Unless otherwise noted, all images are stills from Helen Cammock, I Will Keep My Soul, Siglio/Rivers/CAAM, 2023. Images courtesy of the artist and publishers. All rights reserved.

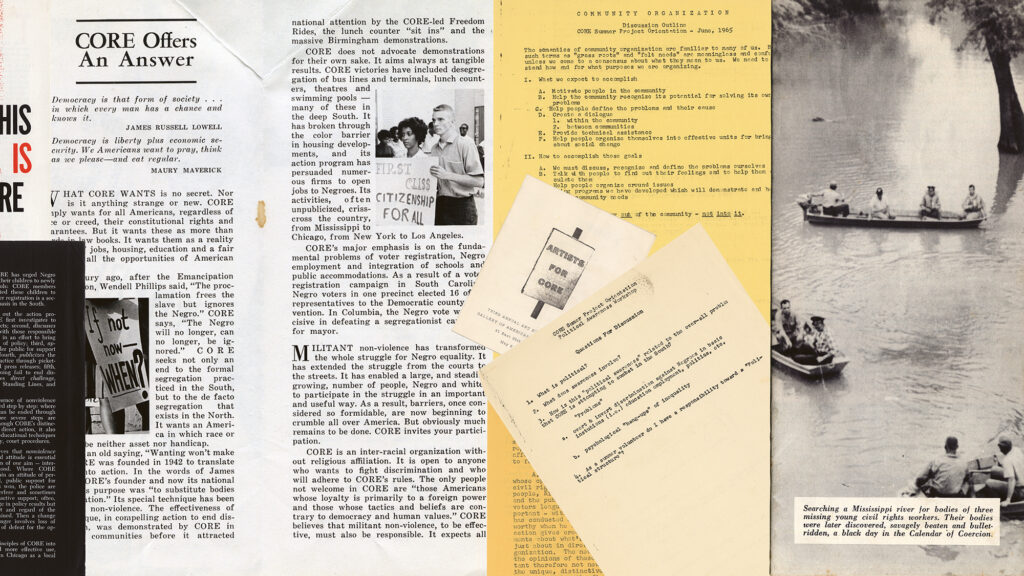

Collaged archival materials used in Helen Cammock’s I Will Keep My Soul, Siglio/Rivers/CAAM, 2023. Image courtesy of the artist, the publishers, and the Amistad Research Center.

I have seen the Mississippi. That is muddy water. I have seen the Saint Lawrence. That is crystal water. But the Thames is liquid history.

—John Burns, quoted in the Daily Mail, January 25, 1943

In the upper left quadrant of Minnesota, a small winding brook and its bubbling waters form the beginnings of a journey from north to south, catching streams and tributaries along its track through the heart of North America toward the Gulf of Mexico. The name given to this massive system made of more than 100,000 waterways is the Mississippi River, a riparian sweep with a drainage basin touching approximately 1.2 million square miles, or 40 percent of the continental United States. With sand and silt ever flowing toward the river’s mouth, a wild wetland of marshes, swamps, and bayous reigns, turning solid land into sponge in the vast network of alluvial floodplains known as the Mississippi Delta. Just under one hundred miles from the Mississippi’s mouth, the river takes a sudden turn southward, snaking east and then north in a final return to its southeasterly course. In this crescent-shaped curvature between river, lake, and gulf lies New Orleans, named after Philippe I, duc d’Orléans by the French Canadian naval officer and colonial administrator Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. In his correspondence with Philippe, Bienville described this magnificent system of watercourses as “filled with a mud as deep as its oceanbed” yet “unmistakably Divine” for its navigational and commercial potential. Through royal decree, Bienville was granted two parcels of land for the establishment of a “new France in this riverside”—land financed by France’s first colonial trading corporation, the Mississippi Company, and cleared and worked by the first enslaved Africans in Louisiana.

Colonization and enslavement have marked the course of the Mississippi’s historical fate, forming an entanglement between the natural conditions of the landscape and the voracious efforts to order the land and extract from it at any cost. The establishment of Black subjugation and enslavement as the guiding principles of the Mississippi Delta’s development commenced with the first-generation European settlers, who constructed no end of plantations along River Road, or the “German Coast,” in the early eighteenth century, as part of a systemic effort to harness the Mississippi’s unique qualities and resources for white landowning rights and profits. This project required decades of collaboration at the micro and macro levels, with parish administrators and Washington pundits, militias of engineers and surveyors, industrial titans, landowners, lawyers, and corporations united in the deregulation, mapping, draining, and domestication of the Mississippi Valley. The abstraction of the landscape into parcels of extractive capital instantiated slave-trading and slaveholding as the political, economic, cultural, and moral “mud and mortar” of the American project in the lower Delta.

These histories and environmental legacies remain visible all over the landscape of New Orleans. They are seen and felt in the imposing framework of the ancien régime grid, which since the city’s founding has divided and segregated rich and poor, free from unfree, white and Black, collaborating with the networks of reservoirs, levees, pumping systems, and public riverfronts constructed along the edge of the Mississippi to keep the edges of it in line. Some plantation complexes where sugarcane was once harvested and processed still stand along the riverbanks of River Road (with a few transformed into sites of public education). In the space between them, petrochemical refineries financed by Formosa, Shell, and ExxonMobil light the skies with carcinogens and toxic smoke above and fluorescent sludge below, their plants constructed on former plantation sites, ancestral burial grounds of Indigenous tribes, and cemeteries of the enslaved. The will to squeeze and strangle the land, the river, and the Black and brown peoples who live and work there goes on, improvising anew across time and space.

