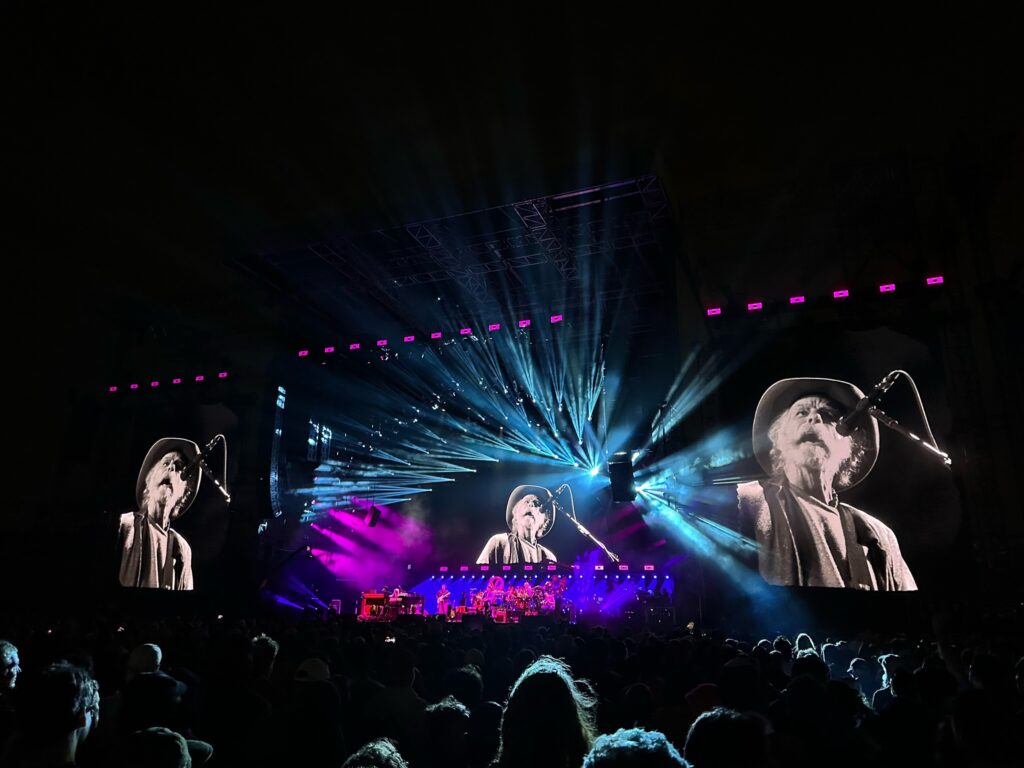

Black-and-white Bobby. Photographs by Sophie Haigney.

Let’s start with the dark stuff. On Saturday night in San Francisco, after the second-to-last-ever Dead & Co. show, every single ATM near the ballpark was apparently out of cash, because people couldn’t stop buying balloons filled with nitrous oxide, huffing them on the street for just a few more seconds of feeling high. The bars nearby were overrun, quite literally, long after everyone should have been at home. People go down at shows—it happened right in front of us one night, the medics rushing in and carrying someone out. There are, not infrequently, overdoses. There is too much of everything, sometimes. “I’m at that point in a bender where beer isn’t really doing anything for me anymore,” I heard someone joke on day three of the three-show run.

It is not that easy to drink yourself to death, actually, which I know because I have watched a lot of people try, but I could imagine it happening to many people in the context of the long slide of years or decades spent following the band. I always think “There but for the grace of God go I,” and I really mean it. So many people are dead and gone, among them the Dead’s lead songwriter, guitarist, and singer Jerry Garcia, who was killed by his own addiction to heroin at the age of fifty-three. “Do you think of Jerry as a prophet or a saint?” my friend asked me on Sunday as we got ready for the last show ever. The mood was elegiac, though the fact of finality wasn’t really sinking in, which might be why we kept repeating it over and over. “I can’t believe it’s really the last one,” someone said, not for the first time. “What are we even going to do next summer?” my friend lamented. “Are we going to like … have to get really into Phish?” “We are NOT getting into Phish,” someone else insisted, though we all agreed we would probably go see Phish at Madison Square Garden in August.

We put on our last clean Dead T-shirts—we were all running low and trading with one another—and headed back to the ballpark. A few of us had decided last minute to upgrade our tickets so we could be on the floor. I had never been on the floor for a Dead & Co. show; we always don’t spend the extra money and regret it later, so this time, one last time, we were not going to make that mistake. I said I wanted to hear “Bertha,” and we got it, right away, and right away we knew that every single member of the band was completely on, locked in. Bobby, as my friend observed, was “really cooking.” Jeff Chimenti, Oteil Burbridge, Mickey Hart, also cooking. And Mayer—I have never seen him, perhaps, cook like that, leaning into every moment harder than I have ever seen him lean, and he always leans in hard, given that he is probably among other things one of the greatest living guitarists.

“How can I write about John Mayer’s faces?” I typed in my Notes app on the first night of shows. Unfortunately there is no other way I can describe it but to say that while he is jamming he often more or less appears to be on the verge of having an orgasm for three hours straight, and we are with him the entire time.

