Joxemai, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Julian Maclaren-Ross’s 1947 novel, Of Love and Hunger, is a defiantly unedifying English comedy about a vacuum-cleaner salesman trying to keep his chin up in the gloom of prewar Brighton. Its not-quite-forgotten (if never-exactly-acclaimed) author has been on my radar ever since I learned that he was the model for the bohemian novelist character X. Trapnel in Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time. That monumental roman-fleuve of English life happened to be a significant inspiration for a project of my own—a novel about the seventies London I grew up in, an excerpt of which appears in the new Summer issue of the Review—so when I found myself trying to think of a book that one of my middle-aged characters might have read in her youth, the Maclaren-Ross novel sprang to mind, and I finally read it. As it turned out, I don’t think my character, a tortured soul who tends to find everything “ghastly,” would have enjoyed it. She would have found the seedy boarding houses and tearooms and pubs that comprise its setting “ghastly”; she‘d have found the petty swindling and debt-dodging antics of the protagonist and his fellow salesmen “ghastly,” and she’d have found his unapologetic romance with the wife of an absent colleague “too ghastly for words.” But I couldn’t get enough of it. There’s nothing obviously brilliant about the writing or plotting, both of which tend toward the studiedly humdrum. (“Two more cars passed, then a bus.”) But somehow its little throwaway visions of fleeting bliss snatched from abiding squalor got under my skin. I haven’t enjoyed a novel so much in ages.

—James Lasdun, author of “Helen”

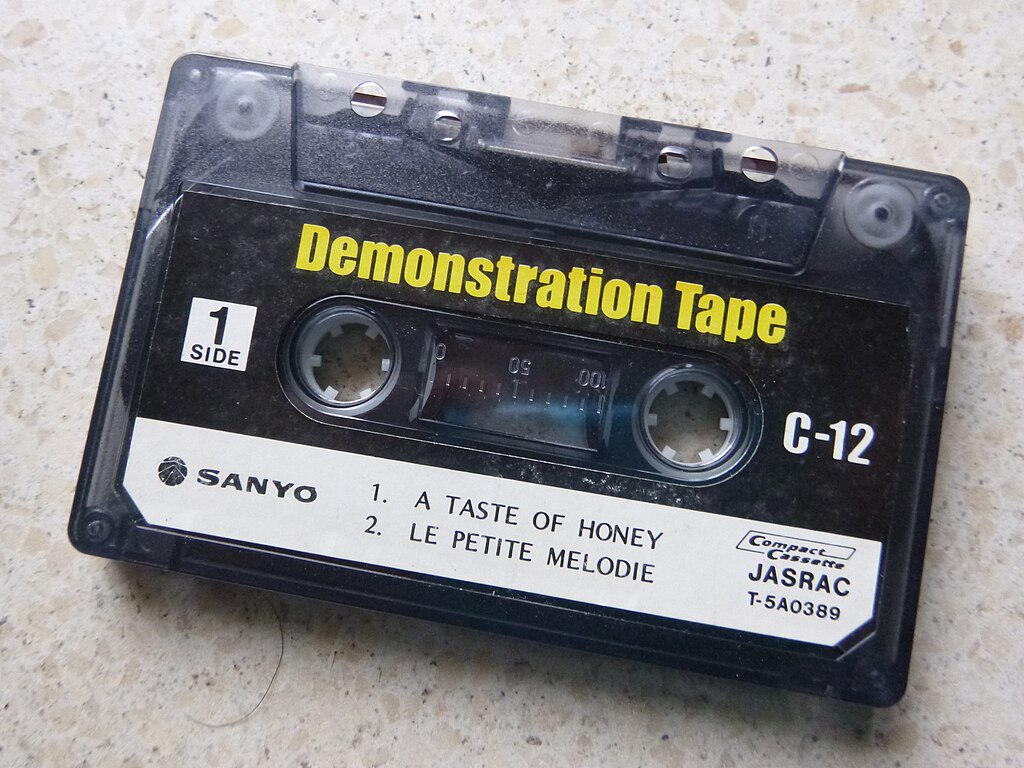

I asked my musician friend JJ Weihl why so many analog demos sound like they were recorded at the bottom of the sea. She told me that if they’re recorded on a cassette there’s “far less frequency range—everything sounds warm and muffly.” She described something she experiences sometimes called demo-itis, when she gets so attached to the demo that it’s hard to recreate it later: “chasing the blurry undefined feeling,” she said.

Recently, I’ve been listening to old demo tapes by the Cure on repeat. I like hearing the rough and sometimes fragile beginnings of their songs. A demo feels more like it’s breathing—it’s not fixed. It has been through fewer hands and there’s something enthralling about that. The song is still thinking. The demo for “Six Different Ways” sounds underwater but the essence is there—maybe even more than in the finished song. There is a thinness, a wobbliness, and a directness to the recording—a distinctly temporary quality—not perfection—not in tune always. More the act of making a root.

My dog likes this instrumental demo of “Pictures of You”; he falls into a deep relaxed sleep whenever I play it. Robert Smith’s voice is there even when it’s not. Every performance of that song seems to have its own persuasive life force. Maybe more than one can be the one.

—Leopoldine Core, author of “Ex-Stewardess”

“My buckle makes impressions / on the inside of her thigh,” begins a Tyler Childers love song in which no one’s pants come off. “If I’d known she was religious / then I wouldn’t have came stoned,” he continues, and who wouldn’t forgive his honest mistake? He’s clearly hell-bound (“working on a building out of hand-hewn brimstone,” he sings in “I Swear (to God)”), until another song has him wondering whether God might let “free will / boys mope around in purgatory,” a place he describes as “a middle ground I think might work for me.” “Born Again,” which he has called “a redneck commentary on reincarnation,” repeats the phrase “once I was” (“a dying breed,” “a broken heart”), until it becomes simply: “once I was / and you were too.” It’s as though the clause thought it needed an object to become a full sentence, before realizing, in its journey toward enlightenment, that it was already complete.

In high school on the South Side of Chicago, I would say things like “I’ll listen to any music, just not country,” as if country were the only sure marker of bad taste, probably because of an unnamed association I had made, or that had been made for me, between the genre and white ignorance, unexamined patriotism (it is called “country,” after all), guns, Christianity, and the confederacy. In adulthood, I covered my burgeoning love for country music with the safer, cooler, more presentable term Americana. Until I fell for Childers, I didn’t see that term as a euphemism.

“As a man who identifies as a country music singer,” Childers said in his acceptance speech for the 2018 Americana Music Honors and Awards’s Emerging Artist of the Year, “I feel Americana ain’t no part of nothing and is a distraction from the issues that we’re facing on a bigger level as country music singers.” In 2020, he released Long Violent History, an album of old-time fiddle music accompanied by a six-minute YouTube statement in which he speaks directly to his “rural white listeners.” He asks them to “stop being so taken aback by Black Lives Matter: if we didn’t need to be reminded, there would be justice for Breonna Taylor,” and to “start looking for ways to preserve our heritage outside of lazily defending a flag with history steeped in racism and treason.” His most recent record, Can I Take My Hounds to Heaven?, does some of that heritage-preserving. It is a triune gospel album that plays the same eight songs three different ways—an acknowledgment of tradition, and that things change.

—Jessica Laser, author of “Kings”

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/8uWQ53C

Comments

Post a Comment