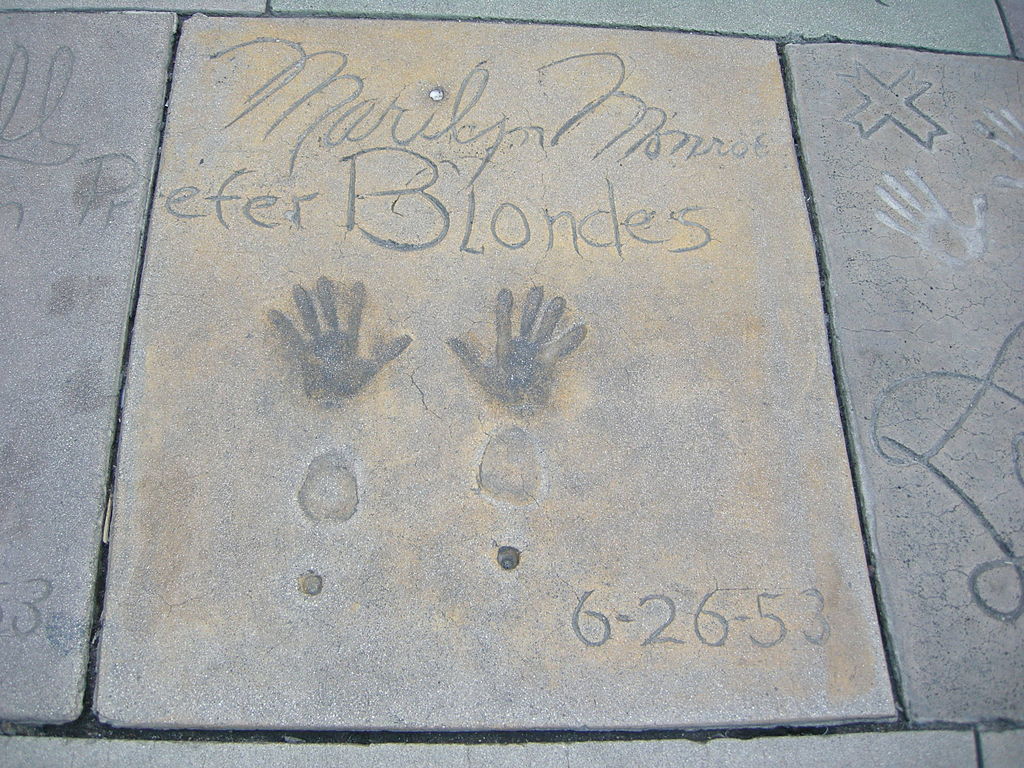

Marilyn Monroe’s hand and footprints outside the Chinese Theater in Hollywood. Photo by Sailko, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0,

This week, we bring you recommendations from three of our issue no. 241 contributors.

Twenty-two years late I picked up Blonde, Joyce Carol Oates’s enormous novel about Marilyn Monroe. At first it jolted me with its jangling, sick vulgarity. My pulse rate shot up. I was trembling. I wanted to throw it across the room. But I also had to acknowledge immediately that it was brilliant. Three days later I dragged myself out the other end, shaken by a sort of angst and awestruck by Oates’s manic power, her huge imagination, her ability to command great cataracts of material—to convey a soul mortally wounded in childhood, laboring in its squalor to recreate itself.

—Helen Garner, interviewed in “The Art of Fiction No. 255”

I first read Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude in my family’s summer cottage on Doolittle Lake in Norfolk, Connecticut: an A-frame constructed in the thirties as an afternoon teahouse, with beautiful interior wooden beams and an immense rock slab capping the chimney. An occasional mouse, of course, would seek shelter in the loft spaces, but that August I started to hear a constant grinding noise at night that was not very mouselike. I tried to determine the source of this pesky sound, with no luck. Then one day, as I was completely locked into the last few pages of Márquez’s book—when “all the ants in the world” are “dragging toward their holes” the “dry and bloated bag of skin” of a dead baby with the tail of a pig—the heavens broke open inside our cabin. A panel of insulation had collapsed from the weight of sawdust created by a colony of carpenter ants gnawing into the rafters. I jumped up from my chair in shock and terror, madly brushing them off, gasping from the physical and emotional reality of the end of One Hundred Years of Solitude—this was magical realism at its best.

—Keith Hollaman, author of “Dark Suit and Bow Tie”

Three-part insomnia: I awake at 4 A.M. with a divided mind anchored to the word snake. How it is the perfect representation for the reptile it embodies—starting with the apprising sibilant, then quickly moving off the page by way of a speedy quartet of letters. A lightning-strike piece of diction. Like calling out fire in a crowded space. But while snake is an auditory slither, fire is a fist. That is the first of my early morning’s non sequiturs.

Then I think about my current reread of The Age of Innocence, a nearly perfect novel (Wharton is a kinder, American Flaubert), and of the canniness of Wharton’s depiction of May, who is the true archer, the personage of the bull’s-eye and the off-stage orchestrator of her novel. I find it challenging to understand why Newland Archer doesn’t climb the five flights of stairs to Ellen’s apartment, where he would have found the woman of his true passion—and handily displaced the Frenchman. It’s worth reading the last chapter again for the subtleties planted there: “Perhaps she too had kept her memory of him as something apart; but if she had, it must have been like a relic in a small dim chapel, where there was not time to pray every day.”

And before rising for the day, as the rising sun, I let the memory of Wu Tianming’s 1996 movie The King of Masks come back into focus. I see the many faces of a man who, at the end of his life, wants a grandson to continue the art of mask opera and ends up with something equally beautiful that he could not have imagined, in whatever guise. I might have been dreaming of my daughter earlier. I might have allowed the avatars of the imagination and the past to form a portal, a foothold, a path forward into the new day …

—Daniel Halpern, author of “Mating Tango”

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/CJsl9Tc

Comments

Post a Comment