Jennifer Dunbar Dorn’s letter to Lucia Berlin from the Hotel Boulderado, September 2, 1977. Courtesy of Jennifer Dunbar Dorn and the Lucia Berlin Papers, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In 1977, Jennifer Dunbar Dorn wrote to her best friend, Lucia Berlin, from the Hotel Boulderado, where she was staying while she looked for a house in Boulder, Colorado. Her “large corner room” became “a dormitory at night,” while “during the day we roll the beds into a cupboard in the hall.” She described the hotel as a “faded red brick run by post hippies,” a place for people on the make and on the move. This might not seem like a hotel that would have had its own stationery, but it did. The paper’s crest features a lantern and mountains, and the header reads HOTEL BOULDERADO in French Clarendon font: the typeface of Westerns and outlaws, of greed, gambling, and adventure. The hotel’s name, Dunbar Dorn recently pointed out to me, “is a combination of Boulder and Colorado, obviously, but the mythic El Dorado is ingrained everywhere in the West”—its lost city of gold.

I stumbled on this letter at Harvard’s Houghton Library, where a collection of Berlin’s papers are stored in a single cardboard box. Almost everything she saved over the course of her peripatetic life is compressed into this tiny space: correspondence, notebooks, reviews, manuscripts, applications for tenure. I am Berlin’s first biographer, and I often felt deeply moved as I worked through the box last summer. Berlin is my El Dorado, and I had been looking for her for so long … Though the archivists at the library had sent me scans of some of these documents during the pandemic, it wasn’t the same as touching pages she had once touched.

As I examined the yellowed paper, placing my own thumb over the smudged thumbprint at the top, I imagined Berlin reading Dunbar Dorn’s letter at her kitchen table in Oakland after a shift on the Merritt Hospital switchboard. Mostly, it’s about Dunbar Dorn’s journey from California to Colorado with her husband, Ed Dorn, and their children. Her emphasis is on their time on the road, not on their arrival—on transience over stasis and on quest over complacency, core values of the counterculture to which she, Dorn, Berlin, and their dispersed community of writers and artists loosely belonged.

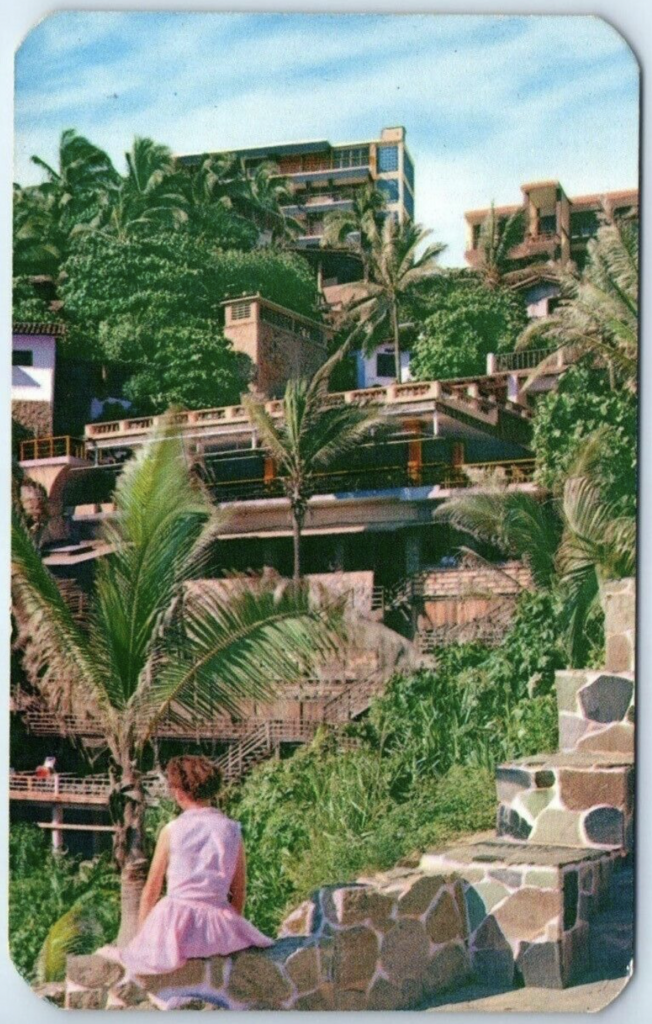

A postcard from the Hotel Acapulco, from the fifties.

