In an interview in our Fall issue, Robert Glück told Lucy Ives, “I think about the workshops I ran at Small Press Traffic in the seventies and eighties, how reading became a part of writing. We were reading our lives and living our fictions.” We asked Glück—whose free community workshops spearheaded the New Narrative movement in San Francisco—for a syllabus from one of his former classes. This one is from a course called The Displaced Person.

Here is my catalog description: This M.F.A.-level course in fiction explores—through readings, writing assignments, and critical essays—the many ways in which alienation defines the self, from Lacan’s mirror stage, where the self comes to be organized around an image outside of the body, to the various kinds of exile we experience by virtue of class, age, race, and sexuality, as well as the hatred of the other, the discontents of language, and the economies of pleasure that society seems to be founded on.

I assigned class presentations, creative responses based on my prompts, and brief critical responses—two observations supported by examples. Discrete observations allow students to express and get past initial resistance.

My class anthology was more of an environment than a set syllabus. I also taught books—Jane Bowles’s Two Serious Ladies, Philip K. Dick’s Ubik. I had a session on the Gnostics and imported Bruce Boone to talk about them.

Some of the readings:

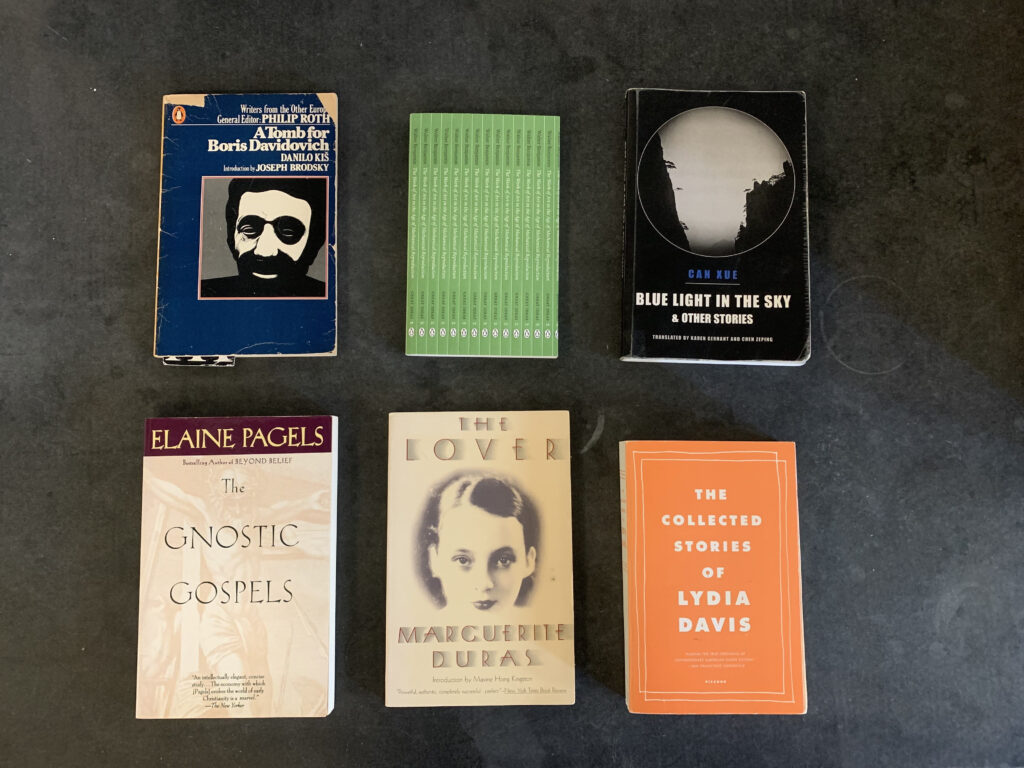

“We Refugees,” Hannah Arendt; “Correspondence with Jacques Rivière,” “All writing is pigshit …,” “Fragments of a Journal in Hell,” and “Van Gogh: The Man Suicided by Society,” Antonin Artaud; stories by Isaac Babel; Back Roads to Far Towns, Basho; Company, Samuel Beckett; “The Collector of Treasures” and other stories by Bessie Head; “Enrique Martín,” “Last Evenings on Earth,” and “Dance Card,” Roberto Bolaño; “The Gloomy Mood of Ah Mei on a Sunny Day,” “Raindrops in the Crevice between the Tiles,” “Soap Bubbles in the Dirty Water,” “The Fog,” and “Hut on the Mountain,” Can Xue; “The Dead Man,” “Madame Edwarda,” and “The Notion of Expenditure”, Georges Bataille; “The Idyll,” “The Madness of the Day,” and “Foucault/Blanchot,” Maurice Blanchot; “Sleep It Off, Lady,” Jean Rhys; “The Mirror Stage,” (this is quite a good cartoon explanation of Lacan’s theory) Jacques Lacan; Diary, Vaslav Nijinsky; excerpts from a day in the life of p., kari edwards; excerpt from Great Expectations, Kathy Acker; The Return of Painting, Leslie Scalapino; “On the Line,” Deleuze & Guattari; from Soft Architecture, Lisa Robertson; from Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva; from Ugly Man, “The Ash Gray Proclamation” Dennis Cooper; poems of Paul Celan; from The Lover, Marguerite Duras; from Wittgenstein’s Nephew, Thomas Bernhard; from The Bruise, Magdalena Zurawski; A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, Danilo Kiš; “Robin,” “1969,” Eileen Myles; “Hashish in Marseilles,” “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” and “The Storyteller,” Walter Benjamin; “We Refugees,” Giorgio Agamben; from The Arab Apocalypse, Etel Adnan; “Splendor in the Wind,” Raúl Zuritas; “Thomas Gospel” and other gospels from the Gnostic Gospels. Other writings included works by Lydia Davis, Fanny Howe, Camille Roy, Darius James, Charles Baudelaire, Edmond Jabès, and Mehdi Charef.

Sample assignment:

Write a page or two of wisdom literature. By that I mean, what you think the truth is, however you want to put it. No parodies of the Bible please.

Robert Glück is the author of nine books of poetry and prose, including the novel Margery Kempe and the long poem I, Boombox.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/JBZfWhL

Comments

Post a Comment