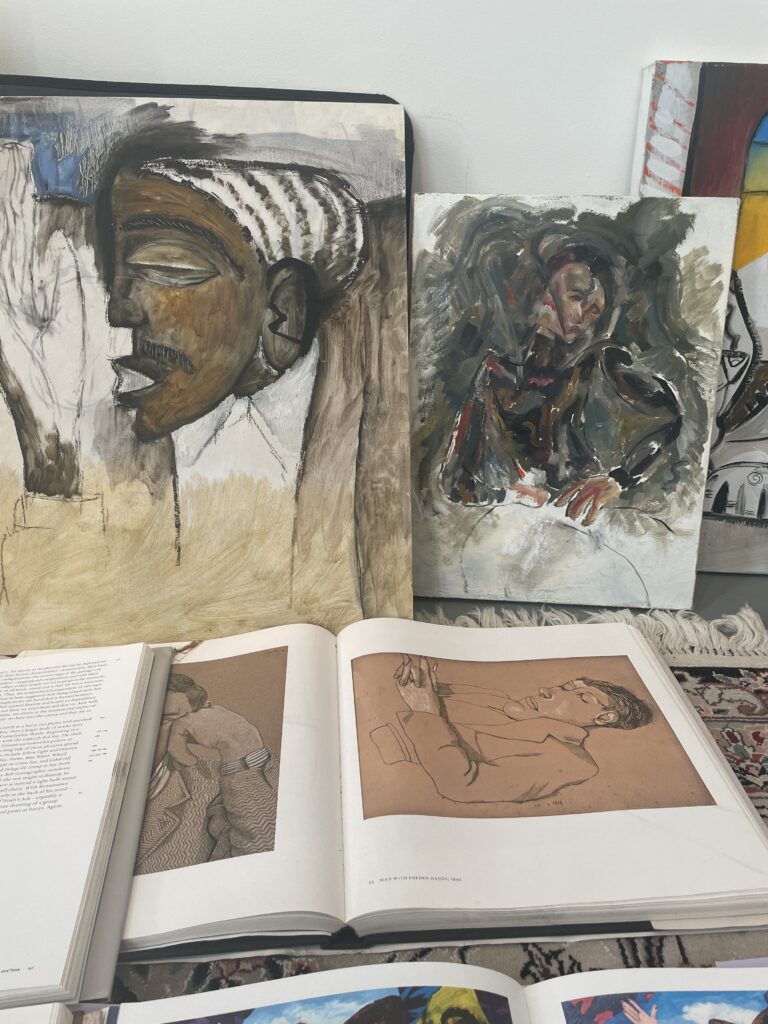

In Jameson Green’s studio. Photograph by Na Kim.

Earlier this year, the Review commissioned the artist Jameson Green to paint a series of writers’ portraits for our Summer Issue—an idea Green came up with after looking through our archives and being particularly intrigued by a portfolio of Picasso’s drawings published in 1987. What he gave us is a delightful collection of what he calls “head studies,” renderings of famous writers from our archive—some recognizable, some less so—that capture, loosely, something of each subject’s essence. And, like much of Green’s other work, Writers borrows from various art-historical styles—you’ll find, for instance, a Picasso-esque Percival Everett (or is it Edgar Allan Poe?) and Shirley Hazzard in the style of Vincent Van Gogh. Over the phone, we talked about his childhood obsession with cartoons and about the special attention portraits require, and I tried to guess who was who.

—Camille Jacobson, engagement editor

INTERVIEWER

Do you consider yourself a portraitist?

GREEN

I don’t paint portraits regularly. But when I was learning to paint, I studied artists like Alice Neel and John Singer Sargent closely. They’re very different stylistically, but there’s a relationship in terms of their sensitivity to the humanity of the sitter. Those are people I call genuine portrait painters—people like them and Diego Velázquez. The overall essence of the people he paints feels real. You need to have a special kind of attention to that essence to be a great portrait painter. I can get it on some occasions, but not always.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever painted someone you know well?

GREEN

Not in a portrait sense. I think a portrait is based on a singular sitting. I have painted my wife on multiple occasions where she has served as a character or has inspired one. So many of the figures in my paintings are theatrical, both in their presentation and their function. They’re more like actors on a stage than they are unique individuals. I’m more interested in the people in my head than I am in the people in my life, when it comes to making something.

INTERVIEWER

So how about the writers you painted for the portfolio for the Review? Are all of them real? I’ve been trying to do some guessing. Is that Edgar Allen Poe, with a raven on his shoulder?

