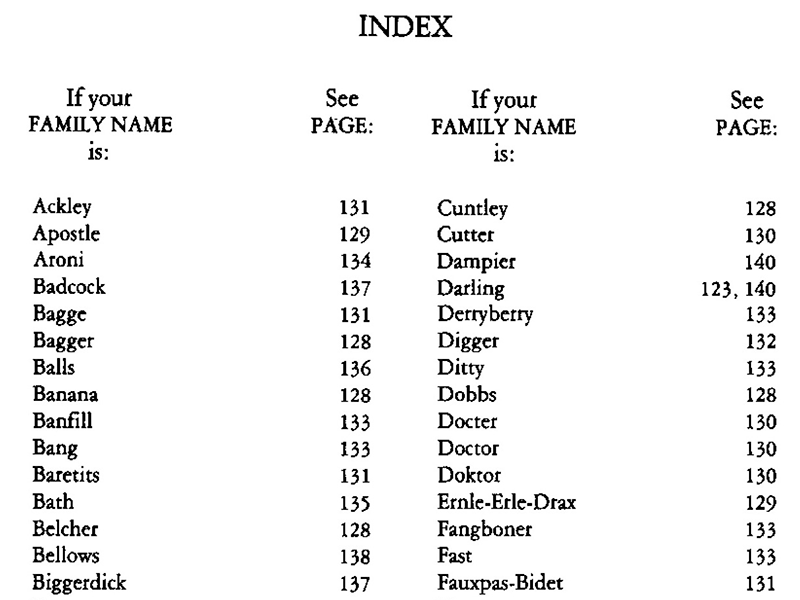

A page from “How to Name Your Baby,” in issue no. 66.

John Train, a cofounder of The Paris Review and its first managing editor—or “so-called managing editor,” as he often put it—died last month, at age ninety-four. It was Train who coined the Review’s name and, in its early days in Paris, as a member of the Café Tournon crowd, he pushed the magazine away from criticism, writing later that “theories, both literary and political, are the enemy of art.”

Train went on to become “an operator in high finance and world affairs,” as the Times obituary put it today, but many will remember him best for his love of small idiosyncrasies: in the early fifties, while studying for a master’s degree at Harvard in comparative literature, Train noticed in Collier’s magazine a Mr. Katz Meow, which led to an earnest obsession with collecting what he called “remarkable names of real people.” You can find some of these in our Summer 1976 issue, no. 66, which features a fourteen-page list of names Train had unearthed in the records of a very real and now-defunct state department called the Office of Nomenclature Stabilization. (We published an appreciation of “How to Name Your Baby” online in 2015.) Train announced his departure from his post as managing editor, as George Plimpton and Norman Mailer recall, with singularly dry humor:

One day in 1954, after a year of organizing things in the office, he left a note in his In-box stating, “Do not put anything in this box.” By this he meant to tell the rest of the staff that he was moving on to something else.

From the Chelsea office, the staff of the Review are thinking of Train, his legacy and “In-box,” his family and friends. He will be missed.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/DGWFykI

Comments

Post a Comment