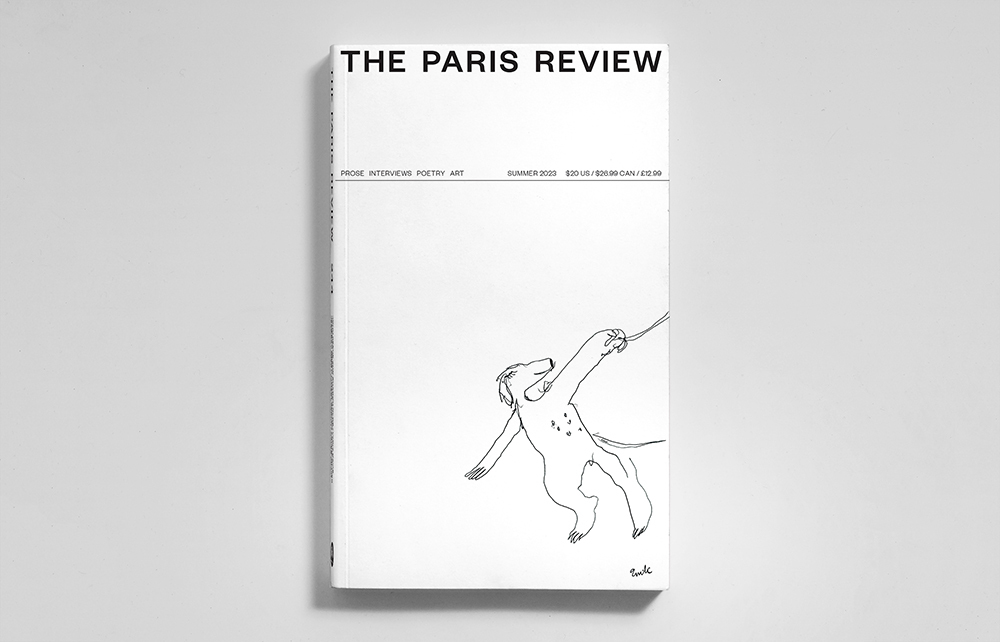

The cover of our Summer issue, online next week and on newsstands June 13, features a drawing of a dog perched on its hind legs, midmotion—so much so that she appears to be almost sliding or dancing off the page as she reaches for a leash (or is it a length of ribbon?). The first thing I noticed about the cover—besides its chic abundance of white space, which seems to beg me to spill coffee or red wine on it—was the dog’s smile. Her eyes are closed almost beatifically, and her mouth is curved in that upside-down rainbow that anyone who has ever loved a dog will recognize. This is a cover that, appropriately for summer, will bring you joy. The canine in question is London, the guide dog of our cover artist, Emilie Louise Gossiaux. Gossiaux and I chatted on the phone about her unique relationship with London, her especially tactile drawing practice, and human-animal connection.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about our cover star, London. What kind of dog is she and how long have you had her?

GOSSIAUX

She’s a blond English Labrador retriever. We will have been together for ten years in August. When she’s at home, she’s very silly and playful. She likes to snuggle a lot and rub against you. Indoors, I let her be the center of attention—she needs to say hi to everyone. But when she’s outside and working in her harness she’s very motivated and serious. She doesn’t care about other dogs or people—she’s just focused on the two of us. Our relationship is like a marriage. It took time to get to know each other’s quirks and how best to communicate, but after a couple of years, we became completely interdependent. I take care of her and she takes care of me. Now she’s thirteen years old and semiretired. Commuting to my studio in Queens is too far of a journey for her. But she still really loves working when she can.

INTERVIEWER

When did you start putting London in your artwork?

GOSSIAUX

In 2018, when I was in my second year of grad school. The vet had called to tell me that they’d found these tumors on her gums—they had to remove six of her teeth and thought she might have mouth cancer. I was beside myself, sobbing on the phone. While London recovered from the surgery and I waited for her biopsy results, we spent a week in bed, and I started making drawings of her in my sketchbook, including one of us dancing—it was of a memory from when we were younger and she and I would come back from the studio and I would put on music and she would put her paws into my hands and we’d celebrate another day of work and being home again. In the end, she was totally fine—it was just a bad gum infection—but I wanted to create a monument to her, so I made a sculpture called Dancing with London. First I built a base for her body with polystyrene foam, then I carved it away to shape it, and I layered papier-mâché over that—CelluClay, a paper-pulp mixture. When it dries, it’s very, very strong, like stone.

Photograph by Scott Rossi.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder if there are many monuments to dogs out there …

GOSSIAUX

I haven’t seen any, except for the Balto statue in Central Park.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve made many drawings of London since then, including the one on our cover, London with Ribbon. Can you tell me about that ribbon?

GOSSIAUX

That drawing is a detail of a larger work called London, Midsummer, which features three Londons, each holding a red ribbon that looks like a leash and dancing around a Maypole that resembles my white cane. In this joyful dance London is very much in her own body—it’s a celebration of nature. The drawing is partly about coexistence of animals and humans, but it’s also about autonomy. One of the things we don’t usually think about is how dogs and other animals have agency and emotions—we don’t own them. I like to let London roam around in my imagination so that, when I draw her, her personality comes to life.

INTERVIEWER

What is your drawing process like?

GOSSIAUX

It’s a very tactile experience. I use something called a Sensational BlackBoard, which is basically a plastic sheet that has rubber padding on top of it. When I put my paper over the pad and press into it with my pen, it raises up the line that I’ve drawn. At the same time that I’m drawing a line, I’m able to feel it with my other hand. That’s why I work so quickly and simply; I really don’t take my pen off the paper. It’s blind contour drawing—literally. I draw very quickly so I can get the image from my mind down on the page as fast as possible—the one on your cover took maybe five minutes. But I’ll sit in front of a blank page and meditate on it for about ten minutes before I start, to map out the drawing before I put my pen on the paper.

I’m touching the paper, feeling its size and imagining it in front of me. I can already see the line drawing I want to make—the action that the London in that drawing will be performing—as well as the mood I want the picture to have. I gather up all that energy and I let myself feel it emotionally, too. And that’s when I start to draw.

I like to make multiple drawings at a time because sometimes I’ll finish and think, No, that doesn’t really quite capture what I’m seeing in my mind. Or sometimes I’ll make little mistakes and want to redo the picture—but then I’ll go back and end up enjoying the mistake.

Photograph by Scott Rossi.

INTERVIEWER

How is the process of sculpting different?

GOSSIAUX

What I like about drawing is that it’s so immediate. It always feels like I’m discovering something about the piece that I’m making. The process with clay is much slower. You can’t rush it—the clay has to dry before you can build with it—but you also have to maintain a balance of wetness and hardness as you work. I take it one step at a time, like with drawing, only slower—building a leg, then a torso, then an arm.

INTERVIEWER

What are you working on right now?

GOSSIAUX

I’m on a residency at the Queens Museum, which will end with a solo show that opens on October 22, for which I’m making a large installation based off of the same drawing, London, Midsummer. There will be three human-scale sculptures of London holding ribbon-leashes and dancing around a Maypole that looks like my white cane, and high-relief murals of trees on the walls around it. The Maypole is going to be fifteen feet tall, and the London sculptures will be five feet—my height.

Photograph by Scott Rossi.

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/Rf7blzX

Comments

Post a Comment