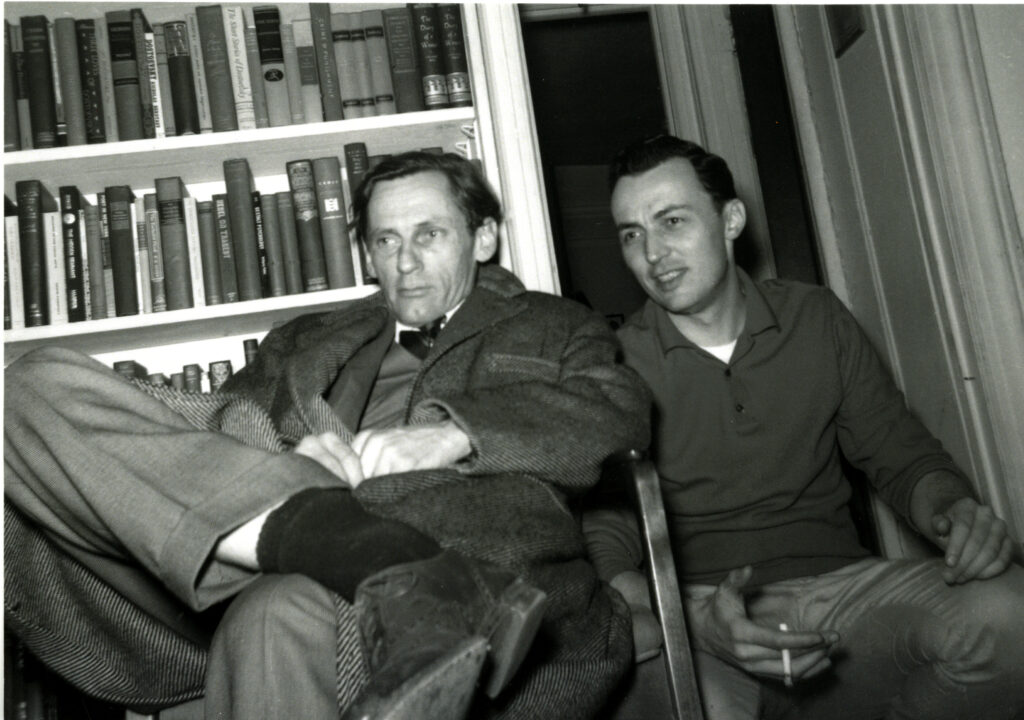

William Gaddis and David Markson. Courtesy of the estate of William Gaddis.

Although William Gaddis’s first novel, The Recognitions, is now regarded as one of the great American novels of the second half of the twentieth century, it was panned upon its publication in March 1955. Among the early few who recognized its greatness was the future novelist David Markson, who read it shortly after it came out, was so impressed that he reread it a month or two later, and then decided to write Gaddis a fan letter. Too depressed by the book’s reviews, Gaddis filed away the letter unanswered. Markson proselytized vigorously on the novel’s behalf over the next six years: he talked the publisher Aaron Asher into reissuing the remaindered novel in paperback, and in his own first novel, Epitaph for a Tramp, Markson included a scene in which the detective protagonist is poking around a literature student’s apartment and finds in the typewriter the conclusion to an essay: “And thus it is my conclusion that The Recognitions by William Gaddis is not merely the best American first novel of our time, but perhaps the most significant single volume in all American fiction since Moby Dick, a book so broad in scope, so rich in comedy and so profound in symbolic inference that—” Learning of Markson’s efforts from another fan named Tom Jenkins, Gaddis finally answered Markson’s 1955 letter: “After lo these many (six) years.” They would continue to correspond and saw each other occasionally until Gaddis’s death in 1998.

Markson opens the exchange with a canceled salutation to a minor character in The Recognitions who receives a long, rambling letter, and he continues with allusions to other characters, books, and topics in the novel, rendered in Gaddis’s style.

—Steven Moore

717 Greenwich Street

New York City

11 June 55

Dear Dr. Weisgall William Gaddis:

Christ. Christ, Christ, Christ, Christ, Christ. What I want to know is, outside of perhaps The Destruction of the Destruction of the Destruction, what the hell is left to write? Or read, I mean Chrahst! This drunk staggers up to a sandwich man in Times Square, seeing: Filth in our food, spit in Pepsi Cola, free circular … and lurches off screaming: “Jesus, now there’s nothin left to eat even!” Which is how you make me feel. Of course there’s always the chance of Otto’s Return (to Sorrento?) or, say, They Survived: The Saga of Mr. Inononu and Mr. Schmuck, or even Daddy Was a Monk, by the Bildow baby’s baby (as told to of course Max), but why bother? I mean, Chrahst!

