyebrow.

Cummings also sought to control time by manipulating space in his poems. For this reason, he disliked technology, particularly the Linotype, which he saw as intruding on his freedom. In one plaintive letter to his aunt Jane, he writes about the urgent need to “retranslate 71 poems out of typewriter language into linotype-ese,” which “inflicts a pre-established whole—the type ‘line’ on every smallest part; so that words, letters, punctuation marks & (most important of all) spaces between these various elements.” The Linotype’s enforcement of the linear destroyed the potential space within the typewritten poems for chance collisions and a hidden choreography of readerly eye movements. In 1920, after reading a book asserting that the eye remains in constant motion, Cummings scrawled excitedly: “THE EYE MUST NEVER STOP.”

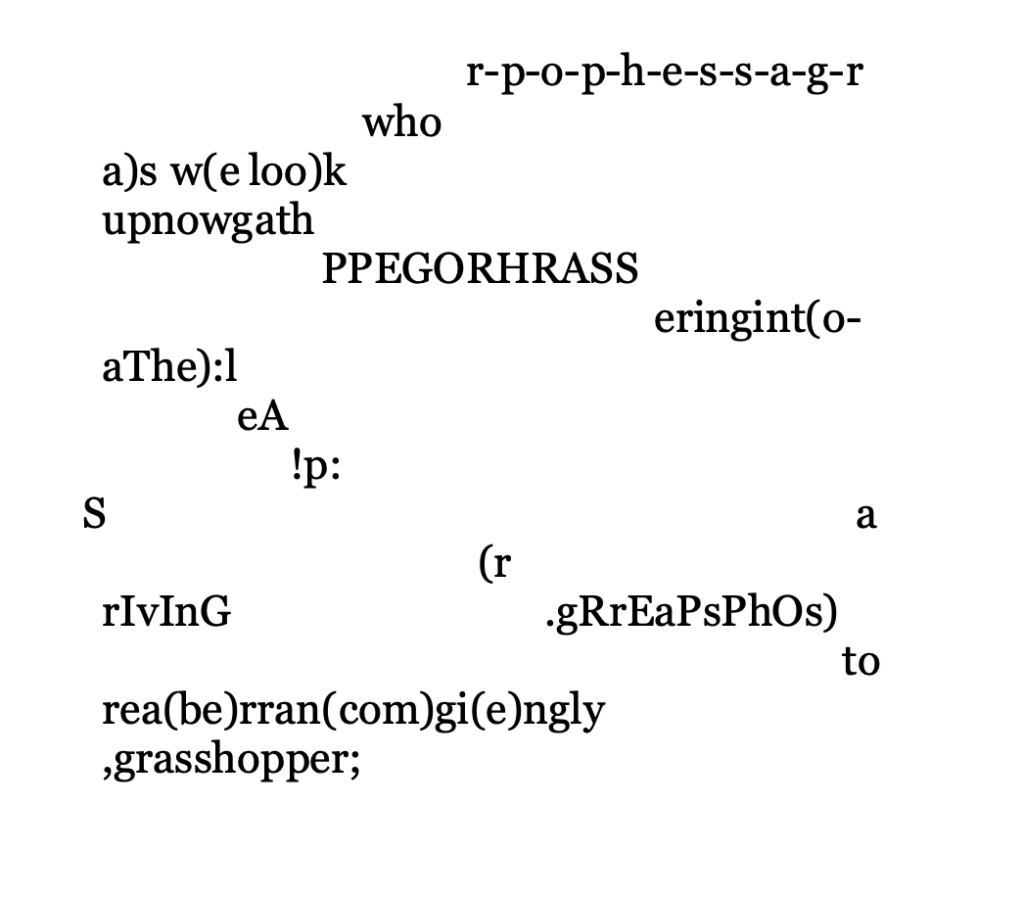

Ironically, the digitization of Herriman’s strips has improved the experience of reading them. We read differently on screens; we’re used to tabs, pop-ups, watching movies, toggling around. As I discovered during lockdown, having hijacked the huge monitor my boyfriend’s company sent him, these digital versions of Herriman’s strips preserve their strange logic; technology doesn’t interfere with the artist’s control of time but lets us read vertically and horizontally at once. Gazing at them on the screen made me realize why Cummings felt such a kinship with Herriman, whom he called a “poet-painter,” a title he otherwise reserved for himself. Try looking at one of Cummings’s poems, the ones not meant to be read aloud—one imitating striptease, or a drunk still drinking, or the twirl of a snowflake, or even a grasshopper on the page—and then looking at the screen. See how it hops.

Amber Medland’s debut novel Wild Pets was published by Faber last year.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/0CJX3Ro

Comments

Post a Comment