The Boulderado letter stood out to me because of the paper on which it was written. I got to Harvard in the third week of a research trip in pursuit of Berlin’s scattered correspondence, and along the way I’d become obsessed with hotel stationery. The appeal, at first, was aesthetic: hotel paper is pretty, and from the forties to the seventies, it was ubiquitous across the States and Europe. A few days earlier, while wading through the papers of Berlin’s literary agent, Henry Volkening, at the New York Public Library, I’d noticed that many of his clients wrote to him from hotels. Berlin herself first used her author name on a hotel postcard to Volkening in 1961. She had just eloped to Acapulco with her third husband, Buddy Berlin, and she described her newfound happiness, signing off: “Lucia Berlin.”

But many of the hotel letters I sought out had nothing to do with Berlin’s work. By my third or fourth archive—in my third or fourth American city—I was skipping lunch breaks to call up boxes belonging to writers who I knew traveled frequently: James Baldwin, Anaïs Nin, Raymond Chandler. Here is some of what I found.

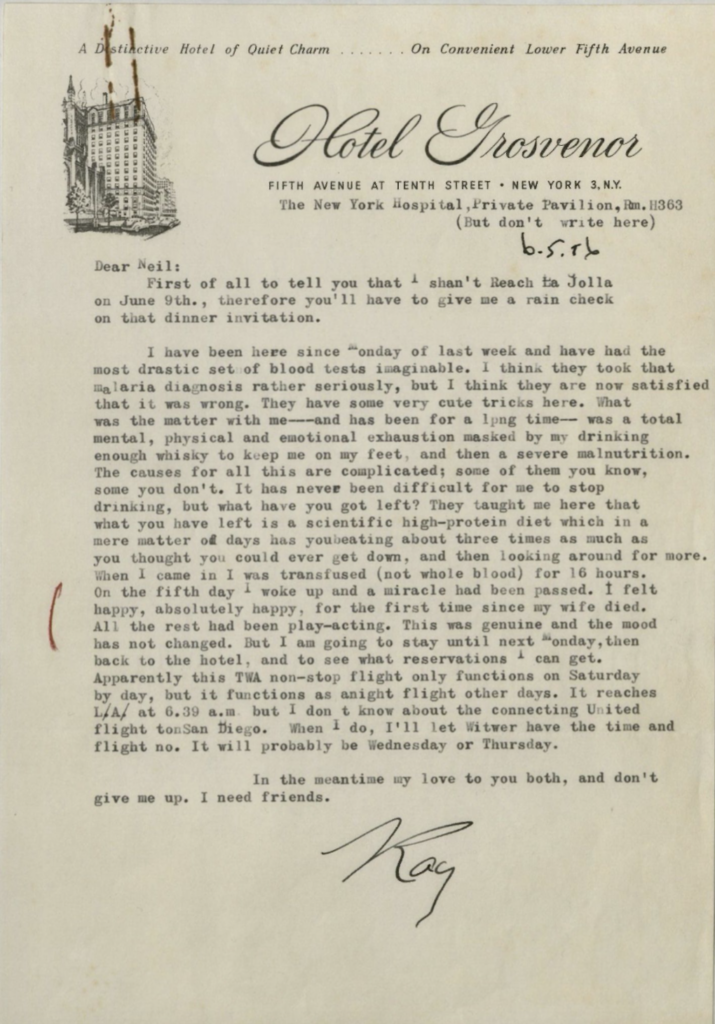

Raymond Chandler’s letter to Neil Morgan from the Hotel Grosvenor, June 5, 1956. © The Estate of Raymond Chandler. Courtesy of the Estate, c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd., 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN.

