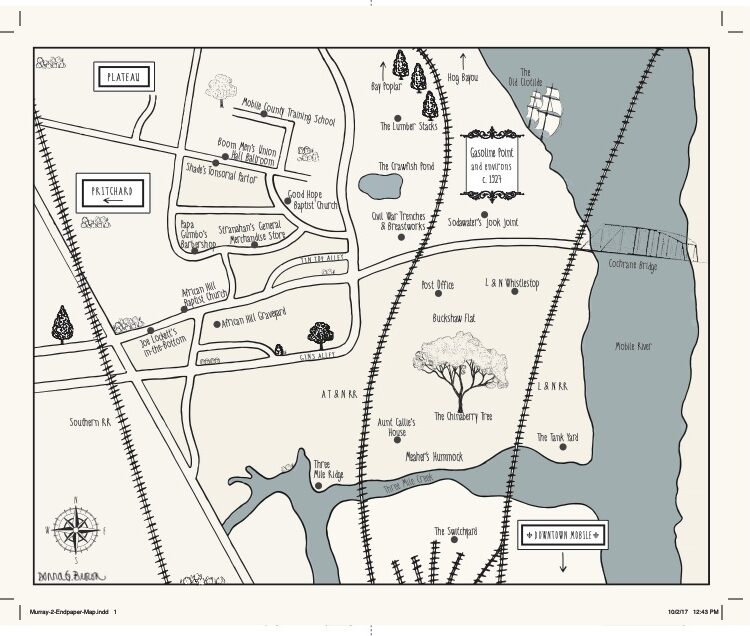

Map by Donna Brown for Library of America, with input from Paul Devlin. Based on a map drawn by Albert Murray in the 1950s or 1960s.

Circa 1969, the writer Albert Murray paid a visit to his hometown on the Alabama Gulf Coast, to report a story for Harper’s. Murray hadn’t lived there since 1935, the year he left for college. During his childhood, elements of heavy industry—sawmills, paper mills, an oil refinery—had always coexisted with wilderness, in the kind of eerily beautiful landscapes that are found only in bayou country. But as an adult, Murray was aghast to see how much industry had encroached. The “fabulous old sawmill-whistle territory, the boy-blue adventure country” of his childhood, he wrote, had been overtaken by a massive paper factory: a “storybook dragon disguised as a wide-sprawling, foul-smelling, smoke-chugging factory.” He imagined that the people who had died during his years away had been “victims of dragon claws.”

When Murray made this visit, he was in his early fifties and and was still at the beginning of his writing career. He hadn’t yet published a book. But over the next several decades, he would go on to write prodigiously, channeling into singular prose his memories of his old neighborhood before the arrival of the dragon.

The resulting work is a bildungsroman that unspools across four novels: Train Whistle Guitar (1974), The Spyglass Tree (1991), The Seven League Boots (1996), and The Magic Keys (2005). All four were reissued by the Library of America in 2018 (following a 2016 edition of Murray’s nonfiction). They share certain themes in common with other novels about boyhood, from Adventures of Huckleberry Finn to The Adventures of Augie March; but thanks to Murray’s inimitable style, and the novels’ setting, there’s nothing else quite like them in American literature.

The novels also form part of a second canon: the growing body of literature on Murray’s neighborhood, a place of historical significance in its own right. That neighborhood is known as Africatown. Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon is also set there, and several books from the last twenty years have dealt with its history more systematically.

Within a mile or so of Murray’s childhood home was a settlement created by the men and women who came to the US on the Clotilda—the last known slave ship ever brought from West African to American shores. The community was established after the Civil War, as a kind of refuge, where the exiles, along with other people of African descent who had also been freed in the war and already lived there, could speak their own languages and appoint their own leaders. It’s the only community in American history founded and governed by West Africans who had personally endured the Middle Passage. It was known in the early days as African Town, and Murray recast it in his fiction as African Hill.

When Murray was a child, Cudjo Lewis, one of the last surviving shipmates, was still a regular presence in the area (he shows up in Train Whistle Guitar as the character Unka JoJo). And around the time Murray was twelve, Hurston spent time in the neighborhood, interviewing the elderly man for what would become Barracoon—which is an autobiography of Cudjo Lewis, as told to Zora Neale Hurston.

