Years ago, while on assignment, I interviewed a man who spent what felt like hours showing me pictures of the various couches he was thinking of purchasing for his new home. The couches were ridiculous and abstract, as if the practical thing had been replaced with the idea of itself. They were long and narrow and metallic, or otherwise bulbous and overstuffed, like flesh permanently impressed by the tight grip of a corset. I thought he was deploying the couches as a kind of symbolic shorthand–to indicate to me his wealth and his taste, which obviously exceeded my own.

Now, years later, as I find myself in the midst of furnishing my own new home, I recognize in our exchange the telltale signs of a psychology that has been corrupted by the existential problem of populating an empty space. Obsession, fixation, compulsive confession: these weren’t the symptoms of a big ego–they were the symptoms of an ego that was being dissolved by interior design.

In November, on my first night in a new apartment, I became convinced that I needed a white couch, and that everyone in my life who had ever tried to dissuade me from buying one was simply hindered by their own neurotic insecurity. The only people who worry about stains, I told myself, are the people who lack the self-control not to make them. My former roommate, very politely, encouraged me to look at my white clothing as an indicator of the fate of my would-be white couch: all of it was spotted with brown or yellow or red or green, a personal ledger of every meal I had ever eaten. I told myself that a shirt had no relation to a sofa, and that the way I acted in one relationship with an inanimate object (neglectful, lazy) had nothing to do with the way I would act in my relationship with another (attentive, caring, precise).

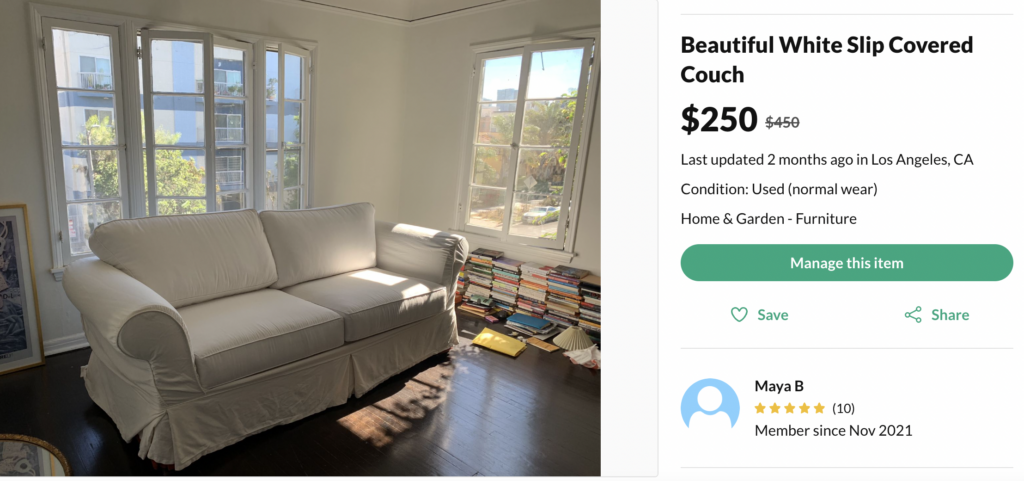

The next day, I drove to Beverly Hills and bought an immaculate slipcovered couch from a woman from the internet named Lina, who described, in careful detail, the couch’s requisite grooming routine. She seemed to feel that the couch’s covers had grown used to their pampering–monthly laundering, bleaching, steaming–and in fact depended upon it to maintain their identity. Somehow, she made it all sound so easy, the way a dentist can make even a herculean feat like flossing seem fundamental to the longevity of humankind. I didn’t know how to use bleach, and I didn’t own a steamer, but I was confident I would find the means to provide the couch with the conditions it needed to flourish. On Lina, I used the language I had been instructed, years before, to use on the volunteers who head dog adoption agencies: I wouldn’t change the couch to fit into my life; I would change my life to make room for the couch.

I paid two guys to carry it up three flights of stairs and into my living room, where I hoped we would live happily ever after. But in the context of all my other stuff––the books, letters, plants, and out-of-use chargers that I had collected over the course of many years–the couch looked offensive, idiotic, devoid of culture. (Even now, as I try to remember its color, all I can think is: blank.) When the room was empty, it had been full of potential. Now that it housed the couch, its fate seemed rigid and determined, but simultaneously vacuous, like the unending journey of a plastic nub floating in the wide-open sea.

The couch had nothing to do with me, and so I tried desperately to force it onto someone else. I divided everyone I encountered into two camps: people I respected, and people whose taste I judged to be compromised enough that they could be convinced that the couch was precious and necessary––that they wanted, and in fact needed, to take it out of my life and into their own. At parties, on the phone, and over text, I started speaking in the equivocating language of Craigslist ads, which quickly morphed into the lobotomized language of bad breakups: The couch was beautiful, but it didn’t work in my space; I loved it, but was no longer in love with it; it wasn’t it, it was me.

The couch was me, which was part of the problem: it reflected back to me how little I knew about my own desires, and then shamed me for allowing a mass-produced object to become a vessel for my sense of self. I feared I was losing my originality, that I was simply a replica, born to repeat my parents’ worst mistakes (they had raised me with some of the ugliest couches in the world). It didn’t help that my father, when I had asked him for his opinion on the couch before buying it, told me that it reminded him of the one he had just bought himself: “kind of uncomfortable. wouldn’t recommend it for you.”

For the next month, I posted ads on Craigslist, OfferUp, and Facebook Marketplace, but whenever it got to the point that someone agreed to come pick it up, I became convinced that they were interested in the couch only insofar as it provided them a practical means of entering my life for the express purpose of ending it. So, I would stop responding, and then begin telling myself that my life was more important to me than my dislike of the couch––that I could grow to love it, and even persuade it to change. Sawing off the legs, dyeing the slipcover: both seemed like potentially groundbreaking alterations. But I never altered anything, and so the couch remained pristine, tidy, and white: an emblem of all of the bad decisions I had made in the past, was making in the present, and would continue to make long into my meaningless future.

Eventually, just after Thanksgiving, a young woman messaged me, telling me that she hoped to buy the couch for her mother, that it was––in fact––just the thing her mother had been looking for. Her story, like the rest, seemed completely implausible to me. But I gave her my address anyway. She would come to my apartment on Tuesday, and I would either survive the interaction or I wouldn’t, but in both scenarios something, mercifully, would cease to exist: myself, the couch, or my infatuation with it.

Maya Binyam is a contributing editor at The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/R0UTpzS

Comments

Post a Comment