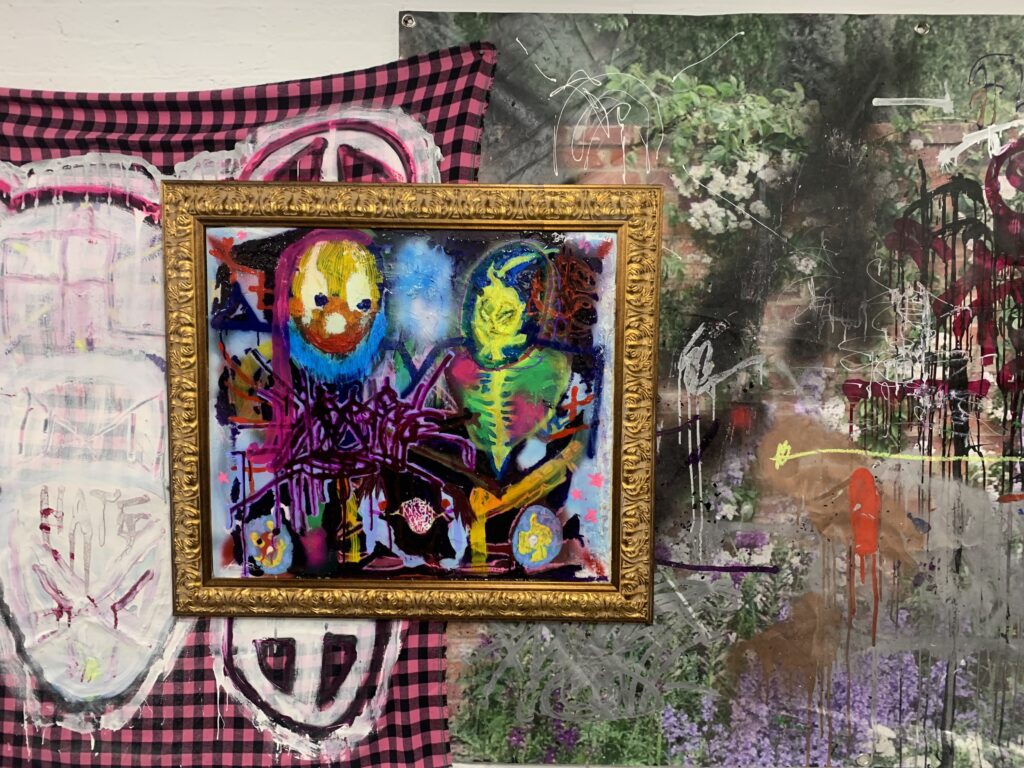

Benjamin Reichwald and Jonas Rönnberg, OCB Dinitrol, 2023. Photograph by Olivia Kan-Sperling.

This summer, we’re launching a series called Eavesdropping—which is more or less about what it sounds like. We’re asking writers to take their notebooks to interesting events or places; they’ll record what they see, but mostly what they hear. In the first of the series, Elena Saavedra Buckley goes to a TriBeCa gallery opening for an exhibit of collaborative paintings by two Swedish hip-hop artists, and surveys the scene.

The art show I was going to was risky to google, because it was called Fucked for Life and took place in the basement of a gallery called the Hole. It had been raining, and the humidity followed us downstairs, where the low-ceilinged room felt like the hull of a ship. The paintings reminded me of more focused, imaginative versions of the kind of thing your friend’s stoner older brother might make in his room—they had barely shaped demonic faces at their centers, orbited by tagged abstractions and blooms of neon, all lacquered and dripping. Some sat in ironic-seeming ornate gold frames; others hung against long stretches of loose fabric layered with graffiti, which had been made the day before and seemed to be releasing damp chemical wafts.

