All images courtesy of Peter Mishler.

How did you come up with the title for this poem? Were there other titles you thought about?

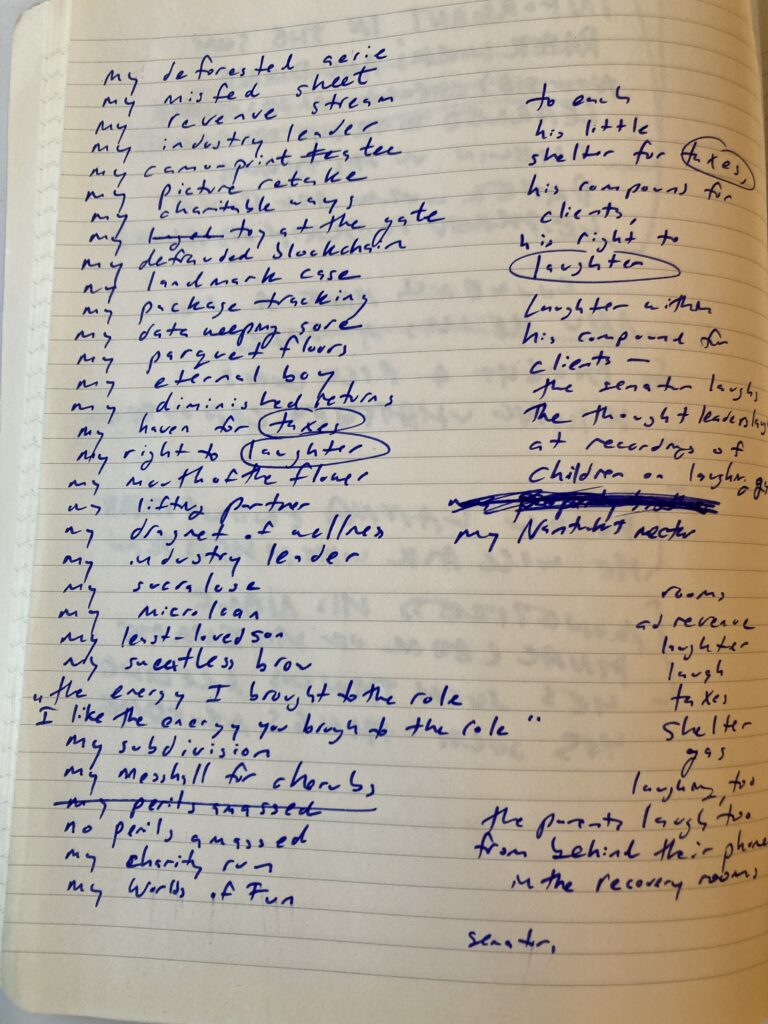

When “What even is a blockchain/an NFT?” was the subject of conversation everywhere you went, I got interested in the technology’s claim that it creates an “immutable record” of each transaction along the chain of a digital asset’s ownership. I wanted to write a series of personal statements that could not erase what preceded them. Then I noticed this idea was also connected to a certain type of statement—made by a certain type of man—that we’ve seen often, recently: a public apology by someone whose behavior grossly outweighs their supposed contrition. No matter how much they try to distance themselves from themselves, the mea culpa still contains something that can’t be undone: it’s an “immutable record” of all the actions that preceded their apologies, which sound far more like launching an asset than sincerity. So, I thought I would write in the voice of a corrupted consciousness that mirrors the workings of this new bro-corrupted mechanism of capitalism.