Over the last few years, interest in Africatown has been on the rise—thanks in part to Barracoon, which was finally published posthumously in 2018. The neighborhood still survives today, and although the paper mill Murray encountered in 1969 has long since shuttered, other industrial businesses have taken its place. The residential area is blighted and poor. (“It looks like a warzone,” one of Cudjo’s descendants has remarked.) But there’s an effort underway to transform it into a destination for heritage tourism. This effort was aided by the identification of the Clotilda’s remains, in the Mobile Delta, and by the Netflix documentary Descendant, which brought international attention to the neighborhood’s plight and the recent work of its activists.

And although Murray’s books are fiction, they are also fascinating lenses into a particular time in this place. In some ways, the Scooter cycle is the best source we have for understanding the texture of life in Africatown in the early twentieth century, especially in the twenties and early thirties, when blues musicians crowded the juke joints, the surrounding forests were undisturbed, and the memory of the ship’s voyage was still palpable.

***

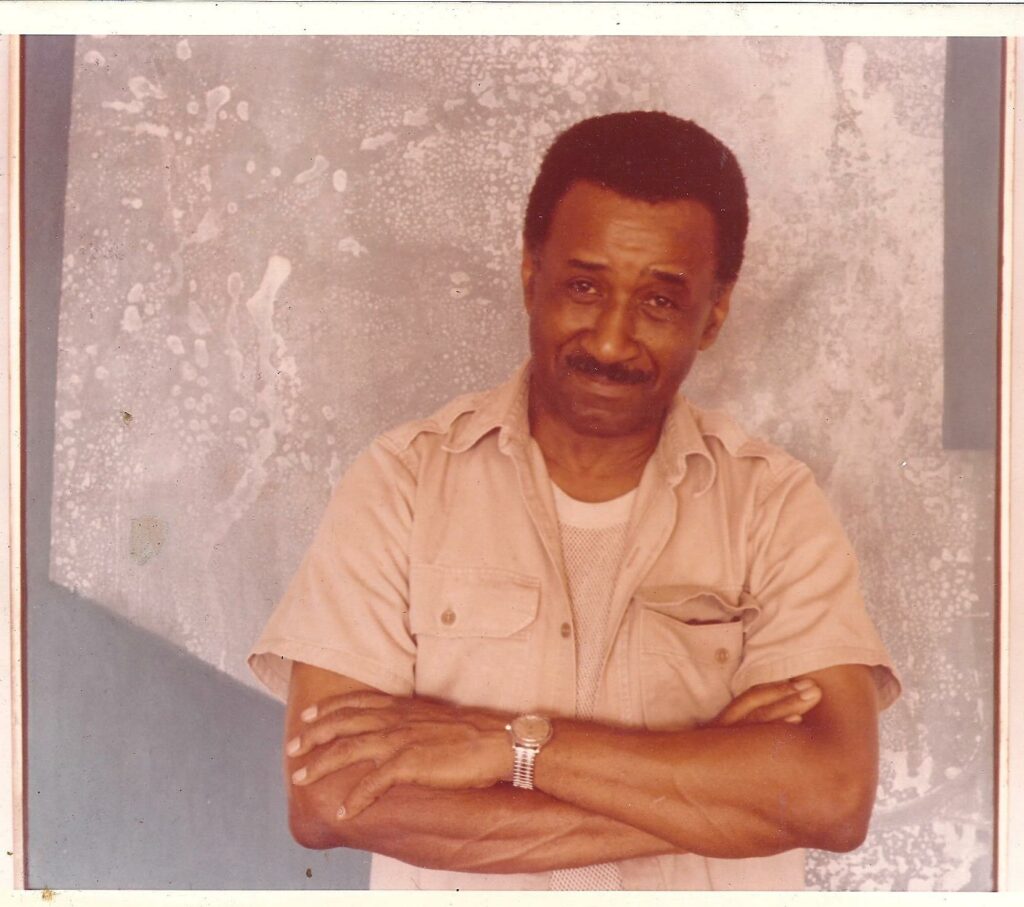

Albert Murray. Courtesy of the Murray Trust.

Scooter, the narrator and protagonist of all four novels, is obviously Murray’s alter ego—the author was straightforward about this in interviews. But the novels are more than autobiography, and Scooter is more than just a stand-in; he’s also a kind of epic hero and a trickster figure, not unlike Odysseus. Murray mixes these elements like a stride pianist, playing bass notes with one hand and chords with the other.

When Train Whistle Guitar begins, Scooter seems to be no older than ten, though he’s vague about these kinds of details. He and his best friend, Little Buddy Marshall, spend their free time traipsing around the woods and hanging out at Papa Gumbo Willie McWorthy’s barbershop.