This was the private opening of new collaborative paintings by Bladee and Varg2 , whose real names are Benjamin Reichwald and Jonas Rönnberg—two Swedish artists affiliated with a Nordic brand of underground hip-hop that’s been gaining steam since the mid-aughts. The two collectives at its center are the Sad Boys—helmed by the fairly famous Yung Lean—and Drain Gang, which was started by Bladee. I didn’t know much about Varg2

, whose real names are Benjamin Reichwald and Jonas Rönnberg—two Swedish artists affiliated with a Nordic brand of underground hip-hop that’s been gaining steam since the mid-aughts. The two collectives at its center are the Sad Boys—helmed by the fairly famous Yung Lean—and Drain Gang, which was started by Bladee. I didn’t know much about Varg2 before this weekend; he’s a techno producer who used to go by just Varg until a German metal band of the same name sent him a cease and desist. (He then released an album called Fuck Varg.) But I love the warbling, auto-tuned, alabaster Bladee—the second e is silent—who raps as often about Gnosticism and demons as he does about weed and being depressed. He has obsessive Zoomer fans like the rest of Drain Gang, though his are made especially rabid by how difficult he is to grasp. You can barely see him from behind his hair, hoodies, sunglasses, and blasted-out photo edits; one comment on a recent music video reads, “i don’t think i’ll ever get used to seeing high quality footage of bladee,” and a four-second clip of him saying “Drain Gang”—just the audio!—has 132,000 views. He says he was once struck by lightning in Thailand.

before this weekend; he’s a techno producer who used to go by just Varg until a German metal band of the same name sent him a cease and desist. (He then released an album called Fuck Varg.) But I love the warbling, auto-tuned, alabaster Bladee—the second e is silent—who raps as often about Gnosticism and demons as he does about weed and being depressed. He has obsessive Zoomer fans like the rest of Drain Gang, though his are made especially rabid by how difficult he is to grasp. You can barely see him from behind his hair, hoodies, sunglasses, and blasted-out photo edits; one comment on a recent music video reads, “i don’t think i’ll ever get used to seeing high quality footage of bladee,” and a four-second clip of him saying “Drain Gang”—just the audio!—has 132,000 views. He says he was once struck by lightning in Thailand.

None of these rappers have become household names, but Bladee has gone from posting his songs on SoundCloud to designing capsule collections for Marc Jacobs and Gant. Are the paintings, priced at an average of ten thousand dollars (and which Bladee’s fans bemoan on Reddit for costing “1460 hamburgers”), evidence of an evaporating underground ethos? Visual art isn’t much of an artistic stretch for these two, nor is working side by side on the same canvas, as they did for these pieces. They both came up as taggers, and Bladee made the merch and promo images for Drain Gang before his work with big designers. Even his use of language feels painterly; in “Real Spring,” he sings: “White light shines towers up in gold / Hawk flies low, strikes like my pose / Three stars dance over the globe / Life unfolds, faith comes unfroze.” That’s Hilma “as fuck” Klint, I think, recalling something I read recently: that the paintings of that notoriously mystical, also Swedish artist had in fact also been made collectively—by as many as thirteen artists in total, in “a realm inhabited by a plurality of spirits.”

After their rapid laps around the room, some attendees congregated in the middle. One group of twentysomethings was talking about visiting Australia. “Don’t go,” one guy said. “It sucks.” His friend offered a defense: “You know, what’s crazy about Australia is it’s a place where animals have had so long to evolve.” “Kangaroos are descended from deer,” she said. There was some confusion about whether this was right before they pivoted to the true nature of kangaroo pouches, which is sort of the Godwin’s law of Australia 101–type discussions. “I thought there would be hair in there, but it looks like an access point to their insides,” she said. It’s actually somewhat difficult to find pictures of the pouches online; I’ve tried. This group struggled to google them. Others discussed summer itineraries, plugging their plans (Marseilles, Bermuda) or reminiscing on unsuccessful past trips (Dublin, where the only thing to do other than drink, reportedly, was spend ninety dollars on orange blossom water at the Joyce-themed pharmacy). A sliver of the floor had become slippery in the damp conditions, nearly sending many extremities into the paintings, and one woman predicted that her friend would sooner save Bladee’s work than she would her. “Save the paintings,” she said. “It’s like ‘Save the whales.’ ”

