A few days before the Review’s new Spring issue went to print, the poet Rita Dove called me from her Charlottesville home to set a few facts straight. She and her husband, the German novelist Fred Viebahn, are night owls—emails from Dove often land around 9 A.M., just before bedtime—and they had just spent several long nights poring over her interview, which was conducted by Kevin Young and which spans Dove’s childhood in Akron, Ohio, where her father was the first Black chemist at the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company; her adventures with the German language; her experience as poet laureate of the United States, between 1993 and 1995; and her love of ballroom dancing and of sewing, during which she might “find the solution for an enjambment” halfway through stitching a seam. Working their way through the conversation, she and Viebahn had confirmed or emended the kinds of small but crucial details that are also the material of Dove’s poems: the number of siblings in her father’s family, the color of the book that inspired the poem “Parsley,” the name of the German lettering in which her childhood copy of Friedrich Schiller’s Das Lied von der Glocke was printed (not Sütterlin, it transpired, but Fraktur). We talked through her corrections, and then Dove produced a final fact that caught me by surprise. Two decades ago, she said, she had been preparing to be interviewed for The Paris Review by George Plimpton. He’d called to set a date for their first conversation, and the next day, she said, came the shocking news that he had died.

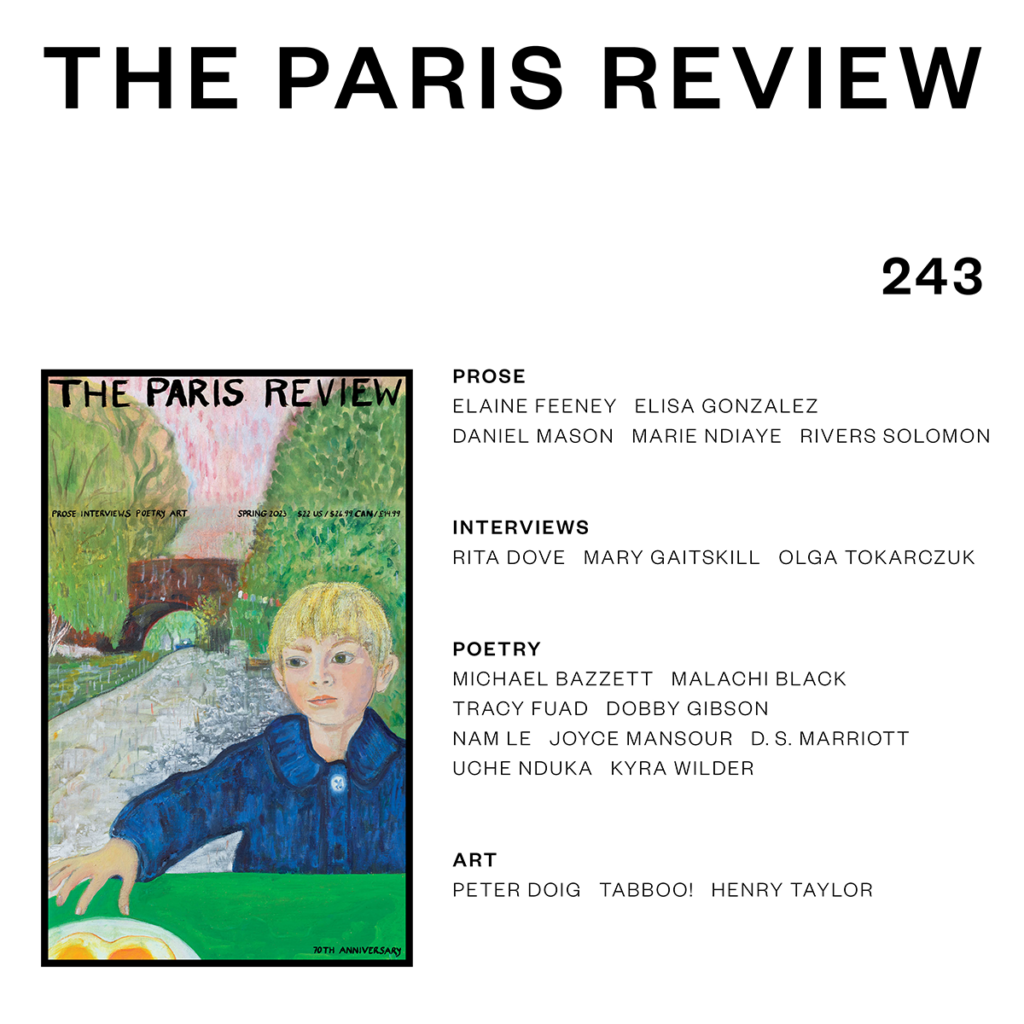

This spring rings in the magazine’s seventieth anniversary, and twenty years since the loss of its visionary longtime editor. To mark the occasion, issue no. 243 has a cover created for the Review by Peter Doig—inspired, he told us, by a birthday card he made for his son Locker—and includes not two but three Writers at Work interviews: with Dove, with the American short story writer and novelist Mary Gaitskill, and with Olga Tokarczuk, winner of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature. In many ways, though, this issue is consistent with the others in our long history, featuring the best prose, poetry, and art that we could muster, by writers and artists you’ve heard of and some you haven’t. You’ll find prose by Marie NDiaye, Elisa Gonzalez, Rivers Solomon, Daniel Mason, and Elaine Feeney; poems by Nam Le and D. S. Marriott; and artworks including a portfolio by Tabboo!, featuring paintings inspired by words he associates with the magazine (including “high falutin,” “bon vivant,” and “wreaking havoc”). We are grateful to everyone who has appeared in our pages, and to all the people who have shepherded the Review over the past seven decades, so that this one can land in your mailbox as the season turns.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/XIbPmuE

Comments

Post a Comment