The thing is, the experience of a good jam-band show really does have quite a lot in common with sex. “Is jamming like edging?” I asked my friend on the first night, and we both burst out laughing, but, well, there’s a reason one of my friends is persistently yelling “Jeff Chimenti make me come!” after a really good keyboard section. With a Dead & Co. show, you sort of know how it’s going to go right from the beginning, because there is kind of a familiar script. The band is probably going to open with something upbeat (“Let the Good Times Roll” is a regular option) and then they are going to lead you through some others (a few jams, a set break, at least a couple definitive hits, an interlude for “Drums” and “Space,” the grand finale, and the inevitable return for the encore, usually slow and sweet). And all the time you are just waiting, waiting, waiting, for that climactic moment when maybe they will drop into “Morning Dew,” or make the pitch-perfect switch from “China Cat Sunflower” into “I Know You Rider.” And yet it’s still surprising, because you don’t know how they’re doing to get there or when, and maybe you will end up somewhere else entirely, like in an extended riff during “Eyes of the World,” but then you come back into yourself, called back by some familiar, beautiful line that is etched into your heart: “There comes a redeemer …” Jeff Chimenti make me come!

This is Jeff Chimenti.

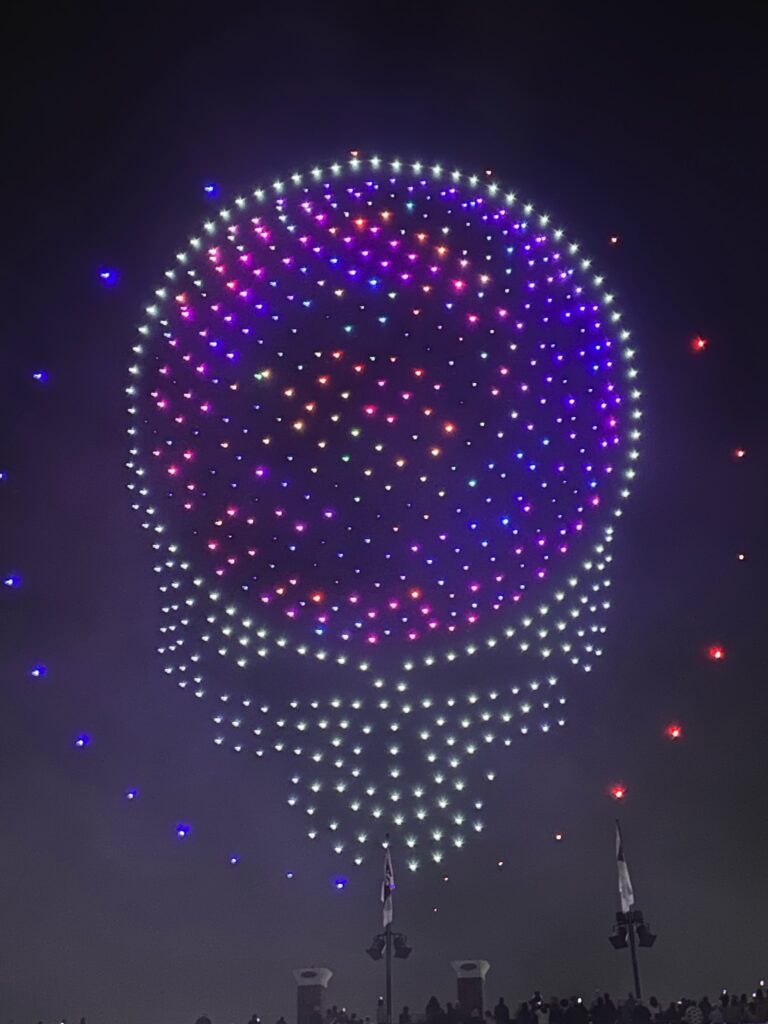

That’s what it’s like for me, anyway; I can’t really say what it would be like for you. But I can say with total certainty that this final night was the best show I’ve ever seen, that everything was superlative. “Good Lovin’,” which is not even that good of a song, was somehow amazing. “Hardest ‘Good Lovin’ ’ ever?” asked a friend. Mayer played and sang “Althea” heartrendingly before a pink sunset. “Best ‘Althea’ ever?” As it got dark, drones flew above the stadium in the formation of the Steal Your Face logo and then later morphed into a skeleton that was tipping its hat to all of us, even to the thousands of people who couldn’t get tickets and were listening from outside the stadium. (Two of my friends were among them.) Thank you San Francisco! Thank you Bobby! Thank you John!

I thought about a poem by Mark Strand, the lines “We began to believe // the night would not end.” And we did begin to believe that, hoping a little desperately for a rumored third set, even though logically we knew there would be a hard stadium curfew, and as someone said last summer, sitting on a curb after the last show of that year, out of cash to buy nitrous, “All good things must come to an end.” But must they? That’s what we’re always wondering and testing, and maybe in part why the ends of these nights can tip toward extremes. The band played the ballad “Brokedown Palace”—“Fare you well, fare you well / I love you more than words can tell”—and then in a moment of surprise, something no one saw coming, one last encore, another version of “Not Fade Away.” They had started the first San Francisco show with that song, and they came back to it, and it was both upbeat and tender, all of us pledging, “You know our love will not fade away!” And the perfect thing is that it won’t.

Steal your face above the stadium.

Sophie Haigney is the web editor of The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/MVB7CpP

Comments

Post a Comment