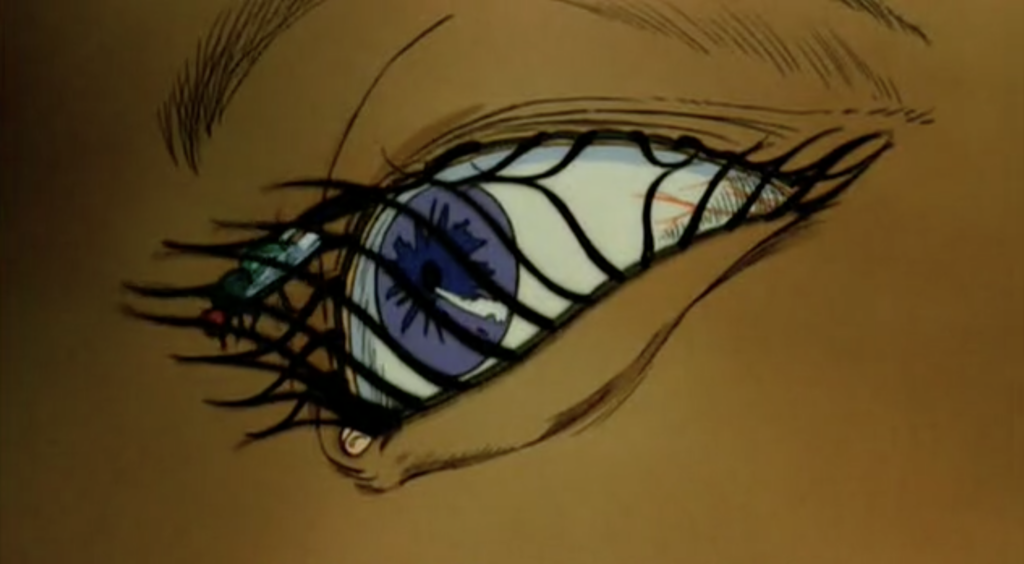

Detail from the title sequence of Peter Chung’s Æon Flux.

What is this video? A plot summary might run something like this: A low-quality cell phone records, in slow motion, a small suburban lake being stocked with fish. A long, transparent inflatable tube runs the fish from a truck across a lawn and into the lake. They get stuck; they struggle; they clog the tube; they swim, weakly, upstream; and eventually men in aprons (the fish stockers?) pick up the tube and force the last fish out. Neighbors (I presume) have gathered to watch the process—children are filming, a lone man reaches out piteously to stroke the clots of confused fish through the tube, and a goldendoodle’s fluffy head bobs in and out of the frame. The video, by the artist Barrett White, borrows its grand title—“Pessimism of the Intellect, Optimism of the Will”—from Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and letters, in which that phrase describes the coexistence of apparently contradictory orientations to the world. White sets the video’s banal footage to Arvo Pärt’s solemn “Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten,” complete with periodically tolling bell.

The video’s appeal is its constant oscillation between tragedy and, well, bathos. At first, the video seems like a funny TikTok—grand music, slo-mo, grainy vertical footage, silly suburban fish situation. Ha. But then it goes on for almost eight minutes? Just as Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” becomes a gorgeous and resigned dirge when slowed down (recommend), something about the dilation of time changes the tonality of White’s video. It creates space for an aesthetically sensible movement between the video’s contradictory tonal cues. This extension of time allows for multiple and layered juxtapositions of grand and banal. You can really feel this circulation when you’re watching it—feel the way your own feeling turns into its apparent opposite, and back.

I’ve returned to this video repeatedly since I first saw it last year. It has a total of 110 views as of February 1, at least ten of which are mine. Sometimes I notice the way the tumble of the fish’s bodies looks like a Renaissance etching of sinners tumbling into hell; sometimes I notice the bearded man’s camo pants; sometimes I notice the confused pathos of the man who leans out to touch the knot of disoriented trout—and I feel, like him, the terror of the fish, and sadness for them. Like the fish, I feel the force of the cues at play—for them, it’s water pushing one way; for me, it’s the music’s command to FEEL! PATHOS NOW!, which also has the ironic overlay of saying how silly it is, to feel that. But I resist: I don’t like being told what to feel, and if I do feel something like mourning, maybe I’m a fool. Maybe those feelings are out of scale, out of tune with the world as it actually is. Or maybe when I see this situation as ridiculous, and I’ve accepted a certain kind of banality, that’s when I’m out of tune with the world as it actually is. Maybe this tube leads to death. Or maybe it leads to another slightly larger holding tank that is just fine.

