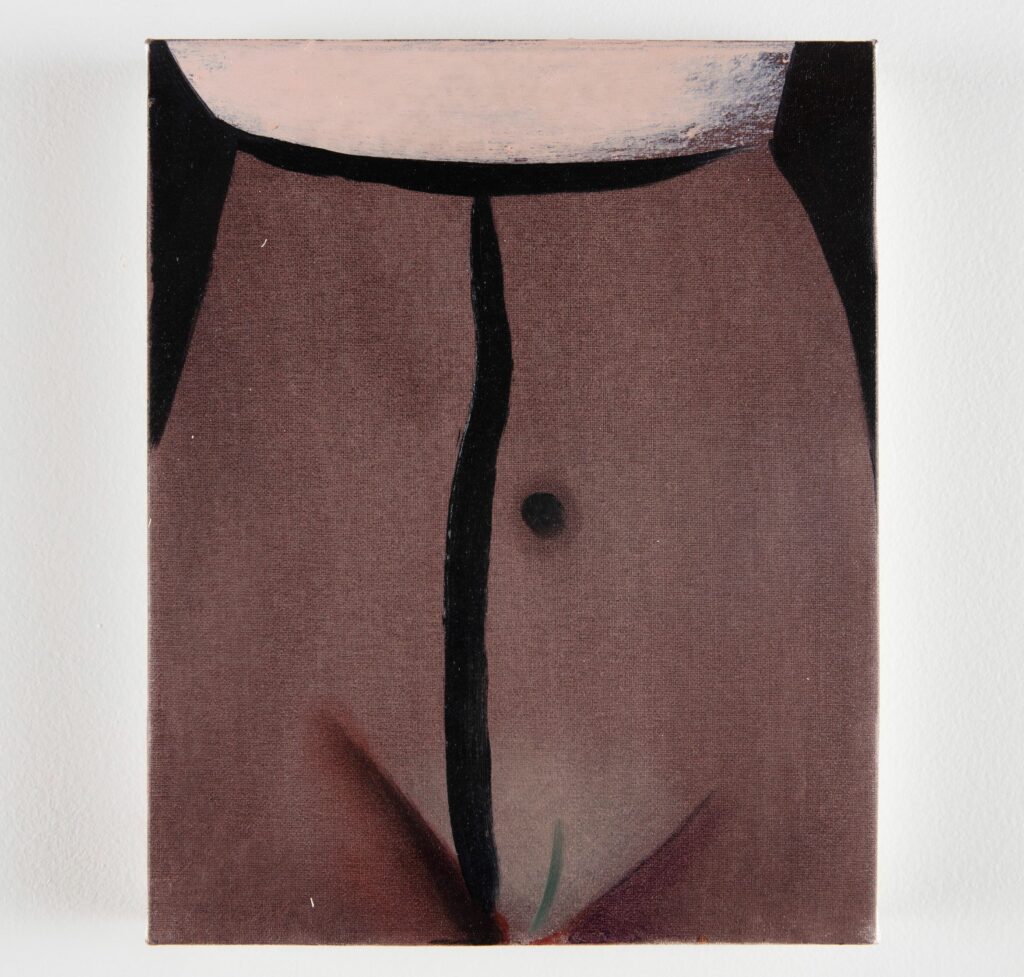

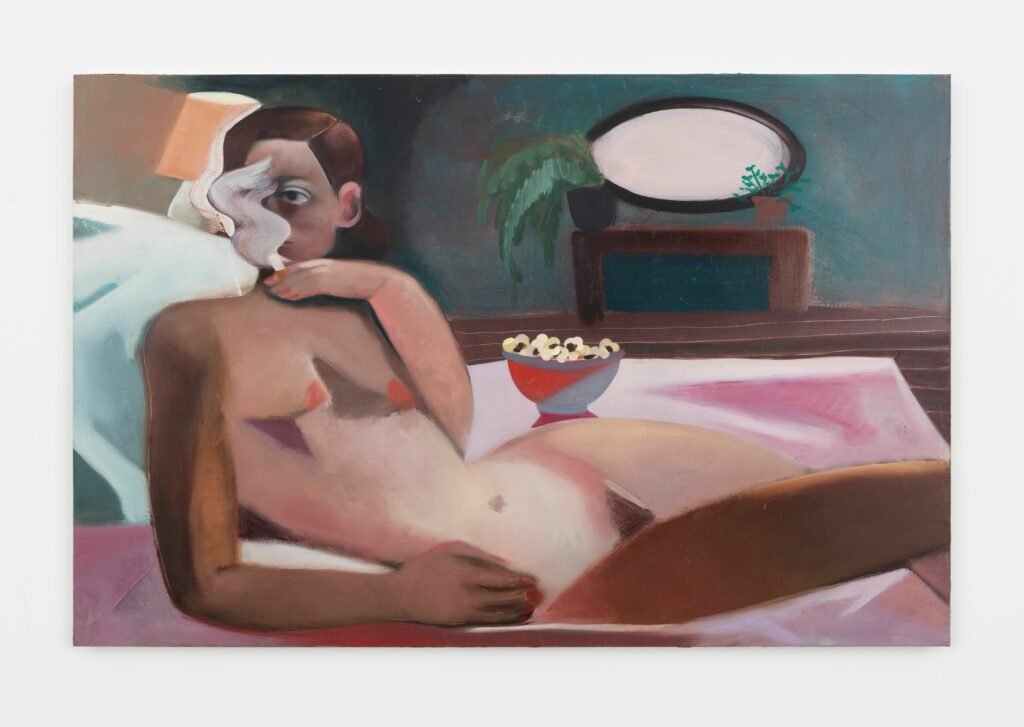

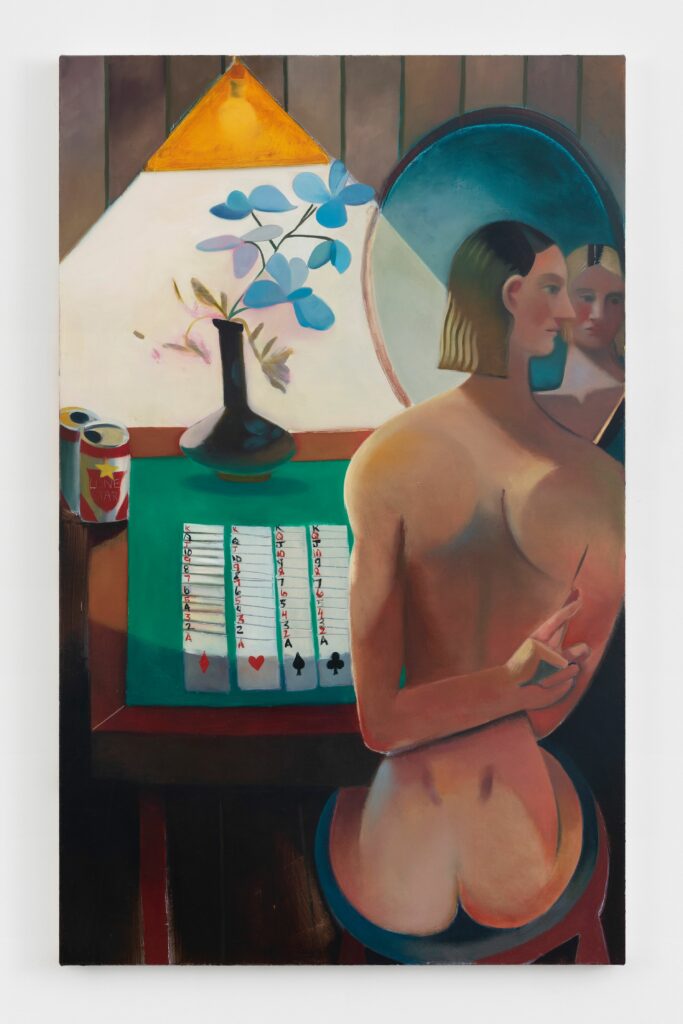

The women in Danielle Orchard’s paintings are usually undressed, or only partially clothed. They might be smoking a cigarette in the bath, or staring at themselves in a mirror, or eating from a bowl of popcorn in bed. Orchard’s settings are often mundane—a bedroom, a boudoir, a kitchen—but these environments are striking in their angularity and irregular perspectives, the paintings’ compositions at once calling to mind the art historical tradition of the female nude and unsettling it. Her painting Lint graces the cover of the Fall issue of the Review and depicts a woman in stockings and no knickers. We talked about Balthus, working with life models, outsize objects, how she made Lint, and the notable absence of pubic hair from the painting.

INTERVIEWER

When did you start gravitating toward the female nude?

ORCHARD

The painting program I was in at Indiana University was fairly traditional and very observation-based, and the nude was a learning tool and a formal device: a way to develop the ability to depict volume and line. When I arrived at Hunter College in New York for graduate school, I didn’t want to abandon the nude, but I started to wonder, Who are these women? What is this uncanniness to their nudity? And who am I, as a painter, in this setting? I realized that the nudes I was painting were amalgams of my own experiences, but they were also deeply familiar images from art history. I was identifying with these characters and thinking about how their bodies might mirror my own, or how I might be unintentionally mirroring them. And so I started building a visual language with the female nude at the center.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have particular influences, or anti-influences, in painting female bodies?