Scooter’s family lives in a shotgun house on Dodge Mill Road, not far from Meaher’s Hummock—where Timothy Meaher, the business magnate who chartered the Clotilda voyage in 1860, was rumored to have lived. (The name “Meaher’s Hummock” is not Murray’s invention; it comes from Mobile County’s actual history. But a reader could be forgiven for thinking it’s a conscious echo of Sutpen’s Hundred, the name of the plantation belonging to William Faulkner’s most famous antagonist.) Scooter’s section of town is also home to an oil refinery and has taken on the name Gasoline Point. Train tracks border it on the east and west, and some of Scooter’s earliest memories are of hearing the rumble of the trains. He also tells us he learned to measure time by the whistles at the nearby sawmills long before he could read a clock.

Still, an element of wilderness remains intact. Our narrator is never more lyrical than when he’s depicting these rural-industrial landscapes. Take this passage from Train Whistle Guitar, where Scooter describes hopping onto a boxcar:

Then it was stopping and we were ready and we climbed over the side and came down the ladder and struck out forward. We were still in the bayou country, and beyond the train-smell there was the sour-sweet snakey smell of the swampland. We were running on slag and cinders again then and with the train quiet and waiting for Number Four you could hear the double crunching of our brogans echoing through the waterlogged moss-draped cypresses.

Up the Mobile River, north of Buckshaw Road, is the shipwreck that everyone believes is the remains of the Clotilda—or the Flotilla, or the Crowtillie, in neighborhood parlance. (Then, this was lore; now, the ship’s wreckage has been definitively identified—it seems the neighbors were right all along.) To the west of where Scooter lives, across from the AT&N railroad, is African Hill. By Scooter’s teens, most of the West Africans who once lived there have passed away, but Unka JoJo remains fairly spry. He tolls the bell every Sunday at African Hill Baptist Church and oversees the church’s cemetery. Like Scooter, Unka JoJo is an archetype; he reflects tropes of coastal Black folklore, a subject Murray knew intimately. But it’s also likely that some of the details in the narrator’s descriptions—like Unka JoJo’s “stick tapping, dicty-rocking, one-step-drag foot, catch-up shuffle walk”—come directly from Murray’s actual childhood memories of Cudjo Lewis.

According to Scooter, Unka JoJo often refers to Alabama as Nineveh and says he was brought over in the belly of a whale. Scooter tells us that when he was younger, he misunderstood the metaphor. Not knowing any geography, he thought the word Africa was short for African Hill. He assumed the references to Jonah were akin to preachers “declaring that we were all the Children of Israel on our way out of the sojourn of bondage in Egyptland.” It wasn’t until Scooter had access to a globe, in school, that he realized the old man had actually been carried over from across the world—on a 45-day journey across the roiling Atlantic, chained to the floor with 109 other captives.

***

Perhaps the most vivid character in Train Whistle Guitar is Luzana Cholly, a blues guitarist and drifter who comes back to Gasoline Point whenever he has money for gambling. Scooter and Buddy adore him: with his stories about faraway towns, his “sporty limp walk,” his “smoke-blue” voice, his guitar strings that sound like train whistles. It’s Cholly’s example that inspires the boys to skip school and climb onto that freight train, and it’s Cholly himself who hauls them back home (“as if by the nape of the neck”).

When Cholly isn’t around, the boys often park themselves at the barbershop. The men there relate anecdotes about the brothels (“sporting houses”) in New Orleans and San Francisco, and about the pimps and sex workers in Paris’s Pigalle (“Pig Alley”). The men pretend to forget Scooter and Buddy are within earshot, but it’s tacitly understood that the boys are getting an education. The barbershop is also where Scooter starts to learn the finer points of racial and class hierarchies—in particular, the differences between “high yallers” (light-skinned people of mixed race) whose parents were also high yallers, and “brand new mulattoes.”

There is also the air of latent, and sometimes outright, violence in this adult world. Hurston hinted at the dangers of Africatown in the later chapters of Barracoon. One of Cudjo’s sons was sent to prison for homicide, and after his sentence was commuted, he was murdered in front of a grocery store. Another boy in the family was decapitated by a train. The Scooter novels have echoes of these events. In one passage, a man named Beau Beau Weaver leaves the barbershop, and less than an hour later the boys hear someone screaming down the road. When they arrive, Weaver is lying in a puddle of blood, wearing only his underwear, with stab wounds all over his body. They learn that Weaver’s girlfriend caught him in another woman’s bedroom and murdered him in the yard.

