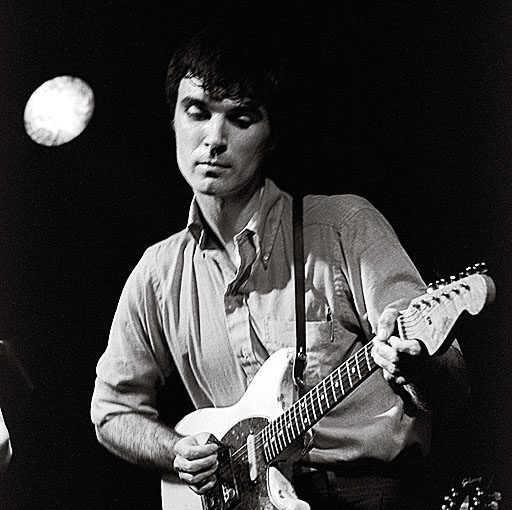

David Byrne, 1978. Photograph by Michael Markos. Wikimedia Commons, Licensed under CCO 2.0.

I think the best love songs are simple. They’re simple because love isn’t, simple because we need to dream a little. Complexity, ambiguity, doubt—they can have their place in novels or in the movies. A love song lets you live in the fantasy of the absolute; maybe that’s also why they last only a couple of minutes. And that’s why we carry them with us, play and replay them until they wear out like old clothes. They stand for too much.

I have many songs that mark the time of particular relationships, both their highs and the lows of their dissolution. I’ve played songs on repeat enough to drive people crazy, and I’ve locked myself in my room to listen to late-period Billie Holiday with the lights off. But I have only one renewable love song, which I’ve brought with me through all my relationships: the Talking Heads’ “This Must Be the Place (Naive Melody).” That’s probably because, although it pains me slightly to say this, it began for me as a family romance. When my parents were young and childless and living in Seattle, they saw a sign for the movie Stop Making Sense, Jonathan Demme’s Talking Heads concert film, at a theater near the Pike Place Market. I don’t think my parents were particularly interested in the hip music of the eighties—they just liked the name of the movie. They bought tickets on a whim and went inside.

So the cassette-tape soundtrack of Stop Making Sense was a sonic canvas of my childhood. But it wasn’t until I saw the movie for myself, in high school—watching it with a girl, making feeble couch-based sexual advances—that I was reawakened to the song. It’s unusual for the Heads, who are better known for blending angular, art-school/CBGB cool with African-polyrhythm borrowings. The song is very straightforward. Sentimental, even. But a great love song should be sentimental. Why wouldn’t you try to feel everything you possibly can? The groove begins straightaway—simple drums, the bounce of the bassline, some light synth stabs. A perfect little loop. After a couple of repeats, a bubbling riff kicks in, with a soft, pipelike quality to its pitch-shifting. It reminds me of a calliope, although I’ve never listened to one in real life—it’s children’s music from some other, unlived existence: “Love me till my heart stops / love me till I’m dead.”

That’s the naive part, and isn’t accessing innocence without curdling one of the most difficult things art can do? In the movie, David Byrne is the avatar of unrepressed feelings: gesticulating, shaking, yelping, and squawking. As he says in a promotional interview for the film, wearing his now-famous big gray suit, the body gets bigger so the head can get smaller. In the film’s performance of “Naive Melody,” he performs a pas de deux with a floor lamp, elegant and absurd and melancholy-ordinary. Still, despite the naïveté, there’s something sophisticated about the rest of the title, that “this” must (emphatically) be the place. Where is “this”? It’s anywhere we point to, anywhere we call home. We try it out and see if it works. There’s something beautiful and agonizing about recognizing love as a placeholder, a space we’re always trying to fill. Every day we have to conduct the experiment of calling that love our own. You could be anyone. You could be mine.

David Schurman Wallace is a writer living in New York City. He is an advisory editor at the Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/ZBJcmSF

Comments

Post a Comment