Not long ago, during a spring clean, I came across one of the dozen or so notebooks in which I’d been keeping a diary back in 2020, and found myself sitting on the floor to read. I was expecting the writing to be disappointing (it was) and that I’d feel a mixture of embarrassment and exasperation at my repetitive thought patterns (I did). I was more surprised to realize that, having faithfully kept a near-daily record of my life during one of the most eventful periods in recent American history, what I’d written was almost exclusively about cars, and my monthslong efforts to buy one. “B. offered to drive me to see the Yaris,” a typical passage begins. “I brought water, pears, chocolate, cigs. Talked about cars all the way. He seemed subdued.” Another entry, in an apparently unconscious tribute to Daphne du Maurier, opens: “Last night I got into Volvo C30s again.” There are accounts of test drives: “Driving the automatic: never quite being able to tell if it is off or just v. quiet.” And moments of reflection: “S. sent me a picture of his pickup and many planks of wood. Jealous of male agency.” And then, in the middle of one September entry: “Mum asked if I had spoken to shrink about the car issue.”

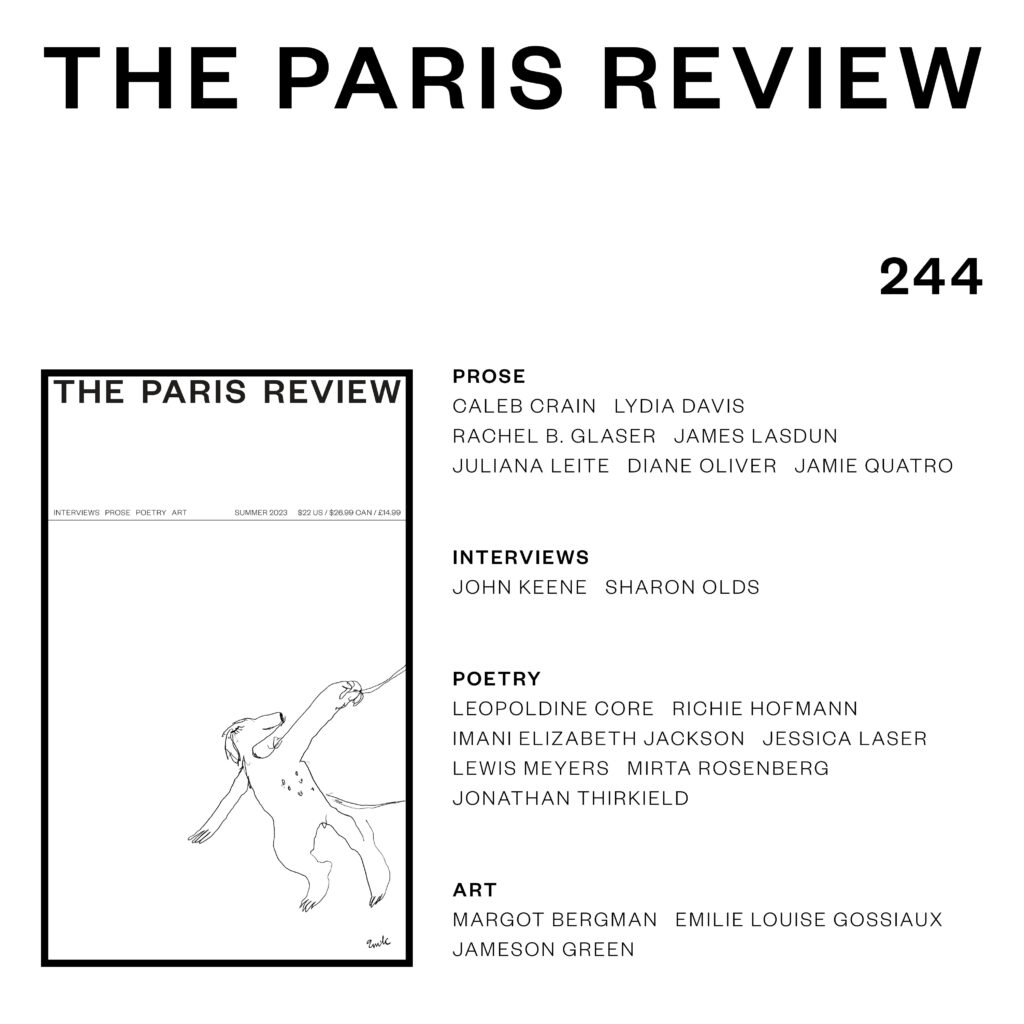

We at the Review take an especial pleasure, as readers, in the diary form: that peculiar mixture of performance and unwitting self-revelation, of shapelessness and obsessive (occasionally deranged) selectivity; that sense of a narrative unfolding in real time, almost without the author’s permission. And while the Review doesn’t do themes, as we were putting together our new Summer issue, no. 244, it was hard not to notice our partiality peeking through.

In the issue, Lydia Davis shares selections from her 1996 journal, and they often read like warm-up scales for her exquisitely off-kilter stories. (“For lunch—a huge potato and a glass of milk.”) You’ll also find masterful uses of the diary as a fictional device. The Brazilian writer Juliana Leite’s “My Good Friend,” translated by Zoë Perry, is an elderly widow’s apparently unremarkable Sunday-evening entry—“About the roof repair, I have nothing new to report”—that turns into a story of mostly unspoken decadeslong love. And James Lasdun’s “Helen” features excerpts from the journal of a woman who lives in what the narrator describes as a “state of incandescent, almost spiritual horror,” and whose crippling self-consciousness doesn’t protect her from humiliations the reader can see coming.

Also in issue no. 244, John Keene, in an Art of Fiction interview with Aaron Robertson, describes how blogging heralded his recovery as a writer after losing drafts of several of the stories that eventually became Counternarratives. And Sharon Olds, in an Art of Poetry interview, tells Jessica Laser about the need to keep one’s art and biography separate, especially when they are clearly not. Keeping a diary might be therapeutic, Olds explains, but “writing a poem to understand yourself better would be like making a cup with no clay, or maybe like having the clay but not making the cup.” She concludes, “If I had to choose between a poem being therapeutic and it being a better poem, I’d want it to be a better poem.”

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/zEAtvno

Comments

Post a Comment