Marc Hundley, whose portfolio of posters appears in the Review’s Summer issue, first moved to New York City in 1993 to model for Vogue with his twin brother, Ian. They were twenty-two and modeling was a means to an end—funding what Hundley calls their “club kid” lifestyle. As their final job in the industry, Marc and Ian walked Comme des Garçons runway shows in Paris and Tokyo alongside the supermodel Linda Evangelista, for a payout of two thousand dollars each. The two brothers then moved from Manhattan to the apartment in Williamsburg where Marc still lives. In the late nineties, he worked as a carpenter and still-life photographer, and then began making T-shirts and posters for his friends in the downtown club scene, which led him to an interest in text-based art. His prints and drawings often take the form of flyers that play with the associative potential of text and imagery. He still works across various disciplines including graphic design, carpentry, photography, and fine art.

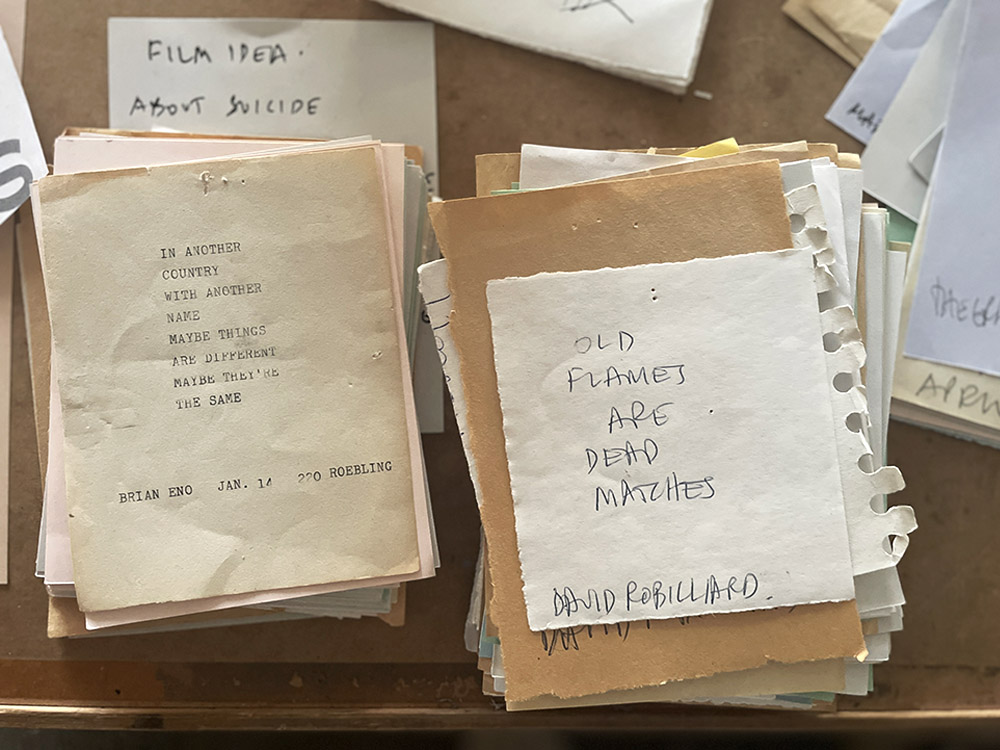

Hundley’s portfolio for the Review’s Summer issue constitutes something like a diary of several weeks he spent exploring the magazine’s archives this spring. The posters he created connect imagery and text in unexpected ways: each includes a particular phrase that caught his eye and pays homage to a work of art found in the same issue. (Four of these posters are now available to purchase in the Review’s online store.) In June, we sat down in his large studio in Bed-Stuy on chairs he had built. We shared a bottle of natural wine and talked about his work, the intimacy of being a twin, and how to write a love letter to a stranger.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever used your work to send somebody a love letter?

HUNDLEY

I have, and usually they’re love letters to people I don’t know. I once made a photocopied flyer that included a quote from a Magnetic Fields song—“While we’re still holding on, counting days until we’re gone, can we spend some time alone in our free love zone?” I added my address and the date, and I left part of it blank so that whoever picked it up could write in their own address. Another time I used an Arthur Russell quote—”I hope you need someone in your life, someone like me”—along with the date and place of one of my exhibition openings. I put romance into my work. Sometimes I think, I’m lonely, I’m single, I have no game—but then I realize that if there’s something I can’t say out loud to a person, I can use that. And I can be inspired by any kind of relationship. One of my pieces reads “It’s time that we began to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again,” from “So Long, Marianne” by Leonard Cohen. That was for my brother.

INTERVIEWER

You like making what you call takeaways—flyers, pamphlets, postcards. What appeals to you about this form?

HUNDLEY

When I first moved to New York and was learning about art, I was very influenced by House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home by Martha Rosler. She writes that art succeeds better in reproduction. Most of the work we know and love, we never see in its original form. I like takeaways because they’re not precious. I can give you something and you can throw it out or keep it. It’s almost like a book—you can either read it now or read it later, when you’re in a different headspace. It’s not like a piece that’s in an art gallery, where there are no seats and usually no bathroom—there’s not a lot of time for a piece to actually do its work on the viewer. The longer you get to live with a work, the better.

INTERVIEWER

How do you decide whether a work is going to be a painting or a book or a T-shirt?

HUNDLEY

I’m always writing down quotes from songs or books or poems, and always collecting images. When I’m about to make something out of them, I ask myself, Is this something I want to say to a lot of people? If it is, I might make a free takeaway—maybe something photocopied and cropped. If I want to say something loudly, I’ll make the piece big, and make only one of it. But if the thing I want to say is more subtle, which it usually is, I’ll make it something small.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned your brother, Ian. What’s it like being a twin?

HUNDLEY

I appreciate it more and more as I get older. We’ve always had a good and very close relationship. The first time we lived apart was when I was thirty-eight. I think being a twin can interfere with the need for another kind of intimate relationship, like with a partner—I’ve already got someone, so the need’s not there. He could say he hates me, that I’m disgusting, and I wouldn’t believe him. He’s still the person.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about putting together your portfolio for the Review. How did you approach the magazine’s archives?

HUNDLEY

The Paris Review project was about using one thing to say another. The archives were like a catalog. They gave me a dictionary to work from. It’s like what W. H. Auden says—if I was on a desert island, the book I would want is the dictionary, because it’s infinite. A novel is finite in how many ways you can read it, and the Paris Review archives contain so much—I thought, If I couldn’t say something out of what’s in these things, then I have nothing to say. I liked the idea that the posters would lead people back into the archives that had inspired me.

Na Kim is the art director of The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/ckhpt8q

Comments

Post a Comment