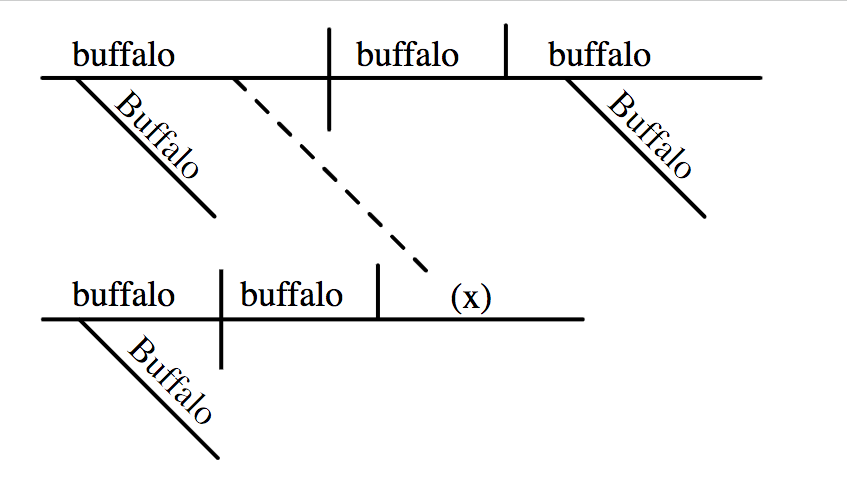

Sentence diagram of the sentence Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo. Craig Butz, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

From Stoner by John Williams:

And so he had his love affair.

And:

In his forty-third year William Stoner learned what others, much younger, had learned before him: that the person one loves at first is not the person one loves at last, and that love is not an end but a process through which one person attempts to know another.

These two sentences, pages apart, are both perfect. It should be obvious why, but perhaps they are more perfect because the first precedes the second, and the second is a kind of cracking open of the first or maybe a kind of blooming, grammatically and otherwise.

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

And more of our favorite lines from our recent reading:

From “The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick:

She only stood, because if she ran they would shoot, and if she tried to pick up the sticks of Magda’s body they would shoot, and if she let the wolf’s screech ascending now through the ladder of her skeleton break out, they would shoot; so she took Magda’s shawl and filled her own mouth with it, stuffed it in and stuffed it in, until she was swallowing up the wolf’s screech and tasting the cinnamon and almond depth of Magda’s saliva; and Rosa drank Magda’s shawl until it dried.

—Camille Jacobson, business manager

From Milkweed Smithereens by Bernadette Mayer, forthcoming November 2022:

the rain it raineth every day & it will never stop, this will be good for the tomatoes, just above the bird feeder is blue sky, now thunder, no rainbows though

—David Wallace, advisory editor

I enjoyed many of the sentences in Amy Larocca’s profile of Kaitlin Phillips, but this was my favorite:

“So much of press is like, they teach you safe press,” Ms. Phillips said. “I’m incredibly into, like, edging.”

—Emily Stokes, editor

From Maps of Our Spectacular Bodies by Maddie Mortimer:

There are thick layers of filth coating her once-white feathers; the soot and dust and debris gathered over years of rare exchanges and scratchy landline calls made far too late; she stinks with it, shrinks in it, can’t rid her lead-grey life of it, and I feel quite encouraged, quite invigorated by this one, as she puffs her chest out and makes a few snide comments about a time when life was pure, before regret and penance and me.

—Clarissa Fragoso Pinheiro, intern

From “On the Island” by Gerald Stern, in Lucky Life:

I like to think of floating again in my first home,

still remembering the warm rock

and its slow destruction,

still remembering the first conversion to blood

and the forcing of the sea into those cramped vessels.

—Owen Park, reader

From Earth Keeper: Reflections on the American Land by N. Scott Momaday:

She has gone to the farther camps, but her bones are at home in the dress, in the earth.

—Jane Breakell, development director

From Youth by Tove Ditlevsen:

Childhood is dark and it’s always moaning like a little animal that’s locked in a cellar and forgotten.

—Campbell Campbell, intern

From Untitled (1–5) by Nazareth Hassan:

sounds of crusts falling

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/7daCNYi

Comments

Post a Comment