ORCHARD

Everyone on my bookshelf is an artist I truly love and look to for inspiration—and whom I steal from directly. I think a lot about Picasso, naturally, but I’m also really into Balthus. The construction of his paintings—the eeriness and the function of light—were important to me when I was learning how to paint. Back then, the content of his paintings was never questioned by me or by my professors.

INTERVIEWER

How did you come to question it?

ORCHARD

When I got to New York, I saw a Balthus painting in person for the first time—Thérèse Dreaming at the Met. The professors of mine who’d come out of a feminist tradition often said it was incredibly fucked up in terms of its depiction of this sexualized adolescent, and would ask me to question my relationship to it. And I did question it—but I also sometimes felt like asking, Why? It’s such a great painting! I ended up making a couple versions of a painting inspired by Thérèse Dreaming. In Balthus’s original, there’s a cat lapping milk and it’s a pretty erotic little euphemism. I thought it would be funny to make Thérèse into a cat lady: an adult woman, a spinster, surrounded by cats.

INTERVIEWER

How do you see your work in relation to the art historical tradition of nudes?

ORCHARD

Of course, once you learn about the subjugation some women have experienced at the hands of certain male artists who were depicting them, you can’t help sympathizing with their experiences as models. With this newer body of work, I’ve been trying to complicate things—to make my paintings at once more humorous and more specific to a feminine experience. The cover for The Paris Review is a good example. The idea of the painting was to show the discomfort of wearing tights. If you’ve spent a day walking around in tights, you’ll know that tights are always a bit less sexy than you’d intended. They have this formal function, which is to create clean lines on the body, but the internal experience is quite different. The seam is always off-center.

INTERVIEWER

How did that painting come to you?

ORCHARD

I had started to include pieces of clothing in my paintings—clothing that I felt was somehow more revealing than nudity itself. The transparency of tights interested me and posed a new painting problem, one I hadn’t taken on before.

INTERVIEWER

Why tights and no knickers?

ORCHARD

I thought it would make her appear even more uncomfortable. It would heighten the sensuality, but also, anyone who has ever worn tights would just be thinking about how gross that would feel. I was interested in these little gestures—nods in the direction of a woman’s true experience—which are often lost on a male viewership. In my experience, male viewers tend to see the painting in sexualized terms, while the humor is almost always picked up on by female viewers.

INTERVIEWER

And why no pubic hair?

ORCHARD

To make it a little bit more garish. And also just to continue the line—to underscore the linearity of the image. I’ve done other versions where she has a huge bush, but this image seems to me to suggest something about this character—maybe how meticulous she is, or that she wants to be seen as manicured. And then, of course, she’s having this wardrobe malfunction.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me a little bit about the process of making this painting—the materials you used and the iterations of the work.

ORCHARD

I worked hard to find this perfect temperature of brown for the tights. I tried so many different ways of layering, to different effects. A lot of them turned out pretty beautifully in studies, but then I couldn’t translate them onto a larger canvas. I couldn’t get it to feel quite right. This painting was probably the last one I did in preparation for a larger painting in the show that’s up right now at Perrotin in Paris. The brown was actually just an underpainting—some sort of residue from my palette table. I was about to scrape it off and then I realized that it was precisely the temperature I had been after. I’ve been trying to reproduce it, trying every brown I have in the studio, and it’s never coming back.

INTERVIEWER

The colors in this painting are darker than in some of the works of yours I’ve seen. Why is that?

ORCHARD

I had been trying to land on a color that felt like wearing stockings. At the same time, I realized afterward, I’d been looking at a lot of work by Georges de La Tour, who painted these dark, very calm religious paintings that are very angular and strange, in earthy colors. They have a lot of chiaroscuro, and what’s illuminated are the expressions of the women.

INTERVIEWER

How long did it take to paint this one?

ORCHARD

It took ten minutes to make that painting. Although that’s not exactly true, because of the time spent rehearsing on other canvases. I think about this all the time: how with runners, for instance, a single sprint is the accumulation of all the effort that went in before the actual race.

INTERVIEWER

Do you work with life models now, or from memory?

