Photograph courtesy of Kyra Wilder.

For our new series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Kyra Wilder’s “John Wick Is So Tired” appears in our new Spring issue, no. 243.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase?

With the first line. It was something I’d thought a lot about—I run marathons, and in those tense few days before the race, when I’m drinking water and carb loading and meditating on what’s going to happen, I watch John Wick, specifically because of the way Keanu Reeves runs. He looks so tired, but he’s winning.

In the fall of 2021, I was tapering for a marathon and then I had to go to a funeral, and suddenly my John Wick time got invaded by real grief. And John Wick was good for that, too.

What were you reading while you were writing the poem?

I was reading a lot of Ian Fleming that fall. I got pretty obsessed with the fact that he included a recipe for scrambled eggs in a James Bond story. In that story, Bond is completing some kind of mission in New York but also being really whiny about the poor quality of American eggs—to the point that he’s wandering around the city going into bodegas and criticizing them. So, it was either going to be “John Wick Is So Tired” or “James Bond Could Make You Some Pretty Good Eggs.”

Where did you write this poem?

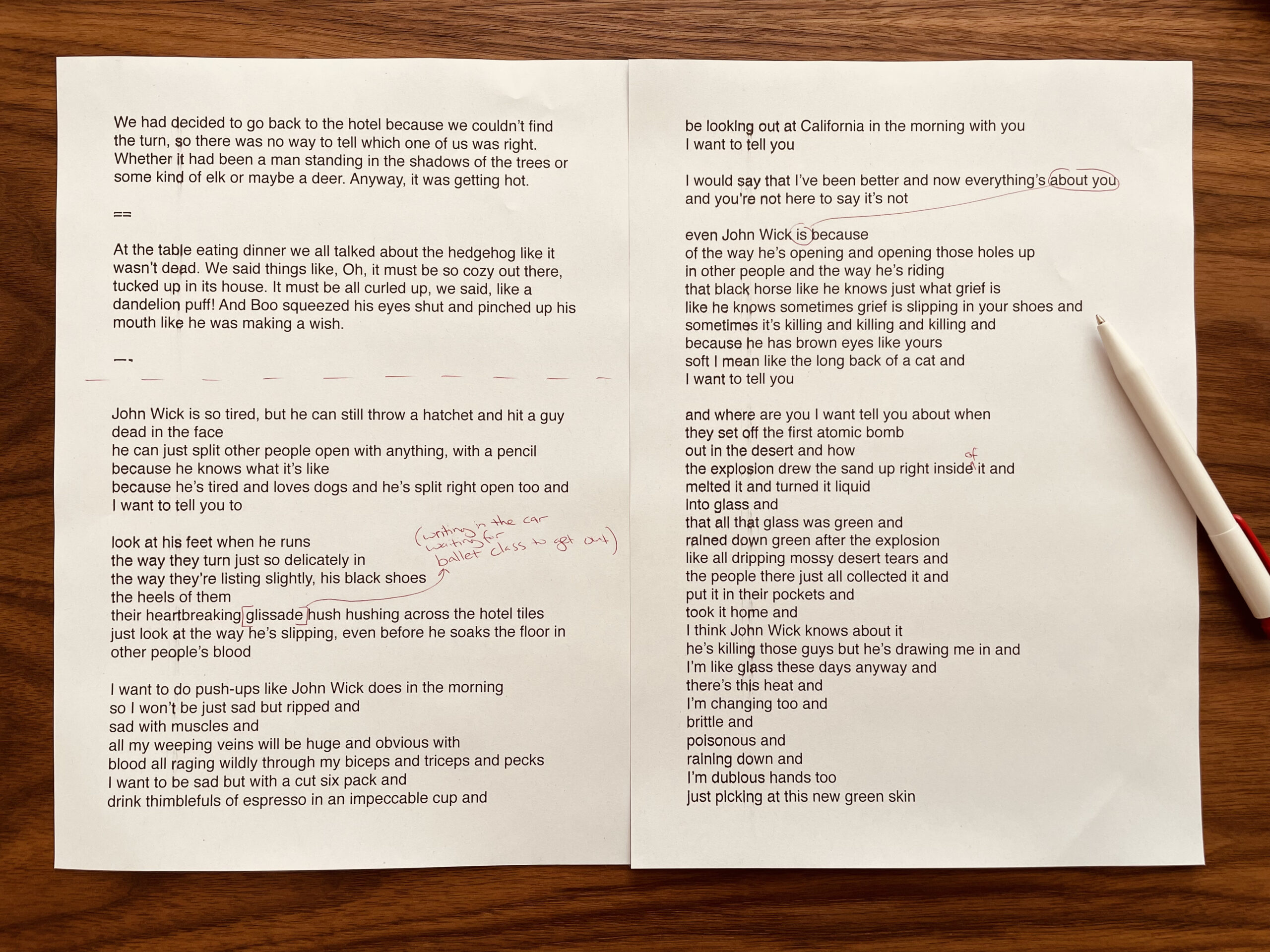

That glissade is in there because I was writing in the car, waiting to pick up my daughter from ballet class. I write all over—sometimes even at my actual desk. I have a print from Bas Jan Ader’s I’m too sad to tell you on the wall. There’s nothing better to stare at when things are going badly.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or to friends or confidantes? If so, what did they say about them?

I showed it to my husband. He’s a math guy and doesn’t read poetry, but he’s usually right about my writing. When he read the first draft, he liked the first half but said he “didn’t get” the ending. Reading that draft again now, I see what he meant.