There were infantry waves of outfits. The straight couples in all black came first, the men asking the girls which paintings were their favorite and the girls shrugging in response—“the buyers,” as someone later called them. The youth followed, wearing many kinds of camo, low-rise trousers, unflattering glasses, and contextless outerwear. The most out-of-place accessory present was a Park Slope Food Coop tote bag, lugged by an affable and exhausted GQ photographer who had been following the artists around all day. Of course, there were a lot of tactical pants. The best of those, in leather, were worn by Ecco2K, another Drain Gang member, who also wore a balaclava topped with what looked like black hair from a troll doll. I wore a taupe Calvin Klein chiffon slip dress and black Tecovas cowboy boots, with—and I was not alone in this choice—a giant windbreaker, my attempt to step into the Drain Gang headspace. At one point, a girl approached me to say that she used to own earrings by the same designer as the ones I was wearing, but that her ex-girlfriend had stolen them. When I told her to buy them for forty dollars on Depop, like I did, she said that the same ex got her banned from the site.

“How does someone get banned from Depop?” I asked.

“She gave me a necklace for my birthday that had her blood in a vintage Balenciaga vial,” she replied. (Bladee, describing the concept of “drain,” has said: “Everything me and my bros do is connected to that concept—we might drain some blood for good fortune.”) Post-breakup, this girl listed the necklace on Depop, after which the ex-girlfriend reported her to the company for hawking biohazards.

“So now I can’t scalp anymore,” she went on. “My ex kept saying I was ‘the epitome of a scumbag.’ ”

“I think my feelings would have been hurt if you had tried to sell my blood,” I said, smiling weakly. She looked a little guilty. And then Bladee arrived!

I felt maternal toward him, this rapper two years my senior, who was wearing a relatively unassuming fit: black crocodile dress shoes, crinkled jeans, a plaid shirt and gray hoodie, Oakleys, and a black cap. He accepted such feelings with a boyish affect—he kept fiddling his long brown curls into a small ponytail under his chin. I remembered how sad he’d seemed on some of his most beautiful tracks, like 2018’s “Waster”: “Just running through the days, running through the pain … Sorry, Mom, I know you hate to see me this way.” Most of the feeling came from the situation, though, since standing next to one’s paintings on a wall is an inescapably childlike position. Every object becomes a macaroni necklace, every gallery a school gymnasium, every wall a refrigerator. A woman gave the artists two bouquets of yellow roses while they shuffled around the room, up and down the stairs, as the attendees quietly egged each other on to go say hi.

My conversation with Bladee and Varg2 was brief; I approached them upstairs, near the rosé station. Varg told me about the buildings they had been tagging downtown. Bladee was sweet and relaxed. We discussed af Klint—“I’m a huge fan,” he said. After spending most of the trip in a friend’s studio to prep for the show, he was leaving New York in two days for Stockholm. “It just turned to spring there,” he said, though he wondered whether he should stick around until the rain quit. “But it’s so expensive,” he said, giggling. He gets it.

was brief; I approached them upstairs, near the rosé station. Varg told me about the buildings they had been tagging downtown. Bladee was sweet and relaxed. We discussed af Klint—“I’m a huge fan,” he said. After spending most of the trip in a friend’s studio to prep for the show, he was leaving New York in two days for Stockholm. “It just turned to spring there,” he said, though he wondered whether he should stick around until the rain quit. “But it’s so expensive,” he said, giggling. He gets it.

There was a private dinner at Lucien planned for after the opening. It was funny to imagine Bladee eating food, especially leaky bistro stuff like moules frites; it’s possible he snacked at the gas station that appears in the “Obedient” music video, but he seems like a breatharian to me. Other attendees were going to a “Caroline Polachek party.” I decided to leave for a birthday at a bar in Brooklyn. Some friends had brought two bouquets of flowers for the birthday girl and boy: orange lilies and some kind of violets. That made four bouquets for the night, the two from earlier and these ones—vibrating symmetrically in two boroughs, two drops of paint folded into loose canvas to make two mirrored pairs across the river; a plurality of spirits. There is a section of a Jonathan Williams poem called “What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me,” in which he quotes John Clare: “I found the poems in the fields / And only wrote them down.” I’m not sure if those fields, where we go when we make our art, are very accessible through the underbellies of Manhattan galleries. But I do think people like Bladee go to them often, and always with their friends. That’s real spring.

Elena Saavedra Buckley is an editor of Harper’s and The Drift.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/KPpNMd7

Comments

Post a Comment