GREEN

I don’t really remember. While I was working, I flipped through old books and old issues of The Paris Review, and looked at images of different writers. Sometimes someone would strike me, and I’d think, Oh, they could be fun to paint. Even then, I didn’t really use the writers’ photographs. That’s why I called them “head studies” and not portraits. A portrait requires some level of delicacy in terms of intention. You serve the sitter—to a degree, at least. You are playing with their likeness, but in a lot of ways it’s sensitive to the person involved. In this case, I was serving the paintings.

Photograph by Na Kim.

INTERVIEWER

Can you tell me a little bit about the styles of the head studies?

GREEN

I was thinking a lot about the paint application in Picasso’s late paintings. He was using house paint and very, very fluid oil paint applied quickly. I was trying to understand how to work with that level of thinness. Normally my brushstrokes are meatier and more evident. This time, I was using a very thin application of really wet paint. It was a wet-on-wet process, bringing down a thin tone that was already rich and solvent, and then bringing in a limited number of colors to build on the form. I was allowing myself to paint over things, to move them out of the way. I’ve kept up this process, even after finishing the series for the Review. Before making these portraits, I typically used charcoal to draw a preliminary sketch, and then I would paint in response to it, on a dry surface. Now, I’m doing everything on a wet surface, which means I have to move at a particular pace to react while it’s still wet.

INTERVIEWER

How long did it take to make these?

GREEN

I would say it typically took me only about an hour to make one. Once, I did seven in one day. In the end, I painted close to thirty portraits. But some of them were completely not of writers at all. I would think, Okay, I like how I did this one—I’m going to do another one and I’m not going to act like it’s a person at all, it’s just going to become my own thing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you remember the first things you were interested in drawing?

GREEN

I drew my own cartoons. I would make up characters based on my classmates when I was younger. At school, I put my own comics out in the classroom for people to read. I drew everything, all the time. I drew on scrap pieces of paper and often got in trouble for it—my dad complained that he couldn’t put anything down around me, because I’d start scribbling on the corners of his mail, on important receipts. But my mother preferred that to me drawing on the walls in my house.

Photograph by Na Kim.

INTERVIEWER

How did you develop your style? Who were some of your influences?

GREEN

When I was first in high school, I didn’t know much about artists. I knew about Jacob Lawrence, because my aunt had a few prints of his work, and I was interested in older illustrators— people like Norman Rockwell, J. C. Leyendecker, Maxfield Parrish. I looked at these illustrators as being at the top of the mountain of technical control.

Then I got my hands on a book of Picasso’s work from one of my friends, who said, “Look at what he was doing at our age.” I was always really competitive, so naturally I thought, Well, he can’t do better than me—I have to figure this out. That started my deep dive into different visual languages. I began paying attention to the haptics of drawing and trying to really understand the nuances of how a line can make you feel. I explored different styles and approaches because I wanted to be able to have those tools in my back pocket. Personally, I don’t care about getting too close to another artist’s wheelhouse. I’m from the school of Picasso, where if you like something and you respond to it, you steal it. I had this musical analogy in my head—I had been taught, You have to learn the scales so that if you ever come to a moment of improv, you can act without thinking.

INTERVIEWER

Do you listen to music when you’re working?

GREEN

I usually have a handful of songs for each painting that I’ll listen to on repeat. When I was working on the portfolio for the Review, because I was exploring different paint styles, those choices all based on rhythm.

My family is very musical—my mom was a music teacher, and my brother is a composer and a violin instructor. My younger sister just finished up at Yale, where she was part of an a cappella group. I, on the other hand, was cool with mostly just listening to music. But having that background has affected how I see colors and responded to imagery. Images, to me, always had a sound. When I make a painting now, it’s like the image gets shaped through a sound. It’s like I can listen to music coming into my head, and the color and form and composition start to animate themselves right before I put them on the canvas.

Photograph by Na Kim.

INTERVIEWER

How many paintbrushes do you have?

GREEN

I am not the cleanest person. I’ve seen artists who are very organized with their brushes, and take very good care of them, as they should. I don’t. My brushes are often left in some solvent, and they become pretty crappy pretty fast. I have quite a few of them, maybe thirty—though compared to other artists whose studios I’ve visited, that’s not very many. But the thing is, you get all these brushes and you end up using only ten of them.

Photograph by Na Kim.

Camille Jacobson is The Paris Review‘s engagement editor.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/pXvdGME

Comments

Post a Comment