But thanks anyhow.

I get it: the method and the matter, although sometimes less of the matter than I might, lacking certain knowledges; but when where the matter is, as it were, foreign, the patterns are there, and more’s the pity if all the expansion can’t be followed. But then hell, you do explain everything, one time or another, in literal terms: I mean Valentine does actually tell him [Wyatt] he’ll eat his father, and his father does actually tell him that when a king is eaten there’s sacrament, and he does actually say his father was a king; or if you miss the poodle running in circles, can you also miss the uneven teeth and the shape of the ears, or lavender used as a “medium”? (Forgive this: I’m merely trying to indicate awareness of more than the literal.) It’s a remarkably great book, and if there have been two (which I know of) which came before it, the step you’ve taken beyond them is this: that you not only relate present to past (act to myth, I mean Chrahst) but also present to present, reducing things so delightfully to absurdities, yet destroying them not. (I might say “a little always sticks,” or would that be pressing it?) And what in hell am I doing telling you what you’ve done, when all I want to say is … (My, your friend is writing for a rather small audience, isn’t he?) … all I want to say is that if I didn’t write the book myself in another life then you wrote it for … (O Doctor, how the meek presume) … for me. And so thanks.

Listen: what I mean is, there are “moments of exaltation” in discovery, also. And obviously I don’t merely mean that I “get it.” There are things like, say, Anselm, after raving, suddenly: “A duet … sung by women, women’s voices,” or … say, Esme, alone … or for Christ sake even poor old Mr. Feddle and that faked dust jacket. And God God the laughter, and where were you when the … Oh the hell, I just thought you would be pleased to know that someone knows what Gaddis hath wrought.

Thanks.

Does this make any sense? I don’t write to “authors” (although I must admit I’ve been known to scribble authors’ inscriptions in friends’ books—bibles only—and damn it no matter how far beyond it all a guy thinks he is, you do manage to have him squirming at times). Anyhow, nothing is intended here. Probably there is a customary way: Dear Mr. Gaddis, I just loved your gorgeous book and I think Mithra is so charming and … I ask you, if Rose was mad, is rose madder?

Do you know Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano? It is the only other thing I know outside of Joyce with so much “amplifying experience” tied together so well. (The terms are difficult to avoid; I mean much more than that.) Anyhow I don’t know many better compliments than the comparison. Or do I sound like the reviews: this book must be compared to Ulysses BUT. God, how they are unaware of the self-devastation of their own ironies, or for that matter of their ironies themselves. Must be compared but: and oh, the militant stupidity of that piece by Granville Hicks [in the New York Times Book Review]. What a charming bloody situation it is when you have to accustom yourself to the profound subtleties of their unawareness in order to know which books are probably worth reading. But what the hell, a work of art is more than a think of “perfect necessity”; it is also an undeniable fact. It exists. Est ergo est. And damned few other brands can make that statement.

In the Viareggio [a bar in the novel]:

—Willie Gaddis? Who doesn’t know him?

—If you can call my mother Jocasta, and me narcissistic …

—That book. He used to run into Harcourt Brace twice a week screaming about this great conversation he heard last night, he had to get it in.

—Listen, your mother still slips a toothbrush into her purse before she goes out to the bar.

—Well, a couple hundred pages, but I mean Chrahst, so the guy’s read everything, I mean why bother …

—My mother …

—I know this guy, says it’s the best book in years. Symbolic for Christ sake. I mean anything that’s a little obscure …

Listen, listen, listen: this could go on forever. You done good, which is all there is to say. If you are ever around I would very much like to catch you for a drink or two (above Fourteenth Street) but that is neither here nor there. But you’ve heard the bells, ringing you on, and what else matters?

With much admiration,

David Markson

New York City 3, New York

28 February 1961

Dear David Markson.