ORCHARD

After Hunter College, I couldn’t afford models, so I started pulling from old sketches and from my memory and imagination. The anatomical irregularities I’m interested in often come from misremembering anatomy—from having a foundation but then getting it wrong. I like it when the misremembering seems informed by the experience of physically inhabiting a female body. I’ve noticed that if I’ve done push-ups that week, say, then the women in the paintings will get a little bulkier.

INTERVIEWER

You often paint groups of women together. A few times you’ve called them “characters.” Are they separate individuals, or are they you—or amalgams of the two?

ORCHARD

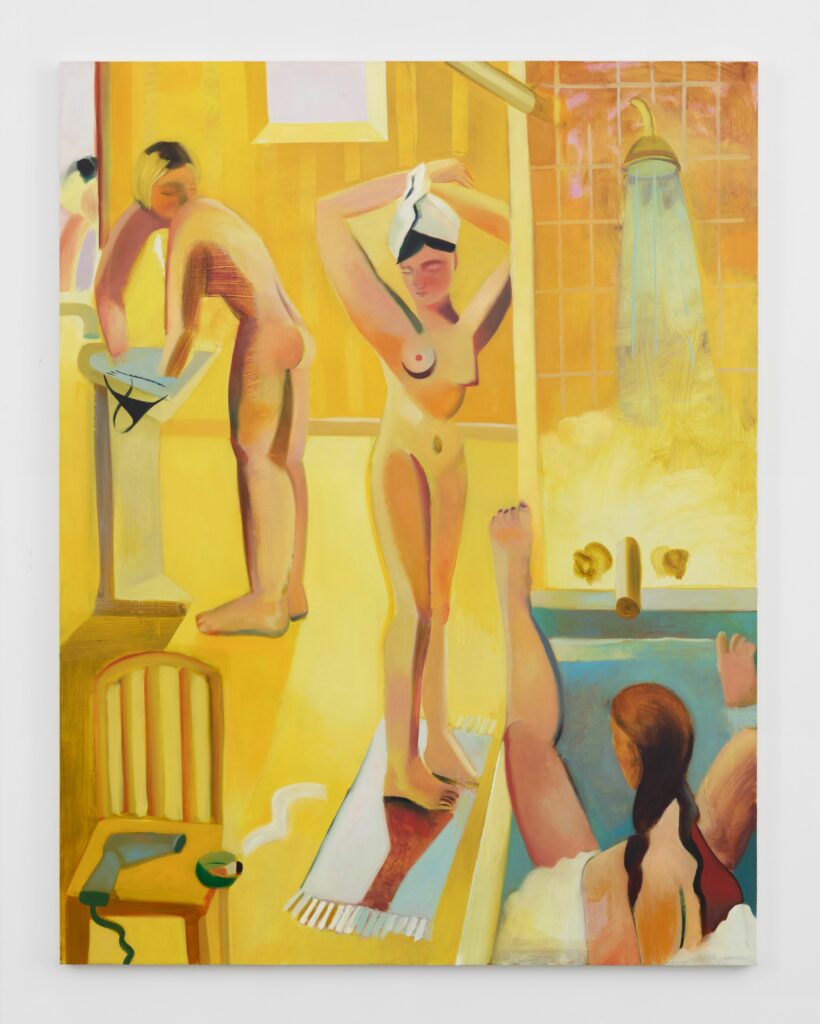

They’re certainly amalgams, but together they also function almost like an organism—a fungus or something like that. It’s like when you’re around a lot of other women and this incredibly dynamic experience of viewership takes place, where you’re looking at one another with empathy, certainly, but also with some critical edge, and you’re also thinking about yourself and how you’re being perceived.

Sometimes I include the same woman at different points in time in the same painting, as if she’s moved. There’s one painting I’m thinking of, a yellow bathroom scene that’s up right now in Paris, that has three figures in it, each at one step in the process you go through when you’re getting ready for an event: washing the hair, shaving the legs, putting on the makeup. A linear narrative stretched out visually.

INTERVIEWER

There are certain ordinary things that often recur in your paintings—nail polish and beer and pencils—and seem to play a kind of outsize role. Where do these objects come from?

ORCHARD

I think of them as outsize as well. I’m interested in the most generic version of all of these things. A phone is always a rotary phone, for instance, and a wineglass has almost emoji-level recognition and immediacy. I’ve noticed recently that these objects do often relate to a painterly impulse. The makeup and the nail polish are cognates to materials in the studio, and they’re symbols for navigating the ambivalence around how women are constantly reconstructing ourselves—like, almost every morning. Or I am, anyway.

Sophie Haigney is the web editor at The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/lEtY7Lm

Comments

Post a Comment