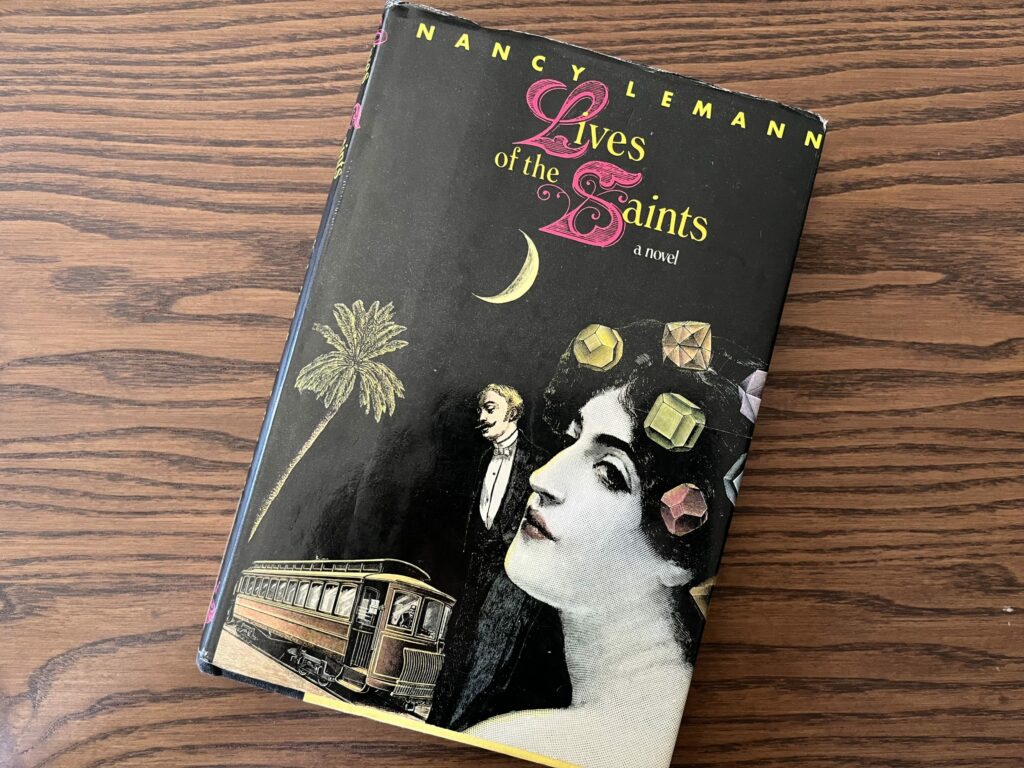

In our new Fall issue, no. 241, we published Nancy Lemann’s “Diary of Remorse.” To mark the occasion, we asked writers to reflect on Lemann’s remarkable literary career.

I picked up Nancy Lemann’s Lives of the Saints from a sidewalk pile in Greenpoint in October 2020, just a few minutes before it started raining in sheets. I read the novel in one sitting when I got home. The next day, I lent it to a friend with whom I was crashing for a few weeks. She returned it twenty-two months later, at the beach. Before we even left Fort Tilden I found myself lending it out to another friend. I’m not very generous with books, to be honest, but for some reason, this novel, like an early-aughts chain email, demands to be forwarded. It is a short book, which makes it a good loan to a friend, because you can jointly anticipate a sense of accomplishment. And it may then become a field guide to certain shared experiences of Youth—allowing you both to observe, for instance, on a summer night when everyone around you is having Breakdowns, that this is exactly like Lives of the Saints.

Why had I read it in one afternoon, though? I remembered feeling warm, somehow, like I’d been drinking hot chocolate; that was something I also hoped to pass on to my friends. But I’d forgotten precisely how the sensation arose out of the book’s setting: decadent, upper-crust New Orleans, where desultory people young and old drink heroic quantities of gin, embark on doomed marriages and affairs, and generally go to seed. As I revisited my (second) copy of Lives of the Saints, I realized what appealed to me so much, then and now, was the portrait of the thick, interdependent, entangled community within which these eccentrics thrive. The virtues and morals of this Southern hothouse are as lucid as those of Jane Austen’s or George Eliot’s provincial outposts. We learn that Claude, the narrator’s clumsy love interest, is not only “kind” and “honorable” but also likes people more the longer he has known them. (Thus, reasons the narrator, she will always have an “edge” on his affections.) Would that we had such a firm theory of every character in our own lives—and their extended families, too! The narrator also knows that Claude’s father has been eating a dozen oysters “at noon in The Pearl” every day for four decades—and that Claude’s great-great-grandfather came to Louisiana from Germany in 1836. The verb tenses that scaffold this fictional world indicate reliable recurrences of a dim, shared past in a nostalgia-soaked present: one aging grandee “always quotes from” a dreaded verse history of the Civil War, and a senescent debutante trots out “the story of the Countless Offers.” And then there’s the bracingly intimate “we,” as in: “We used to hear Henry Laines scream at his girl friends … in the apartment across the garden at night from his house.” And so do we, for the hours we spend in this book.

The aimless narrator’s return to New Orleans after her four years at a northeastern college is a clever device with which to reconstruct this milieu for us outsiders. It is not a world you long to join or one whose passing you lament—a world where Black people serve white “wastrel youth,” where parties are staged unselfconsciously at plantations, where a typical setting of a scene includes “everyone screaming for the black maids, with vivid colors of black maids in white uniforms on the velvet green lawn.” These characters inhabit less a stratum than a caste—one that you can’t help but feel deserved the same ultimate Breakdown as most of its members. But to thread the needle so deftly on such people is the supreme achievement of the novel’s voice: deadpan, hilarious, histrionic, anthropological, fatalistic. Some of the narrator’s lines have rattled around my head for the past two years, like: “I could only love one person. This was my innate principle.” She does not write this off—unlike other sentiments of her youth—with her backward glance, and that seemed, and seems, important to me. Many of us cling to similar credos that can appear, especially in what the narrator might call the cold Yankee North, like relics of a bygone era, but maybe we don’t have to let them go. At least, that’s how I felt rereading this novel, as I once again underlined words I had long ago committed to memory: “I cannot just transfer my affections, for they are carved in stone.”

Krithika Varagur is the author of The Call: Inside the Global Saudi Religious Project and an editor of The Drift.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/WMZUnTo

Comments

Post a Comment