After lo these many (six) years—or these many low (sick) years—if I can presume to answer yours dated 11 June ’55: I could evade embarrassment by saying that it had indeed been misdirected to Dr. Weisgall and reached me only now, but I’m afraid you know us both too well. In fact I was in low enough state for a good while after the book came out that I could not find it in me to answer letters that said anything, only those (to quote yours again) that offered “I just loved your gorgeous book and I think Mithra is so charming …” Partly appalled at what I counted then the book’s apparent failure, partly wearied at the prospect of contention, advice and criticism, and partly just drained of any more supporting arguments, as honestly embarrassed at high praise as resentful of patronizing censure. And I must say, things (people) don’t change, just get more so; and I think there is still the mixture, waiting to greet such continuing interest as yours, of vain gratification and fear of being found out, still ridden with the notion of the people as a fatuous jury (counting reviewers as people), publishers the police station house (where if as I trust you must have some experience of being brought in, you know what I mean by their dulled but flattering indifference to your precious crime: they see them every day), and finally the perfect book as, inevitably, the perfect crime (the point of this last phrase being, for some reason which insists further development of this rambling metaphor, that the criminal is never caught). So, as you may see by the letterhead on the backside here, I am hung up with an operation of international piracy that deals in drugs, writing speeches on the balance of payments deficit but mostly staring out the window, serving the goal that Basil Valentine damned in “the people, whose idea of necessity is paying the gas bill” … (a little frightening how easily it all comes back). But sustained by the secret awareness that the secret police, Jack Green and yourself and some others, may expose it all yet.

This intervention by Tom Jenkins was indeed a happy accident (though, to exhaust the above, there are no accidents in Interpol), and I was highly entertained by the page-in-the-typewriter in your Epitaph for a Tramp. I of course had to go back and find the context (properly left-handed), then back to the beginning to find the context of the context, and finally through to the end and your fine cool dialogue (monologue) which I envied and realized how far all that had come since ’51 and 2, how refined from such crudities as “Daddy-o, up in thy way-out pad …” And it being the only “cop story” (phrase via Tom Jenkins) or maybe second or third that I’ve read, had a fine time with it. (And not that you’d entered it as a Great Book; but great God! have you seen the writing in such things as Exodus and Anatomy of a Murder? Can one ever cease to be appalled at how little is asked?)

I should add I am somewhat stirred at the moment regarding the possibility of being exhumed in paperback, one of the “better” houses (Meridian) has apparently made an offer to Harcourt Brace, who since they brought it out surreptitiously in ’55 have seemed quite content to leave it lay where Jesus flung it, but now I gather begin to suspect that they have something of value and are going to be quite as brave as the dog in the manger about protecting it. Though they may surprise me by doing the decent and I should not anticipate their depravity so high-handedly I suppose. Very little money involved but publication (in the real sense of the word) which might be welcome novelty.

And to really wring the throat of absurdity—having found publishers a razor’s edge tribe between phoniness and dishonesty—I have been working on a play, a presently overlong and overcomplicated and really quite straight figment of the Civil War: publishers almost shine in comparison to the show-business staples, as “I never read anything over a hundred pages“ or, hefting the script, (without opening it), “Too long.” The consummate annoyance though being that gap between reading the press (publicity) interview-profile of a currently successful Broadway director whose lament over the difficulty of getting hold of “plays of ideas” simply rings in one’s head as one’s agent, having struggled through it, shakes his head in baleful awe and delivers the hopeless compliment, “… but it’s a play of ideas”—a real escape hatch for everybody in the “game” (a felicitous word) whose one idea coming and going is $. And I’m behaving as though all this is news to me.

Incidentally—or rather not incidentally at all, quite hungrily—Jenkins mentioned from a letter of yours a most provocative phrase from a comment by Malcolm Lowry on The Recognitions which whetted my paranoid appetite, I am most curious to know what he might have said about it (or rather what he did say about it, with any thorns left on). I cannot say I read his book which came out when I was in Mexico, 1947 as I remember, and I started it, found it coming both too close to home and too far from what I thought I was trying to do, and lost or had it lifted from me before I ever resolved things. (Yes, in my case one of the books that the book-club ads blackmail the vacuum with “Have you caught yourself saying Yes, I’ve been meaning to read it …” (they mean Exodus).) But I am picking up a copy for a new look. Good luck on your current obsession.

with best regards,

W. Gaddis

Gaddis’s letter to Markson will be published by New York Review Books in The Letters of William Gaddis in November 2023.

William Gaddis (1922–1998) was born in Manhattan and reared on Long Island. The Recognitions was published in 1955 to largely negative reviews, though it found an underground following. J R, his second novel, and A Frolic of His Own, his fourth novel, both won the National Book Award.

David Markson (1927–2010) was born in Albany and lived in New York City until his death. His novels include Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Reader’s Block, Springer’s Progress, and Vanishing Point.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/WUuZ96L

Comments

Post a Comment