The Hotel Grosvenor

Raymond Chandler wrote to his friend Neil Morgan on Hotel Grosvenor paper in 1956, describing a recent bout of “mental, physical and emotional exhaustion” that he dealt with by “drinking enough whiskey to keep me on my feet.” At a second glance, the address on Fifth Avenue is underlined by a second one, of Room H363 at the private pavilion of New York Hospital (“But don’t write here”). Chandler wasn’t at the Grosvenor anymore; he was at the hospital, recovering from a breakdown. The hotel stationery was a respectable front for a man who had been institutionalized but who still wanted the people who loved him to know where he was. “Don’t give me up,” he ends the letter to Morgan. “I need friends.”

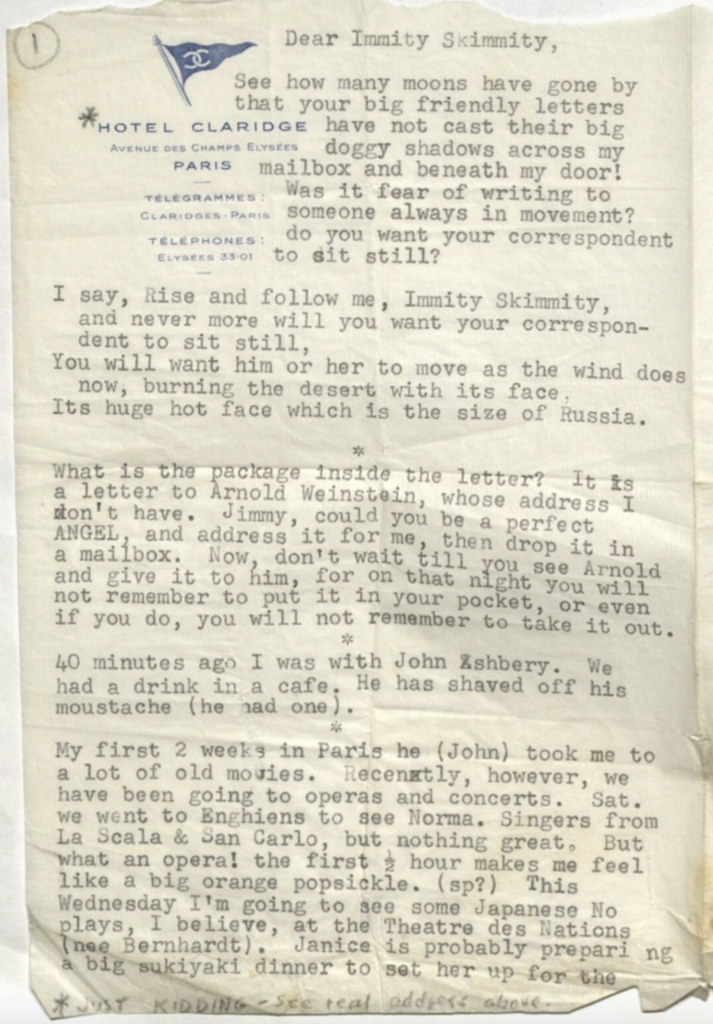

Kenneth Koch’s letter to James Schuyler from the Hotel Claridge, from the late fifties. Courtesy of the Kenneth Koch Estate and the James Schuyler Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of California, San Diego.

The Hotel Claridge

In the late fifties, Kenneth Koch sent James Schuyler a letter on paper from the Hotel Claridge in Paris, a Champs-Élysées institution and a rendezvous for “touristes fortunés,” Koch wonders whether “fear of writing to someone always in movement” is what has kept Schuyler from keeping in touch. He continues with a riff on the New Testament: “Rise and follow me, Immity Skimmity, and never more will you want your correspondent to sit still.” As it was for Berlin and the Dorns, a particular type of transience was, for Koch, a virtue. He traveled to escape the system, not to be coddled in upholstered rooms like the luxury suites at the Claridge. There is an asterisk next to the hotel crest: “Just kidding,” he adds, “see real address above.” This, it turns out, is 41, rue du Cherche-Midi, in the then hip and nonconformist sixth arrondissement, which, since the war, had become the headquarters of existentialism and bebop jazz. He must have swiped the Hotel Claridge stationery; his correspondence wears it as a costume to play a visual trick on Schuyler—to “kid.”