—Kirsten (Kai) Ihns, reader

Barn sour, an equestrian term, describes a domesticated horse who doesn’t want to leave its home. A barn sour horse will resist being taken from its stable, often violently. If they are forced out, they might bolt back home, throwing their rider off their back, sometimes trampling them. The term has been taken as the name for a mysterious sound-collage artist from Winnipeg, Canada. I came across Barn Sour’s tape horses fucked over the head with bricks in late 2019, on which sparse harmonies on a detuned piano are dubbed over recordings of manic laughter and guttural glossolalia. It is just under nine minutes long, incredibly disturbing, and absolutely mesmerizing. It was released under two pseudonyms, one of which is C. Lara, the name of a real racehorse. The other is James Druck, a long-dead fraudster implicated in a scheme to kill show horses in order to collect insurance money. (James Druck’s daughter, whose childhood horse was among the horses killed, is also the inspiration for a central character in Jay McInerney’s novel Story of My Life.)

I feel like I’m watching scenes from a horror movie on a deteriorating VHS tape in a large, cold, empty house: the gruesome images are hard to make out; I can’t tell if the fuzziness is making the experience more or less fascinating or nauseating. Most of Barn Sour’s releases have titles invoking an esoteric reference to equine terminology. Soap & Glue, their compendium album, released by Penultimate Press this year, takes its name from two products historically made from ground-up horse parts. It’s a suitable name for the album, which is full of reworkings and rebludgeonings of their previously released material—but also because it is billed as Barn Sour’s final release, their death, their body of work ground to a pulp. Join them for a final foal-y à deux before they trot back to their barn for good.

—Troy Schipdam, reader

While visiting my hometown this winter, mildly jet-lagged, I started waking up at 4 A.M. To kill time before the sun rose, I’d watch an animated sci-fi show from the early nineties. Æon Flux—which aired between 1991 and 1995 as a series of six experimental films on MTV’s late-night showcase for indie animators—is perfectly suited for the borderland between dreaming and consciousness. In the iconic title sequence, an insect lands on a woman’s cheek and crawls into her open, pupilless eye only to be captured in its lashes, as in a Venus flytrap, when the lids snap shut. The eye reopens and the pupil swivels into place, bringing its prey into focus. Many of the elements that earned the show its cult following are there in the intro: hallucinatory images, biopunk body augmentation, a bit of eroticized violence. Set in an ultramodern dystopia, Æon Flux follows the titular character, a femme fatale–type (slicked-down black hair, violet irises, bondage gear) who works as an assassin for the resistance. We quickly learn that Æon is a morally ambiguous antiheroine traveling between two competing societies: the anarchic Monica and the technocratic police state Bregna, ruled by an Aryan-blond despot (and Æon’s nemesis-lover) called Trevor Goodchild. Æon is frequently killed and reincarnated before the credits roll.

Æon Flux is a masterpiece of visual storytelling. Its early episodes are free of dialogue and instead rely heavily on clusters of impressions and shifts in perspective. Influenced by Egon Schiele, the French cartoonist Moebius, and manga artists like Kazuo Umezu and Osamu Tezuka, the creator and director Peter Chung’s style is defined by expressive lines. He prioritizes evocative character design—elongated, sinewy figures, angular architecture—over surface detail. The series is a combination of fetish content, classic sci-fi, and, according to some fan theories, Gnostic symbolism. In one episode, the body of a soldier is reanimated so his belly can be used to gestate a godlike being with an iridescent halo. In another, a woman’s shattered vertebra is surgically removed, allowing her to rotate her body a full 360 degrees, and replaced with a device that reseals her spinal column with the push of a button. Late in the series, Æon clones her own body in a biotech laboratory, and, in a campy allusion to Narcissus and his reflection, she kisses her surrogate self as she emerges from a pool of water.

Consuming a nonstop stream of images like this for a few hours each morning, under my parents’ roof once more, left me feeling delirious and impossibly old. But Chung’s characters, with their contortionist acrobatics and cyberpunk experiments, also plucked the string inside me that tethers me to my kid self, the one who read books about dystopian futures, kissed girls in their bedroom once their parents had gone to sleep, and tried to decide what they wanted to do with their body.

—Jay Graham, reader

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/KbdRHEr

Comments

Post a Comment