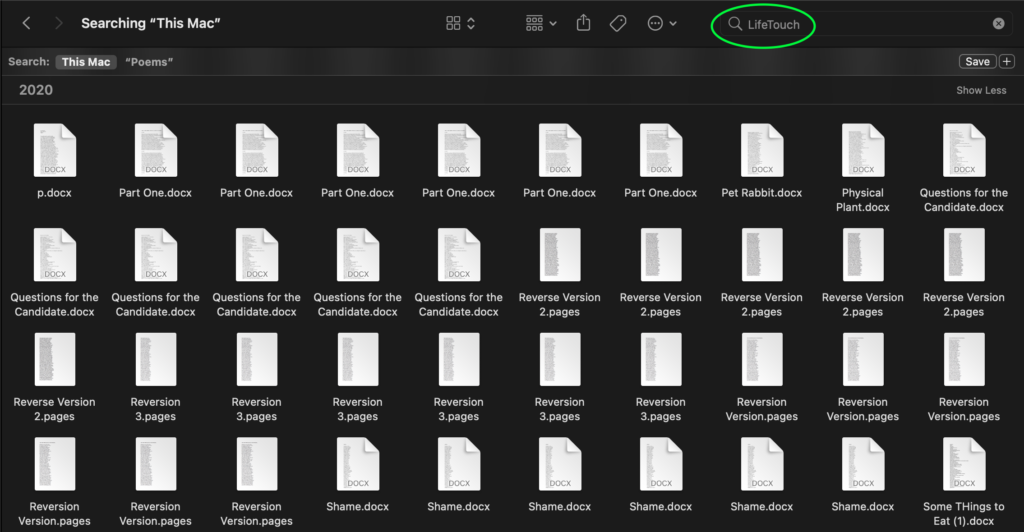

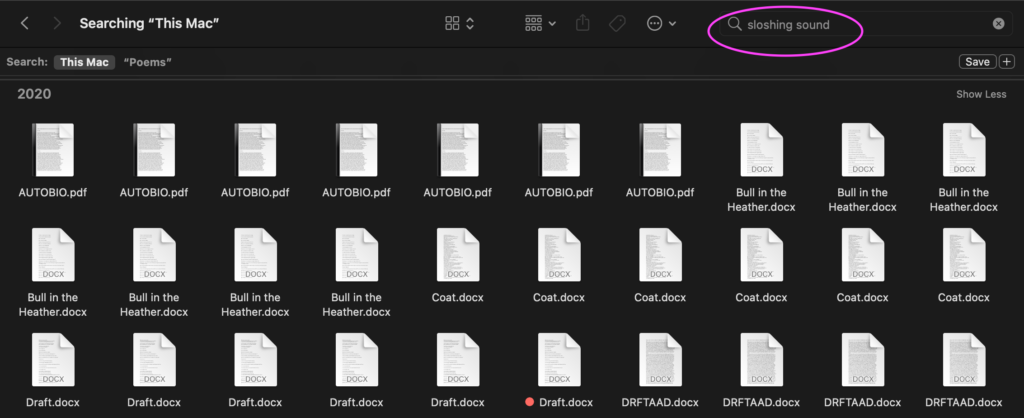

I often save my drafts under file names that function as little code words or reminders about a feeling I was having during that day’s writing. “My Blockchain,” though, remained the official title, even as I played with other ways of reminding myself what I was writing.

How did writing this poem start for you?

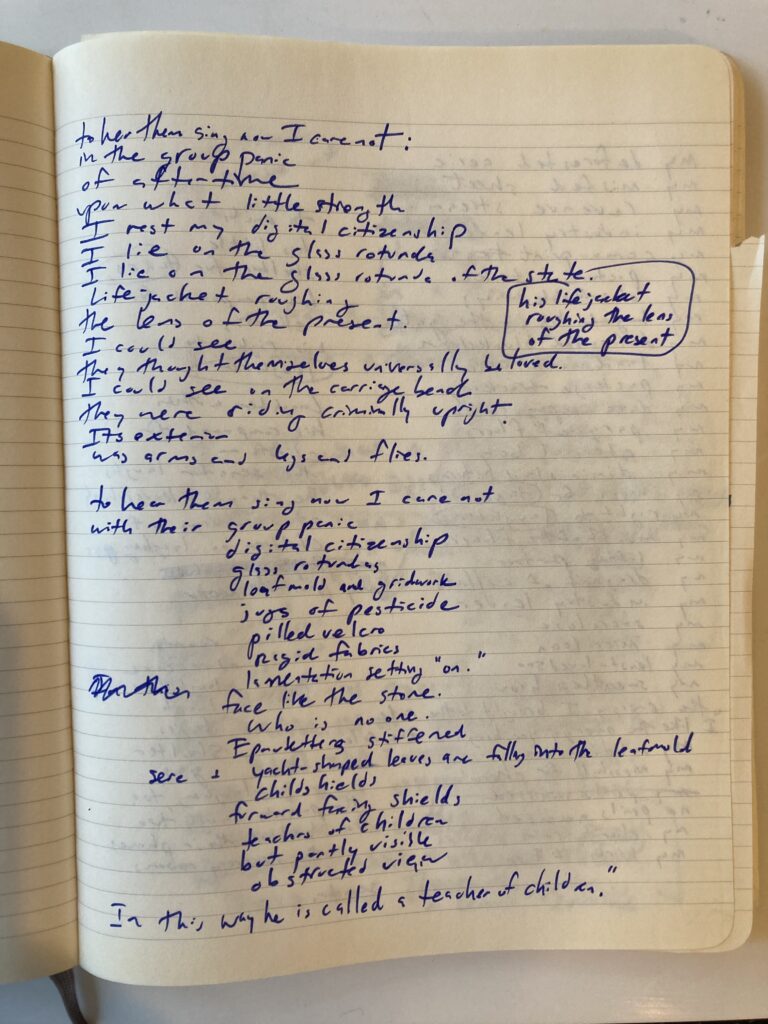

I knew I wanted to use what ultimately became the final line of the poem—“to hear men sing now I care not”—as an opening or closing. At some point I began to read the line as a turn in the poem. I knew my task would be like the task of a sonnet: to accomplish that turn. I worked on this on and off for a couple of years with various lines, images, and half rhymes coming in and out, though one idea remained consistent: I knew that the penultimate lines would need to complicate the final line’s potential to be read as pedantry. What better way to do that than to imagine it being voiced by a certain kind of man—the type who would sing about himself for seventeen lines and then, in a different register, swiftly renounce that singing on some moral high ground?

