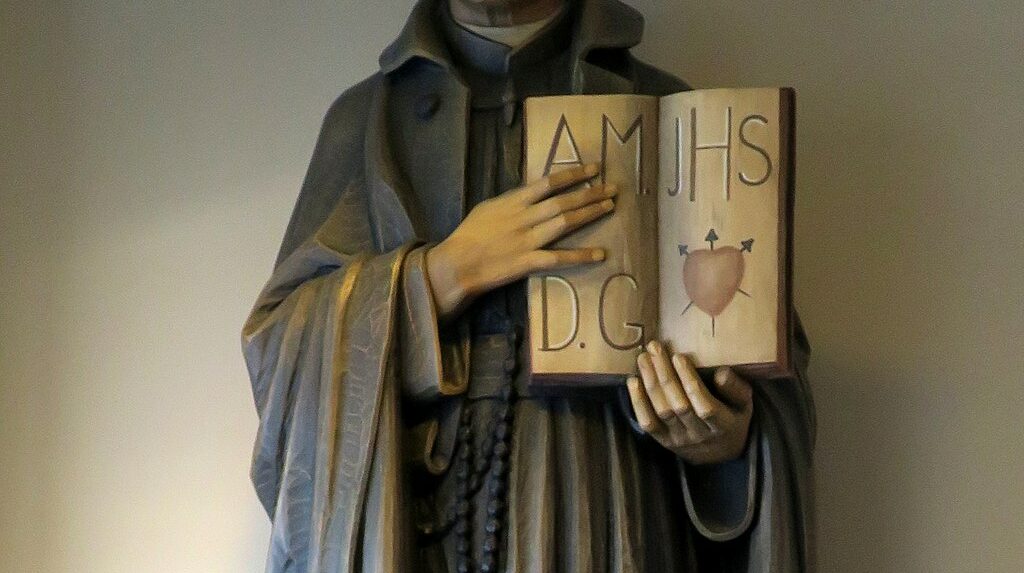

Saint Ignatius of Loyola Church in Cincinnati, Ohio. Photograph by Nheyob, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

In my hometown of New Orleans, which is overwhelmingly Catholic, certain men I know go periodically to a Catholic retreat up the river. They go there to repent. Probably they contemplate goodness. And goodness is a lot more interesting than it sounds.

The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius of Loyola are used as the format for these pursuits. Saint Ignatius of Loyola was a womanizer, purportedly—like a lot of the saints. So probably he wanted to repent, too.

My friends growing up in New Orleans were all Catholic girls, and I’ve often wondered about their Catholic qualities. They seem to have less vinegar in their veins than Jewish girls (like me). It fascinates me to delineate the character traits informed by their religion. I’m drawn to its organized tenets. I’d read the Catholic catechism just for kicks.

But you don’t have to be Catholic to appreciate Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises. They are a set of prayers and practices divided into tantalizing rubrics such as Three Classes of Men, Three Kinds of Humility, Rules for the Discernment of Spirits, Daily Examination of Conscience, etc. Their goals are constructive: to overcome disordered inclinations; to seek indifference and humility; to elicit courage, discipline, and perseverance. Just take Jesus out of it and there you go. I took Jesus out of all those phrases, which would otherwise include the strange concept that you’re doing all this for his sake—rather than for your own sake, just to be more worthy. I don’t know why you need Jesus to aspire to this quest. So it’s not like I’m some sort of religious maniac.

The Spiritual Exercises can get a little weird, though they still speak to me: you’re supposed to ask for shame and confusion. So if you feel shame and confusion, don’t worry, you’re on the right track! Because it’s about remorse—when you know you are bad, it is good. It is half the battle won.

I also revel in The Palace Papers by Tina Brown, with its effortless intelligence and command of a wide array of royal facts and concepts, even when at the end Brown suddenly descends into bathos about Queen Elizabeth, as people sometimes tend to do.

But I read that book before the queen’s death, so I must now add prescience to Brown’s powers of discernment—the emotional conclusion, the sudden eulogy—though I guess you didn’t have to be a genius to realize the queen was on her last legs. She seemed immortal, though. Like one’s mother, sort of.

A few days before she died, I had bought the latest issue of Tatler, which was entirely devoted to the queen, with quaint, sepia-tinted photos telling her life story, etc. I kept thinking, Why did I buy this, and/or, Do I have to keep reading this. But something kept me from throwing it away, for which, afterward, I was glad.

Nancy Lemann is the author of “Diary of Remorse,” published in issue no. 241 of the Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/WYkyDPB

Comments

Post a Comment