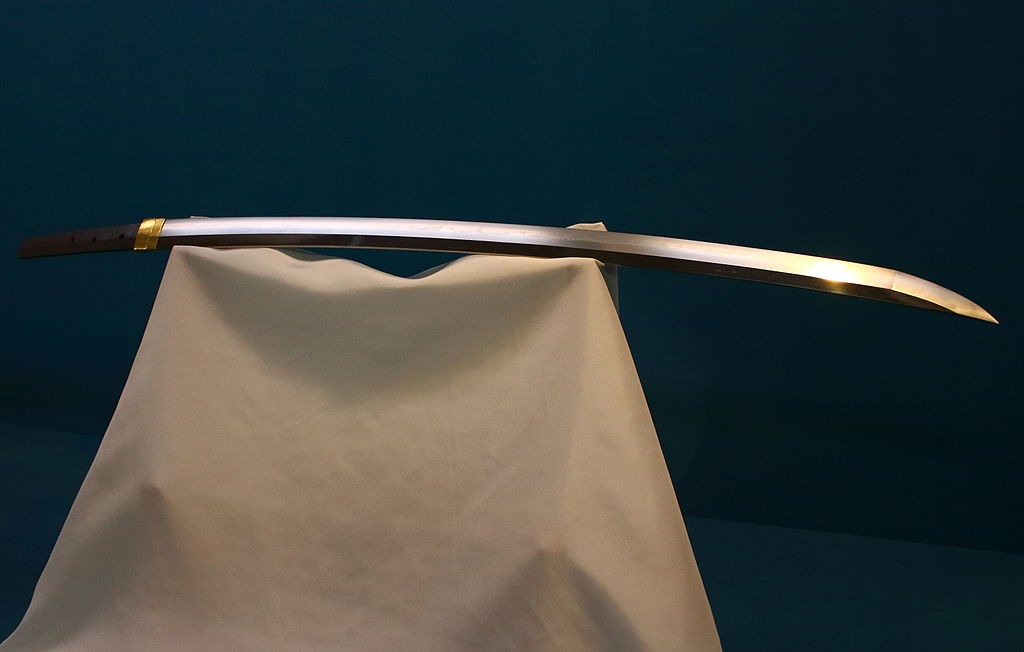

Katana. Photo by Kakidai, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Last week, I watched my first Kurosawa movie: Kagemusha, or Shadow Warrior. One of Kurosawa’s final productions, Kagemusha takes place in sixteenth-century Japan and tells the story of a thief who looks uncannily like Shingen, the leader of the Takeda clan, and who is employed to impersonate him in the event of his death to keep the clan together and protect it from its enemies. Shingen dies: enter the shadow warrior. This three-hour insight into feudal Japan, its structures of power, and the paradigm shift enacted by the introduction of guns onto the battlefield in the Sengoku period is mesmerizingly beautiful. Almost every shot could be a painting—cavalry battle scenes; the many councils of leaders draped with patterned kimonos; the delicate, expressive face of Tatsuya Nakadai, who plays both Shingen and his shadow. My favorite scene was the dream sequence: the kagemusha dreams of Shingen emerging dressed for battle, like an armored bird hatching from a shell, from the urn in which his corpse was deposited. The shadow flees, terrified, against a hallucinogenically colorful sky. The river water that splashes around his bare feet is dark like paint. I am ready to watch Seven Samurai.

—Isabella Hammad, author of “Gertrude”

I am in a book club that has only two rules. The first rule: any novel we read must have at least one murder. Nada, by the French writer Jean-Patrick Manchette, has, by my count, at least eight murders—and flashy ones at that. Originally published in 1973 and set in the hangover after the uprisings of 1968, the novel follows a group of leftist revolutionaries who kidnap the U.S. ambassador to France as a political statement. I’m not spoiling anything by saying that the revolutionaries and their scheme are doomed. The race to the bloody end fuses discussions on the legitimacy of using violence to further political aims with action scenes so gloriously paced that the book feels like a single exhale from start to finish. The characters include a jaded professional who hops from one leftist uprising to the next and a high school philosophy teacher who punches a colleague in the throat, shouting “fuck your face!” There’s also a mostly silent man who “wanted to shoot himself or just go to work—it was hard to say which,” and a rich girl who supplies the country house where the group stashes the ambassador. Her self-description is iconic: “My cool and chic exterior hides the wild flames of a burning hatred for a techno-bureaucratic capitalism whose cunt looks like a funeral urn and whose mug looks like a prick.”

It’s rare that a crime novel takes as an epigraph a quote from Hegel (“The heart that beats for the welfare of mankind passes therefore into the rage of frantic self-conceit …”), but Manchette is hardly an ordinary writer. His terse, propulsive sentences recall, a little, John le Carré, if le Carré had a passion for philosophy and a loathing of capitalism. Lucy Sante’s insightful introduction to Donald Nicholson-Smith’s translation points out Nada’s “theoretical shortcomings,” which Manchette himself acknowledged: the book fails to connect the Nada group with larger social movements and to depict the state interference, COINTELPRO-style, that would almost certainly occur. The likely Manchette mouthpiece backs out of the kidnapping because “terrorism is only justified when revolutionaries have no other means of expressing themselves and when the masses support them.” Still, when an ex-comrade condemns him “to eat shit and say thank you and cast blank ballots” for the rest of his life, it’s hard to disagree that something’s lacking in his pacific leftism, too. If Nada proves anything, it’s that “political” novels can be as unsettled as the politics we live with.

The second rule of my “Murder & Mayhem” book club: any book we read must have a movie adaptation. The 1974 adaptation of Nada, directed by Claude Chabrol, stars the Italian actor Fabio Testi, who is so handsome I googled him immediately, as you do with a fresh crush. The internet revealed that the man embodying the sexy terrorist was, later in his actual life, a conservative politician. The mismatch of image and reality, the disappointment of lust, the failure of people to live up to what we imagine of them, the ludicrous fantasies we construct for ourselves—all could be taken from Manchette.

—Elisa Gonzalez

As a poet, I spend most of my time experimenting with varying degrees of emphasis on conscious and unconscious ways of choosing language in order to find out what the results will be. The delight in this for me is getting to uncover whether a certain admixture of what is intended and what is received (dreamed, overheard, intuited) will bring about poems that affirm what I know or feel, reveal something unexpected, or something in between. I feel a kind of comfort and bewilderment as, with each poem, I’m reminded anew that, regardless of whatever knobs I think I’m turning or trying not to turn, writing allows the inexplicable, the wonderful, and the beyond me to occur. I am drawn to artists with similar interests, especially musicians. Two recent recordings, Mat Ball’s 2022 album Amplified Guitar and a new track from Kali Malone, “Does Spring Hide Its Joy v2.3” (one of nine versions of a composition that makes up her eponymously titled new album), are musical layerings of intentional, experimental, and spontaneous sound. A first layer of experience is created by playing specific notes; a second, by playing the same note at varying lengths, or by performing the same piece in different contexts over time. The interplay of these elements invites the listener to appreciate the variety of meanings or values that can be produced by this repetition. Both Mat Ball and Kali Malone also engage with an additional layer, something not entirely in their control: they allow their compositions to interact with amplifier feedback or acoustics, resulting in strange and gorgeous sounds. I’ve been listening and relistening to these pieces lately because they permit me to live in what I love about making poems: an embodied sense of agency and limitation, of logic and illogic, of variousness, and the opportunity to witness the collision of what I think I know with the unknowable nature of making.

—Peter Mishler, author of “My Blockchain”

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/EkNQrmY

Comments

Post a Comment