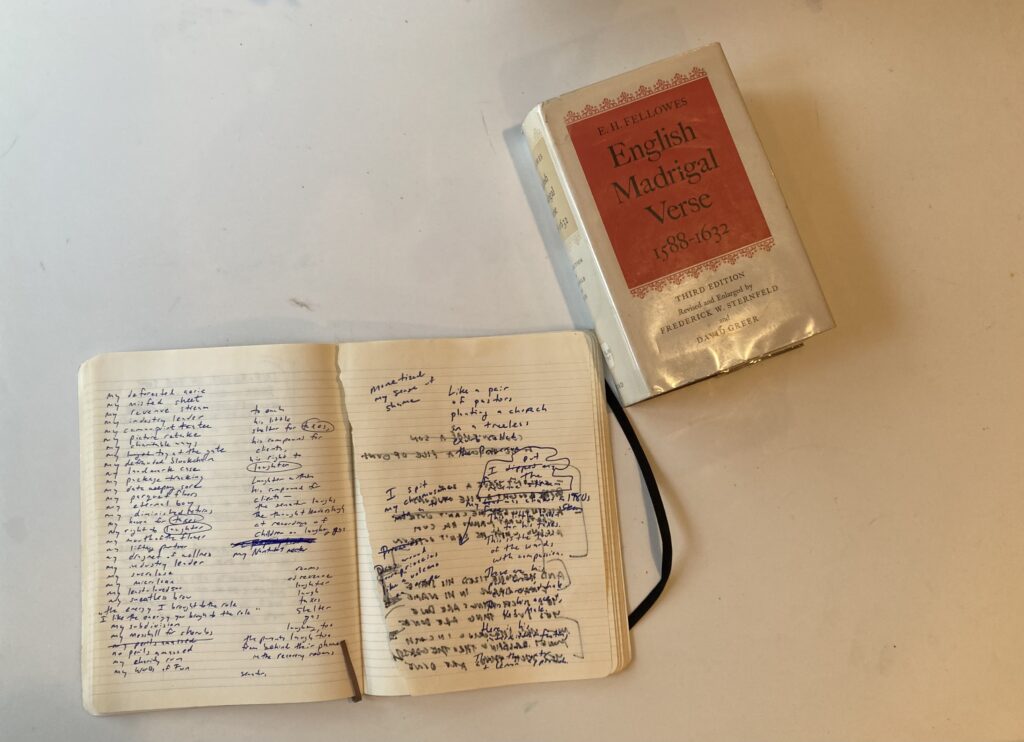

An early draft of “My Blockchain.”

What were you listening to/reading/watching while you were writing this?

Over the past couple of years, I’ve been playing music for a record I’m making that converses with a longer poetry manuscript, which includes this poem. I’ve also been writing more, rather than reading. This is very new for me, after many years of compulsive reading. But I’ve decided that at this point in my life I just want to make as much art as possible. So I read the Friday and Sunday paper, and then I get back to my own thing. That’s how I spend my time if I’m not at work or with my wife and children.

Some of the files for drafts of this poem took their name from the Sonic Youth song “Bull in the Heather.” Looking back at these drafts reminded me that I was listening to that song over and over again while writing what became “My Blockchain” because the cadence of that song felt like the right accompaniment for single-line stanzas.

Are there hard and easy poems to write?

The thing that can make writing hard for me is having an expectation that a poem should come together sooner rather than later. To prevent feeling this way, after I’ve published a poem, I compile all the drafts that led to it in a pdf, and on the final page I put the finished poem. These can be very long documents, spanning a number of years, and I look through them to remind myself how long it can take for something to happen. It’s important to remind myself that all writing—whether I perceive it to be productive or unproductive—is always headed in the direction of realizing a finished poem. My main responsibility is to trust that and show up for that, and give myself less room to worry about what poem is going to come, and when.

Playing with rhymes.

When did you know this poem was finished?

Having a poem appear in a magazine makes it a lot easier to stop working on it. I think that’s the moment I finally allow myself to leave it alone and move on to something else, because I know then that it’s communicating something to another person outside of what I’m hearing in it on my own. That doesn’t mean I won’t eventually return to it—but it’s more likely that I’ll return to what I think I might have missed out on in it by writing something new. I find it easier to revise a poem by writing a completely new one where I bring some of the challenges of the old one into play. That way I don’t overwork the old poem or get too far away from its energy, and I get to have that fresh-start feeling.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends?

My wife is a poet, but we spend as little time as possible talking about our work, and we don’t typically share it with each other. We talk a lot about art and music and movies and things, but not about our writing. It’s been really cool at readings when one of us has new work to share and the other gets to hear it as an audience member for the first time, or when one of us gets to read the other’s work first in a magazine. We do, of course, toast to each other’s publications and books, but keeping the act of writing quiet is preferable and even sustaining. It affirms the significance of our individuality and the private creative act. My wife read “My Blockchain” for the first time in the issue when it arrived in the mail, and she very knowingly said, “I see what you’re doing.” That was all I needed to hear. It was a big compliment.

Peter Mishler’s debut poetry collection is Fludde.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/WZ8yMnA

Comments

Post a Comment