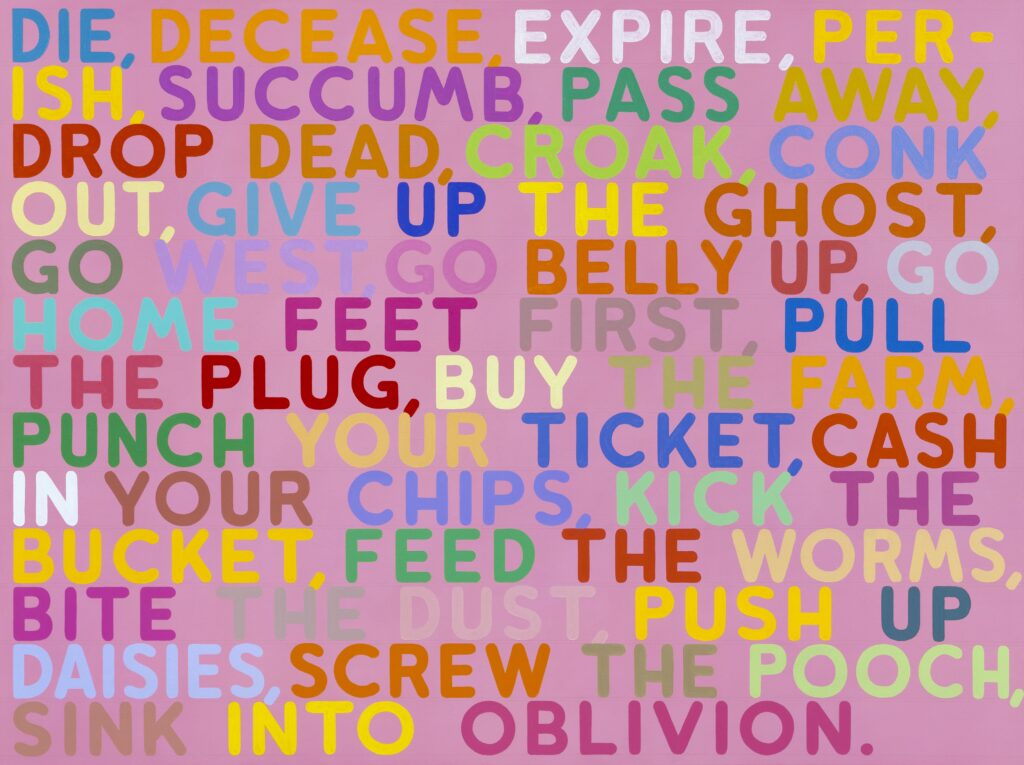

Mel Bochner, Bochner, Die, 2004, acrylic and oil on canvas, 60 x 80″. Courtesy of the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc., New York.

I have had a few of Mel Bochner’s slogans stuck in my head ever since I visited Peter Freeman Gallery to see a exhibition of his work, Seldom or Never Seen 2004–2022. Bochner—a conceptual artist known for his colorful, text-based paintings—first rose to prominence with a 1966 show called Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art. How good a title is that? (The show included a fabricator’s bill from Donald Judd.) The same cheeky spirit inflects his retrospective at Peter Freeman. Most of the works are text-based, brightly colored, and employ a cartoonish Comic Sans–esque font. In one, against a bubblegum-pink background (pictured above), he spells out clichés for death, which get more and more Looney Tunes as they go on: “Die, decease, expire … give up the ghost, go west, go belly up … screw the pooch, sink into oblivion.” On other canvases, the text is literally filler—white melting into blue, with the words blah, blah, blah dripping into nonsense. Bochner is playing with language, having a way with words, flickering between the register of the cliché and all the possibilities clichés can offer. It’s all a lot of fun. My very favorites are a canvas with writing so thin and light it appears to be in pencil, and one on which is written the perfect joke-warning, which I have since passed along to others: “Don’t make me laugh.”

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

Recently, after once again experiencing the bad behavior of a man—boring in the nature of its badness though nevertheless dispiriting—I once again turned to Take Care of Yourself, by the French artist Sophie Calle. The work was first exhibited as a multiroom installation at the 2007 Venice Biennale that incorporated photos, paintings, drawings, video, audio, and text. The project began when Calle received a breakup email from a man anonymized in the work as “X,” with the titular sign-off. “It was almost as if [the email] hadn’t been meant for me,” Calle wrote. So she shared the email with 106 women (107 participants, if you include a parrot who clawed apart a printed copy of the email), enlisting them in an endeavor reminiscent of a group chat’s collaborative evisceration and consolation in response to such situations. She asked that the women “analyze it, comment on it, dance it, sing it. Dissect it. Exhaust it. Understand it for me. Answer for me.”

And they did, using their skills as, among other things, tarot readers, Talmudic exegetes, psychiatrists, puppeteers, clowns, anthropologists, cartoonists, magicians, ikebana masters, mothers (such as Calle’s own), et cetera. An editor critiques the email’s convoluted syntax and obfuscatory language, which frames the man as a victim of his own nature and of Calle’s prohibition of infidelity. A lawyer analyzes it as a broken contract. A diva sings it as an aria. A poet reconfigures its language. The collection of responses is a masterpiece of women not only talking back but transforming what they’re talking to. It’s hilarious, over-the-top, and magical.

Take Care of Yourself was also published as a (glossy, pink) book. I received it from a man who said, not entirely approvingly, “This seems like something you would do.” I hope so. Calle wrenches the story away from the man who breaks up with her—and away from the randomness of event itself. Life becomes a story she’s telling, not just something she’s living through.

The man who signed off “prenez soin de vous” is Grégoire Bouillier, writer of The Mystery Guest, a memoir about being invited to a stranger’s birthday party by a woman who had broken his heart. This stranger was Sophie Calle. Later, he told The Brooklyn Rail that Calle “believes in the genius of the artist while I pay attention to the genius of life.” She wants to control, he implies, while he wants to observe. But if life sometimes behaves like a novel, why not start trying to write life for yourself?

By the end—of the text thread, the exhibition, the book—the impression left is not of messy sentences or tortured narcissism, but of creative bounty and feminine solidarity. The work takes its name from X’s farewell: “Take care of yourself.” The phrase, as multiple interpreters point out, implies a second clause: “Because I will no longer take care of you.” Calle’s experiment shows there’s another, sublime possibility for the aftermath: in your lowest and loneliest moments, others will understand for you, answer for you—take care of you.

—Elisa Gonzalez, author of two poems in issue no. 240 (Summer 2022)

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/woUtn4y

Comments

Post a Comment