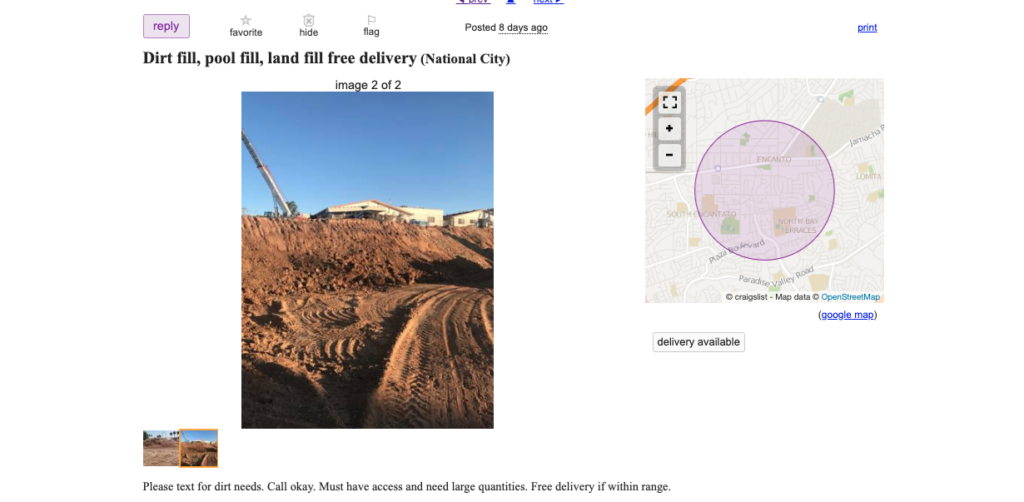

For the past three years, I’ve filled a folder on my desktop with pictures of dirt that I found on Craigslist. The dirt in each picture was offered free of charge to whoever was willing to pick it up (“You haul”) or, if you were lucky, a free-dirter might have offered free delivery. Depending on the angle and composition of the images, “free dirt” posts on Craigslist can look like unintentional landscape vistas. Some shots feature calloused hands covered in tawny fill dirt, vignetted by palm trees and paved driveways in postwar cul-de-sacs. There are endless frames of earth spilling onto asphalt, flattened mounds of rich brown soil indented with tire tracks, craggy piles of dirt gathered evenly along the perimeters of blue tarp in driveways. Where I’m from, in Southern California, free dirt is abundant.

Dirt moves and circulates as part of its role in the man-made ecosystem of building, demolishing, and rebuilding. But there’s a paradox: the more that dirt is touched and handled by human hands, the more expensive it becomes to move around. If you bring “non-native” soil to a construction project, you are subject to costly soils testing. When a project has tight specifications—public libraries, for instance, have highly regulated dimensions and measurements—leftover dirt becomes surplus material. And you can’t simply throw it out. Disposing of dirt in Southern California is a long, bureaucratic process, one San Diego landscaper told me; one must apply for a permit to dump excess dirt and must transport it in a vehicle of a particular class. Some construction companies have even turned to posting their excess soil inventories online via dirt-matching sites. (“Connecting people who have dirt with people who need dirt,” reads the ad copy on DirtMatch.com. They boast 5,914 matches in the last ninety days.) For the homeowner who just wants to build up the ground around their new in-ground pool or the young couple working on the raised beds in their vegetable garden, all of this is expensive and time-consuming. And so they turn to Craigslist, and to the world of free dirt.

The language in these online ads is friendly; the soil identification is anecdotal. “Fill,” or nutrient-poor excess dirt, is most abundant and available online because it’s surfeit junk—the petty cash of land use. “This was dug up from our backyard when redoing our lawn,” reads a recent post from Rancho Bernardo, alongside a photo of a medium-size pile of brown dirt and the neon-green handle of a shovel. “I don’t have a truck so you will have to pick up but I can give a helping hand to load the dirt.” It’s nothing fancy, even in the world of dirt.

Still, these photos fascinate me, in part for their strange resonances. In my folder and out of context, free-dirt photos can come to look strangely like Ansel Adams photographs; the sunlight hits Martin from Pasadena’s project scraps the way it might strike the Half Dome in Yosemite. Dirt piles at a construction site at an East County community college, captured at high noon, can look, oddly, like a mountain range shot in deep contrast. Scale is erased. Shadows deepen the sense of something like the sublime.

But free-dirt photos, unlike most images of monumental landscapes, are evidence of people’s bodily relationship with the land: the shadow silhouette, the calloused hands, the traces of human labor punctuated by the presence of tools coated in dust next to the green coil of a garden hose; the hint of a paved sidewalk in the corner frame, a picket fence, or a half-cameo profile of a worker, maybe somebody’s uncle, in a black cap and a pair of Carhartts. In one photo I see, in his own backyard in Tarzana, a city surveyor turned amateur landscape photographer: in the background there are the black asphalt and the manicured sidewalks of tract housing, and a residential-size recycling bin frames two conical scoops of dirt, one darker than the other—and in the foreground, nearly centered, is the shadow of a figure holding the basic square of a smartphone above their head to get the most comprehensive perspective. This reminds me, strangely, of a 1939 photograph of a levee, taken by a geological engineer, which features the silhouette of the surveyor hired by the construction company, backlit by the sun as he documents both the site and his own portrait.

The inside of the Cajalco Reservoir, with a ninety-foot levee. Riverside, November 19, 1939. Photograph courtesy of the University of Southern California Libraries and the California Historical Society. Digitally reproduced by the USC Digital Library.

Pictures like this—both formal landscape imagery and images from the geological survey—were used as propaganda to build a global understanding of American “public land” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. U.S. Geological Survey teams organized, designated, and measured borders and territory boundaries, cataloguing the land in photographs that document the overarching aesthetics of what is now considered the mythic American West. “Photography was not only crucial in fostering a consciousness of conservation of public lands,” writes Ana Cecilia Alvarez for Real Life, “but it also determined how these exceptional places were framed and consumed.” Curator Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell writes that “two types of landscape photographs [were] circulating in Washington, D.C.,” in the 1860s: “the horrific pictures of Civil War battlefields” and sumptuous C-prints of Yosemite Valley.

Mountains being moved in Lopez Canyon, April 22, 1957. Photograph courtesy of the University of Southern California Libraries and the California Historical Society. Digitally reproduced by the USC Digital Library.

There is a way to read free-dirt photographs as contemporary, accidental, sideways takes on these classic American myths. On Craigslist, they point to places where dirt and aspiration combine toward the development of yet another private dream, owned or rented, summarized by its weight in piles of soil. Build a yard or raised garden bed with a neighbor’s dirt. This swap meet of the commons is the American Dream made surplus. Picture hills of leftover construction fill in the cul-de-sacs of tract housing or a half-built house erected only to blight itself with its own materials: sacks of soil, slumped on the perimeter of an unrealized yard. These, too, are American monuments.

Recently, I caught my mother singing through her kitchen, carrying a bag of dirt in her arms. “They gave me the good dirt,” she said. The landscapers had given it to her off their truck, for free.

Angella D’Avignon is a writer in California.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/6BwNEiR

Comments

Post a Comment