In another scene, the boys are perched on a tree outside a nightclub, Joe Lockett’s-in-the-Bottom, watching the musicians perform on a Saturday night. A sheriff’s deputy comes to break up the party, and Stagolee Dupas, a piano player, refuses to leave. The deputy starts kicking Stagolee’s piano keys. The boys take off running when they see the deputy reach for his .38. The next day, the deputy’s body is found on the other side of town, slumped over the steering wheel of his car, with a bullet through his head. The Mobile Register reports that he was apparently killed by bootleggers.

***

For all of its rough-hewn qualities, the real-life Africatown, as of the twenties, was also home to one of the best African American schools on the Gulf Coast: the Mobile County Training School (MCTS), which was launched in 1910 in a collaboration between the shipmates’ descendants and other Black residents. Some of the most tender passages in the Scooter novels deal with this institution, which Murray attended from roughly 1923 to 1935. (In Scooter’s narration, it’s barely fictionalized at all—it shares the same name and resembles the real MCTS in almost every way.)

For most of Murray’s time as a student, a man named Benjamin Baker was the principal. Baker—whom Murray recast as B. Franklin Fisher in his novels—was a strict disciplinarian; the rumor on campus was that he kept a pistol in his desktop drawer. But if he intimidated students, he also inspired them. He was worldly, a sharp dresser, and commanding public speaker. When Murray was in his sixties, he writes in The Magic Keys, he could still hear Baker’s voice, telling the students to “acquit yourselves in all of your undertakings that generations yet unborn will rise at the mention of your name and call you blesséd.” Under Baker’s leadership, every teacher at MCTS had a college degree, a situation practically unheard of at rural Black schools in the South at that time. Rarely has an educator taken more inspiration from W.E.B. Du Bois’s notion of a “talented tenth,” a coterie of exceptional Black men and women who could take responsibility for racial progress. Everything about the school was designed to identify the most promising students and cultivate them as leaders.

Even more important in Murray’s life was the teacher who became the basis for his character Miss Lexine Metcalf. Miss Metcalf was always on the lookout for outstanding young minds.Scooter fondly recalls showing up early for school on a Wednesday morning, so he could have the globe and maps to himself. When Miss Metcalf looked up from her desk and saw him, she said, “How conscientious you are, a young man with initiative, and why not, because who if not you.”

“Who if not you?”—it’s a phrase that recurs so many times throughout the novels, always from the mouth of Miss Metcalf, that it seems likely it was a direct quotation from Murray’s life. This question apparently propelled the author for years afterward. Who, after all, if not him, to write his American epic?

So much does Scooter thrill at hearing Miss Metcalf call him “my splendid young man”—as she often does when he answers a question correctly, or shows special initiative—that he starts making excuses not to play hooky. By high school (in an arc matching Murray’s own), it becomes clear that Scooter is the most promising student the neighborhood has ever produced. He received a scholarship to college. He never moves back to Gasoline Point, but figures like Luzana Cholly and Miss Metcalf loom large in his imagination, long after he is gone.

Africatown on Sunday, June 2, 2019, in Mobile, Ala. Photograph by Mike Kittrell.

***

It’s been ten years now since Murray died at his home in Harlem, catercorner from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. He lived there for five decades, far longer than he’d been in Alabama or any other place. Little wonder that his name is often associated with New York.

As for his work, it’s likely his extensive writing on jazz and the blues, including the autobiography Count Basie (which he co-wrote), that gets the most attention now. His knowledge of jazz was truly encyclopedic; he co-founded Jazz at Lincoln Center with Wynton Marsalis. But to understand why he was so drawn to this kind of music as an art form, we need his fiction. Nothing but jazz and the blues captured so well the atmosphere of his old neighborhood: the overwhelming sorrow that emanated from figures like Unka JoJo, the worldliness and playfulness of the men he met at the barbershop, and the idealism of figures like Baker and Miss Metcalf.

This also speaks to his contribution to the literature on Africatown. If Hurston’s purpose, as she wrote in the Barracoon introduction, was to render a kind of anthropological report on Cudjo, to inquire about how the “Nigerian ‘heathen’” had “borne up under the process of civilization,” then it was Murray’s lot to write about the world that Cudjo and the other shipmates—along with their descendants, the American-born Blacks with whom the descendants integrated, and the power elites of Alabama who shaped the conditions of their lives—had collectively made.

Nick Tabor is a freelance journalist living in New York. His first book, America’s Last Slave Ship and the Community It Created, was published in February. Kern M. Jackson is a folklorist and the director of the African American Studies Program at the University of Southern Alabama. He was the co-writer and a co-producer of the Netflix documentary Descendant.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/1wrklIa

Comments

Post a Comment