Gary Snyder’s letter to Shandel Parks from Timberline Lodge, July 30, 1954. Courtesy of Gary Snyder and the Gary Snyder Papers, Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego.

Timberline Lodge

Hotel stationery leaves plenty of space for editorializing. Gary Snyder wrote to Shandel Parks in 1954 from Timberline Lodge in the Oregon mountains. The hotel’s name and outline appear on the header, and at the bottom of the page there is an illustration of a ski lift, with tiny letters reading YEAR ’ROUND PLAYGROUND IN MT. HOOD NATIONAL FOREST.

Snyder explains to Parks that he has been wandering “disconsolately about,” from “the ocean beaches to the Mountains, from there to Seattle, and thence to Mountains near Canada, and back to Mountains in central Washington, and again to Seattle, and then to a stretch of beach in central Washington, wondering, always, ‘Whence?’ and ‘Whither?’” Finally, he “chanced on a job” at Timberline Lodge, “attending to the «chair lift».” He did not plan to stay long. The double chevrons around “chair lift” are a different shape from the other quotation marks in his text, as though the language of chairlifts is not his own. At Timberline Lodge, Snyder was immersed in an unfamiliar, all-American world of commercialized leisure, one he mocks with his infantilizing caption. He kept its chairlifts running, while maintaining the detachment that pervades his letter to Parks. He makes clear that as soon as the lumber strike in the Pacific Northwest is settled, he “will go to a certain crude logging camp” and “work until the snow flies. i.e. December, accumulating hoards of money.”

Back to the Boulderado

By the time Dunbar Dorn wrote to Berlin in the late seventies, the Hotel Boulderado’s stationery was informed by a countercultural aesthetic that was beginning to enter the mainstream. The whimsical logo and typography suggest that the hotel catered to seekers, dissenters, and outlaws—or to people who saw themselves as such. Guests included William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Ishmael Reed, plus a rotating cast of speakers at the University of Colorado and the Naropa Institute. In his 1975 song “Come Back to Us Barbara Lewis Hare Krishna Beauregard,” John Prine describes a hippie “buying quaaludes on the phone … In the Hotel Boulderado / at the dark end of the hall.”

And yet the hotel remained, fundamentally, a business. In the eighties, after scraping together funds to renovate, it shed its dissident aesthetic and reverted to the plush accessories and prices with which it had opened in 1908. Today, rooms start at two hundred dollars a night, and the “happenings” advertised on the hotel website include a monthly “wine club” starting at forty dollars per person. Burroughs and rollaway beds are a distant memory.

When I called the Boulderado to ask if they still print their own stationery, the front-office manager told me that they did, but that she used it for official correspondence and welcome letters to guests. Branded paper is no longer placed in the rooms. And this brings something home: no matter how closely I follow Berlin, I can never truly enter her world, because it is gone, along with the golden age of hotel stationery. What endures, of course, is Berlin’s work. In her short story “Dr. H. A. Moynihan,” originally published under the title “The Legacy” in 1982, a dentist shows his granddaughter a set of false teeth. “He had changed only one tooth,” Berlin writes, “one in front that he had put a gold cap on. That’s what made it a work of art.” I think, for her, this was a metaphor for the creative process. She does something similar with her fiction, drawing on her experience and transforming it, too, as Lydia Davis has observed. And her interventions, innovations, additions, and omissions catch the light: they’re the treasures, like El Dorado, or the gold cap on a tooth.

A prewritten hotel letter from the Mission Inn, March 14, 1946.

Nina Ellis is a British American writer and scholar. Her short stories and essays have appeared in Granta, The Idaho Review, The London Magazine, the Oxford Review of Books, and elsewhere. She won an Editors’ Choice Award in the 2021 Raymond Carver Short Story Contest. Looking for Lucia: A Biography will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2025.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2F8Djnu

Comments

Post a Comment