National Photo Company Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The seventies and eighties were a high point in American dance, and consequently, dance on television. As video technologies advanced, one-off performances inaccessible to most could be seamlessly captured and broadcast to the masses. Like all art forms, dance at this time was also influenced aesthetically by this new medium, as cinematic techniques permeated the choreographic (and vice versa). Today, many of these dance films are archived on YouTube. My favorite is a recording of avant-garde choreographer Blondell Cummings’s Chicken Soup, a one-woman monologue in dance that aired in 1988 on a TV program called Alive from Off Center. The piece is set to a minimalist score Cummings composed with Brian Eno and Meredith Monk. Over the music, a soft feminine voice narrates: “Coming through the open-window kitchen, all summer they drank iced coffee. With milk in it.” Cummings repeats a series of gestures: sipping coffee, threading a needle, and rocking a child. She glances with an exaggerated tilt of the head at an imaginary companion and mouths small talk—what Glenn Phillips of the Getty Museum calls her signature “facial choreography.” Her movements are sharp and distinct, creating the illusion that she is under a strobe light, or caught on slowly projected 35 mm film. She sways back and forth like a metronome, keeping time with her gestures.

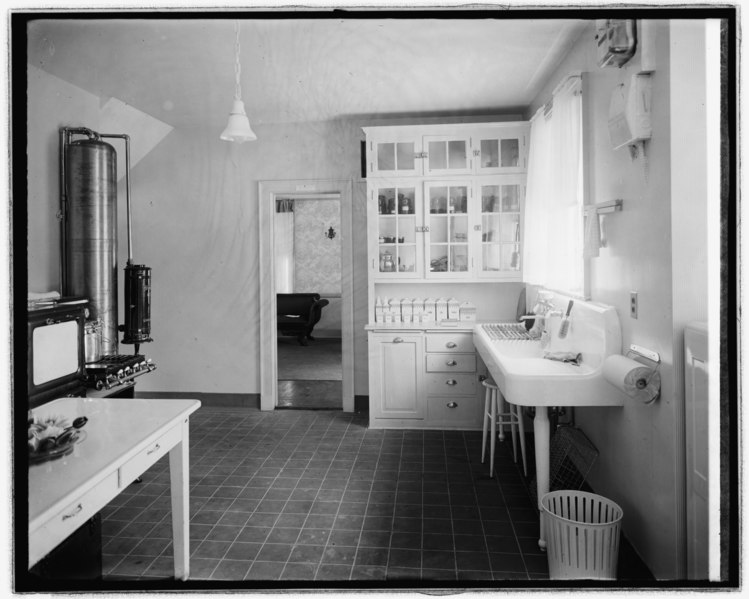

This particular performance placed Cummings in a detailed set evocative of a fifties household. But when she performed Chicken Soup onstage, accompanied solely by piano music, there was no set at all aside from a wooden chair. In this recording, for example, of a 1989 live performance at Jacob’s Pillow, her movements themselves seem endowed with greater importance, and the barrier between storyteller and audience feels gauze thin. Chicken Soup is an invitation inside, into a conversation that is both private and familiar. “They sat in their flower-print housedresses at the white enameled kitchen table,” the voiceover continues, “endlessly talking about childhood friends. Operations. And abortions.” The work premiered in 1973, the year the Supreme Court ruled on Roe vs. Wade, but Cummings’s kitchen could be any woman’s—anytime, anywhere.

—Elinor Hitt, reader

I was recently gifted a copy of Mary Gaitskill’s 2005 novel Veronica by a friend, with a warning: You might like this a bit too much. Indeed, I was immediately engrossed by Gaitskill’s narrator—the wistful, appearance-obsessed Alison—and her own habit of liking things a bit too much. The Alison of the novel’s bleak present, a feeble woman plagued by hepatitis, a codeine addiction, and a stiff arm, is preoccupied by her glamorous past, constantly revisiting the series of events that took her from Californian teenage runaway to Parisian fashion model, and ultimately ejected her into the glum world in which she finds herself several decades later. Now, every interaction in her daily life—from riding the bus to cleaning offices as a temp—hurtles Alison into a well of memories, reminding her of the porcelain-faced model she once was. In interviews, Gaitskill has described the book’s structure as “almost like a palimpsest, rather than flashbacks—it was one time bleeding through another. Sometimes I changed the time frame by decades in one paragraph or even in one sentence.” There’s a violence in the way the past mercilessly seeps into Alison’s life, soaks it, weighs her down. But she doesn’t see it that way: “I feel like the bright past is coming through the gray present,” she says hopefully, “and I want to look at it one more time.”

Alison’s vanity prevails even as her physical body decays, providing opportunities for shrewd, annihilating appraisals of the strangers she meets, descriptions which linger for a beat longer than you’d expect. “He’s got the face of someone who’s been beat too many times,” Alison notes of her neighbor Freddie. “He’s also got the face of somebody who, after the beating is done, gets up, says ‘Okay,’ and keeps trying to find something good to eat or drink or roll in.” Nearly every sentence of the book is profoundly energetic, with each darting line pushing up against the next in surprising ways: “I loved them like you love your hand or your liver,” she says of her parents, “without thinking about it or even being able to see it.”

—Camille Jacobson, business manager

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/p93iHmS

Comments

Post a Comment