That version was maybe more like a novel or a short story. We’ve started with John Wick, but by the end we’re lost in the desert. It’s chatty, reaching for all the conversations that are being missed—the speaker wants to watch John Wick and tell the lost person historical asides about nuclear bomb testing sites. Of course they do, but that’s for a novel. In the context of a poem, it’s too much, too close together. I’m hitting the meaning-gong too many times. John Wick (the character, the movies, the Keanu) is so good, and the poem is about this one feeling of where-are-you-right-now-how-could-you-miss-this-one-particular-thing, so we need to stay with John Wick and forget the desert.

After I found an ending that felt more specific and focused and safely clear of novel/short story/essay territory, I sent a copy to my agent, Jon Curzon. He told me he’d once made an Instagram account called Keanu Leaves, which was just full of pictures of Keanu Reeves waving goodbye.

How else did the poem change over time?

I wrote it without stanzas at first, and then decided to break up the poem following the speaker’s thoughts—where the thinking shifted, or where I thought they might pause or take a breath. The stanzas got me closer to the person speaking—they helped me hear how the speaker would say the lines.

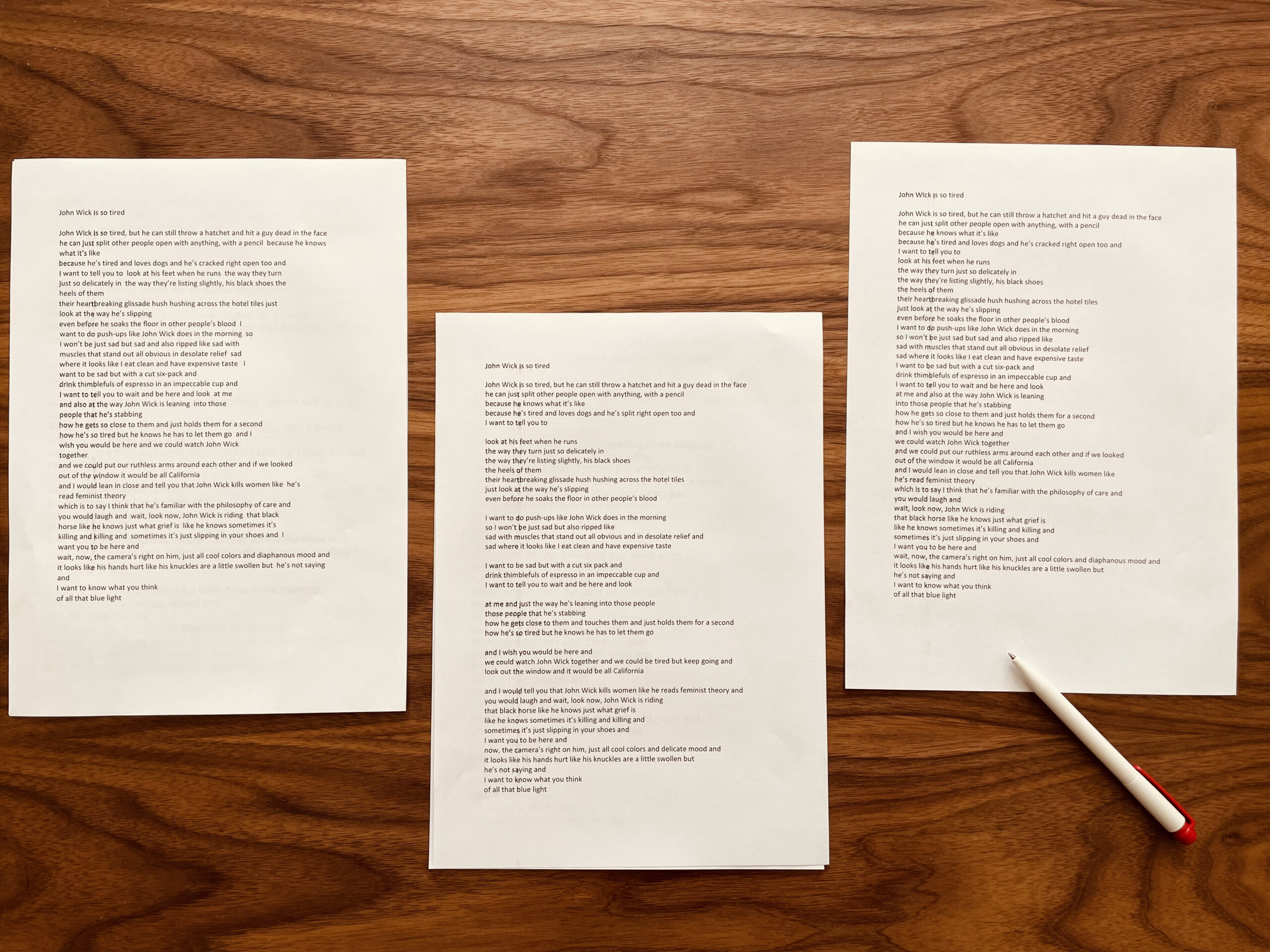

As useful as they were, though, the stanzas made the poem too dramatic. They looked like they were trying too hard. We’re starting with a hatchet thrown at someone’s face—we don’t need the additional histrionics of white space. Then it was all playing with line breaks. One of the drafts has two lines with single words. It’s not that I was thinking I might eventually end up with one-word lines—it was that I was breaking the lines up everywhere and leaving them for a while to see how they looked. I was just pushing things around, moving lines back and forth and reading it again every few days. I would open the document, break up lines, and leave it for a bit.

Once I got the poem to the point where, when I looked at it fresh, there wasn’t anything I wanted to change, I sent it off and left it for dead.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/zX7qc0f

Comments

Post a Comment