And yet, around this moon-formed meeting of water and land, a landscape has come into being through a constellation of resistances to these strategies of control and occupation. Movements and struggles against the tides of commodification persist in the natural and human worlds, both refusing to abide, seeping into the systems created to quell them. This is affirmed each time the Mississippi River spills over its banks. As Toni Morrison rightly reminds us, “they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places … it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” It is also instantiated in each recorded account of marronage, a permanent and common modality of resistance in the Delta wetlands, which turned the swamps into radical sites of commerce and kinship that sustained Black life and education, kept families together, and granted space for escape from enslavement. Revolts gathered up smaller reverberations of rebellion into visible and communal resistance, as on the night of January 8, 1811, when a group of more than five hundred Black people marched from LaPlace in St. John the Baptist Parish toward New Orleans along River Road. Armed with shovels and axes—the tools of their labor—they formed a thick cloud of protection behind their leader Charles Deslondes, an enslaved Creole of color. The historian Walter Johnson’s account of the 1811 revolt lends names and lands to those who participated: among their group were men named Cupidon, Al-Hassan, Janvier, and Diaca; some were American-born, African, or Creole; some hailed from Congo or the Akan; some were Christian, others Muslim. Each were organized into companies that reflected their origins, which together, representing the global stretch of cultures and communities violently destroyed by the transatlantic slave trade, were “dedicated to the single purpose of its overthrow.” Across their journey, they hid in the deep recesses of swamp and river, harnessing their labyrinthine waterways—places they knew and understood better than did their enemies—for protection. The muddy waters of the Mississippi hold these diasporic histories still; like all rivers, their edges are never still.

Far across the Atlantic Ocean lies the 205-mile length of the River Thames, which rises and flows west from Thames Head in Gloucestershire toward Tilbury in Essex and Gravesend in Kent, eventually spilling into the North Sea. Passing Oxford, Reading, and Slough, it cuts thick through the heart of London, offering drainage for England’s lowlands across the way. Shorter, shallower and gentler than the mighty Mississippi, the Thames’s history runs long—it was a catalyst for the organization and development of Europe. With the Roman founding of Londinium in A.D. 47 at a key crossing point over the Thames, the city on the river established itself as a major port and route for domestic trade and exchange, with barges traversing across a system of locks carrying timber, livestock, wool, and food from the fifteenth century forward. By the early stages of empire, the establishment of goods exchanges along the riverbank made the Thames a significant player in the organization of global capitalism and the transatlantic slave trade, beginning with the founding and charter of the Royal African Company in 1672 by King Charles II, which shaped a star-shaped network of transport between the west coast of Africa, Europe, the Caribbean, and the Americas. A lust for gold quickly shape-shifted to a lust for the land, waterways, and people inhabiting these sources, and inevitable competition and extractive greed would follow as England worked to build an industrial monopoly over the world. Banks on the Thames lent credit that financed the selling and commodification of human beings in colonial empires across the world, before and after 1808. Raw cotton and sugarcane, picked and processed by slaves in New Orleans, found their way to the exchanges in Liverpool, Bristol, and London via naval technologies and water routes invented by British civil servants. The Thames and its connective network of waterways was ever moving, pushing, and circulating goods and human beings by force and by choice into, across, and beyond Great Britain.

Around the curving bends of the River Thames and its tributaries, explosions of resistance have followed and formed, too—shifting, seizing, and interrupting the landscape and its story, the purpose and history of a place. More recently, on June 6, 2020, just twelve days following the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, Londoners took to the streets in the middle of a pandemic under the banner of Black Lives Matter. Standing shoulder to shoulder, the protesters edged their way along the Thames from Parliament Square toward Saint James Park and eventually to the U.S. Embassy in Vauxhall, in protest of incarceration and killing of Black people by the police; they paraded in front of the major seats of government and the institutions that have historically profited from slavery and its accompanying industries. In Bristol a day later, on June 7, 2020, an 1895 bronze statue of the British-born merchant and transatlantic slave trader Sir Edward Colson was toppled into the River Avon (a major tributary of the Thames) after decades of efforts, in recognition of Colson’s lucrative participation in the slave trade and the city’s subsequent whitewashing of his legacy as a philanthropist. Questions of accountability, transparency, and historical awakening remain the calling of all activists committed to liberation struggles.

One of the words that the artist Helen Cammock uses to describe her practice is seepage—a slow but steady escape or drainage of one thing into another, a cycle of movement backward and forward akin to the dances of a tide. Linking her process to the condition of water—as her work is forever expanding and leaking into and out of many material genres and modes—Cammock points to the animus at the heart of her project: movement, whether historical, political, geographical, or cultural. Finding and nurturing the sites of shift and movement—the places where they come into contact, pose gaps, interrupt, form connections, become liquid—remains Cammock’s most powerful methodological tool both inside the archives and in the materialization of her films and writing. Harnessing the power of water, the churn of history, and the spirit of memory that haunts them both, Cammock seeps and soaks into historical record, offering and opening space for the flow and traces of the past to link, return, and remember.

Helen Cammock is a British artist who uses film, photography, print, text, song, and performance to examine mainstream historical and contemporary narratives about Blackness, womanhood, oppression and resistance, wealth and power, and poverty and vulnerability. She was a joint recipient of the 2019 Turner Prize and has exhibited and performed her work in galleries and museums across the world.

Jordan Amirkhani serves as the deputy director and curator of the Rivers Institute for Contemporary Art & Thought. Her recent curatorial projects include Troy Montes-Michie: Rock of Eye and the 2021 Atlanta Biennial at Atlanta Contemporary. Her writing and criticism have garnered her a 2017 Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation Short-Form Writing Grant and three nominations for the Rabkin Prize in arts journalism.

From I Will Keep My Soul by Helen Cammock, Siglio/Rivers/CAAM, 2023.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/m7eWGld

Comments

Post a Comment