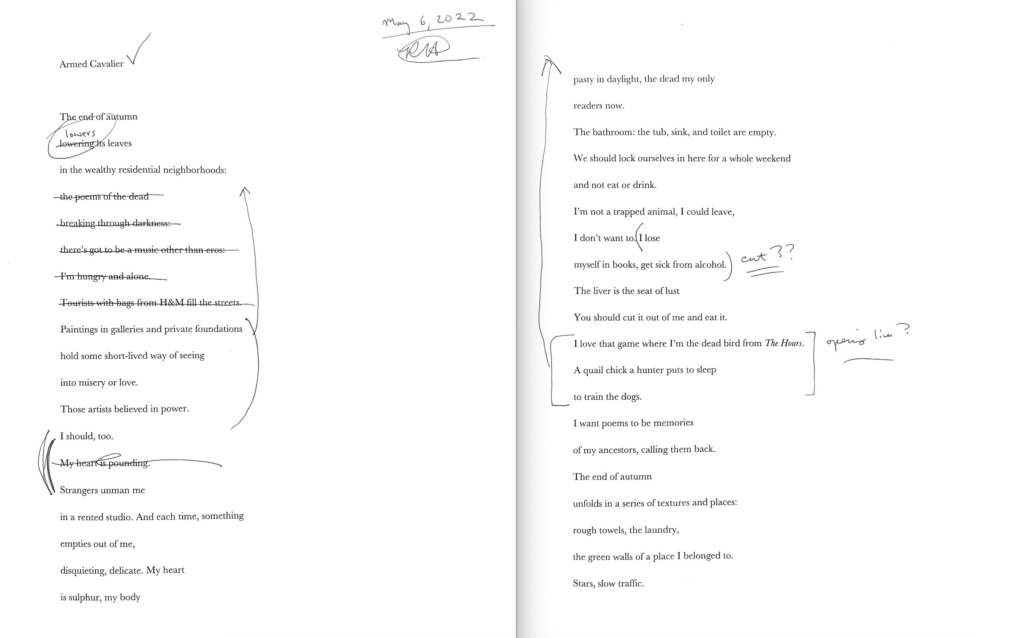

A draft of the first two pages of “Armed Cavalier.” Courtesy of Richie Hofmann.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking some poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Richie Hofmann’s “Armed Cavalier” appears in our new Summer issue, no. 244.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

As is so often the case for me, the poem began as another poem entirely. I was working on a poetic sequence that interposed my translations of Michelangelo’s homoerotic sonnets with several short, original haiku-like poems inspired by Robert Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids. Both artists were interested in beauty and torture. Mapplethorpe’s photographs are experiments in self-portraiture and bondage. In one of Michelangelo’s sonnets, the speaker confesses that, in order to be happy, he must be conquered and chained, a prisoner of an “armed cavalier” (the phrase puns on the name of the object of Michelangelo’s infatuation, Tommaso dei Cavalieri). Upon reading that phrase, I instantly wanted it to be the title for a new poem that would express the extremity of sexuality and the extremity of making art.

From the sonnets of Michelangelo, I wanted to import a kind of violence of rhetoric (not unlike the dramatic conceits we find again and again in Petrarch). The poems are so desperate. Their pain is sculptural. From the photographs of Mapplethorpe, I wanted to import a violence of image. And the sense that everything—flowers in a vase, classical sculpture, BDSM—is part of a landscape of embodied beauty. Ultimately, as I revised the poem, and reworked it into “Armed Cavalier,” I wanted to express the ferocity of feeling in both artists’ works, but without any overt ekphrastic framing.

Are there hard and easy poems?

Yes. I love the easy poems, poems that reveal themselves immediately, that feel heard and merely transcribed and not labored over thanklessly. It’s hard to love the hard poems back. I have often found, as in the case of this poem’s origin, that sometimes the best revision of a draft is the writing of a new poem.

Was “Armed Cavalier” hard or easy, then?

This was an easy one. As an exercise, I sometimes try to write in a sort of frenzy, to fight against my tendency toward elegance. Writing quickly, without pressure, allows me to encounter ideas and feelings I wouldn’t find acceptable or worthy or complete enough in my normal, judgmental mindset. I’m trying to let more of myself in to the poems—more ugliness, more hunger, more insight. This is how I drafted “Armed Cavalier.” I knew early on that it would be an important poem for me.

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends or confidants?

I show most of my drafts to other poets. Soon after I drafted this poem, I called my poet friend Christian Gullette and he helped me edit it into its final form: cutting some “tourists,” for instance, and getting right to the “galleries.” Later in the process, I called Kara van de Graaf and we agonized over two small but essential decisions: should a line read “I don’t want to” or “but I won’t”? And should the final line—with attention to grammar but also to voice and music—read “I sleep only in this bed now” or “I only sleep in this bed now”? Thank God for friends who care about this stuff!

When did you know this poem was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished after all?

A poem feels finished when I can’t enter it again. Everything falls into place, each line feels balanced and complete, the shifts between lines and sentences feel shocking but also permanent and incapable of change. This poem is finished. I have to make something new. I have to be a different poet.

Michelangelo, The Punishment of Tityus, 1532. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/yUACD59

Comments

Post a Comment