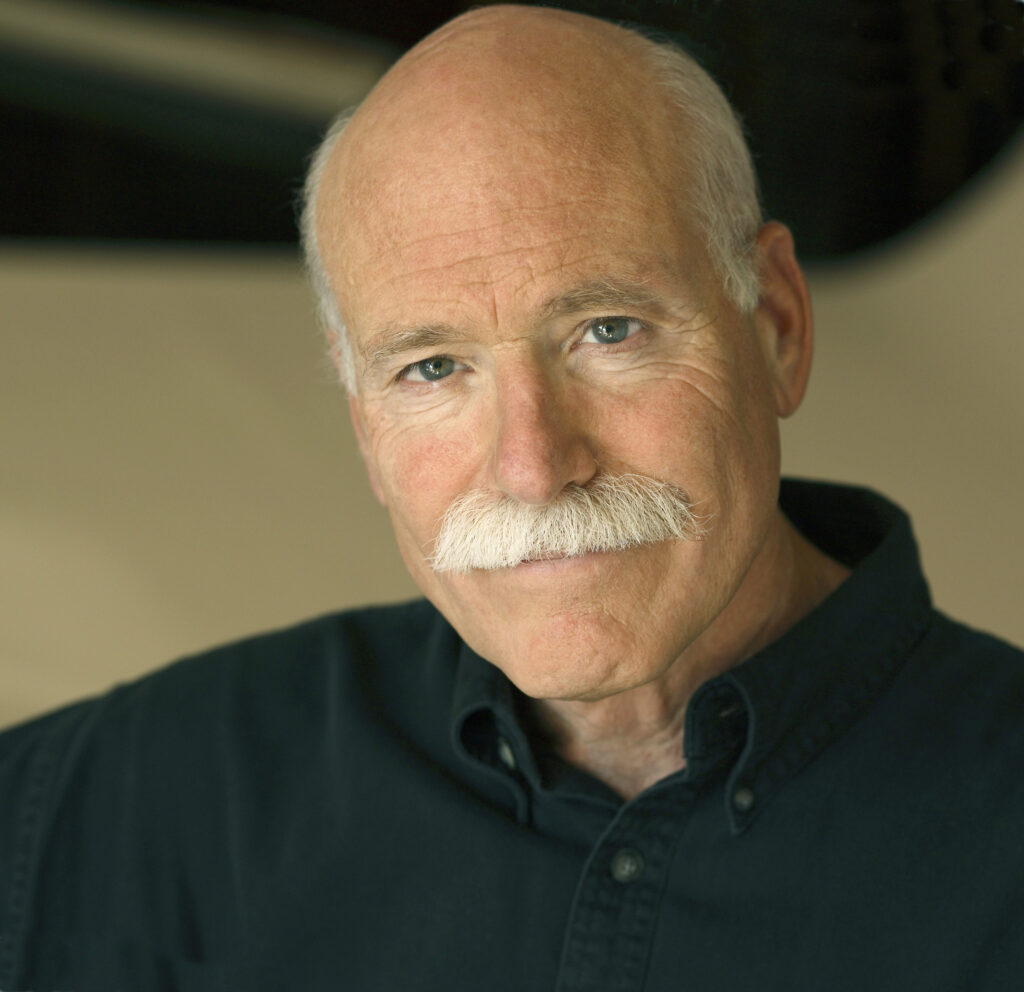

Photograph by Elena Seibert.

In an interview published in The Paris Review no. 171 (Fall 2004), Tobias Wolff pinpointed the radical power of a well-written story. “Good stories slip past our defenses—we all want to know what happens next—and then slow time down, and compel our interest and belief in other lives than our own, so that we feel ourselves in another presence. It’s a kind of awakening, a deliverance, it cracks our shell and opens us up to the truth and singularity of others—to their very being.”

The Paris Review has always sought out just this kind of writing, of which Wolff’s own body of work is an extraordinary example. We are thrilled to honor him with the Hadada, our award for lifetime achievement in literature. Previous recipients include Joan Didion, Philip Roth, Lydia Davis, Jamaica Kincaid, and Vivian Gornick.

Over the last several decades, Wolff has established himself as a virtuosic storyteller across several forms. His memoirs, novels, and short stories express, in infinite variety, the human struggle to reconcile the truth we wish for with the one we get. In This Boy’s Life (1989), his memoir about a peripatetic childhood—which won a Los Angeles Times Book Prize—and Old School (2003), his novel modeled in part on his own disastrous attempt to fit in at an elite prep school, he captures the vulnerability of youth with precision and delicacy. His books set during the Vietnam War—which include a memoir, In Pharaoh’s Army: Memories of the Lost War (1994), and a novella, The Barracks Thief (1984)—bring the candor and intimacy of personal experience to one of the defining events of the last century. In Pharaoh’s Army was a National Book Award finalist, while The Barracks Thief won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction.

Wolff may be best known, however, for his short stories, which have been published in four collections—In the Garden of the North American Martyrs (1981), Back in the World (1985), The Night in Question (1996), and Our Story Begins (2008)—and anthologized widely. Wolff’s stories are defined by their capaciousness and expert construction, from the brilliant title story of his first collection, in which a beleaguered professor fights against the stultifying demands of the academy, to “Nightingale,” a standout from his most recent collection, which depicts the anxious ruminations of a parent who has just left his son at an ominous military academy. Many readers will have first encountered his work through the story “Bullet in the Brain,” originally published in The New Yorker in 1997, a kaleidoscopic account of a jaded critic’s last moments on earth that transforms, unexpectedly, into a reverie for the things in life worth remembering. Widely recognized as a master of the form, Wolff has won three O. Henry Awards, as well as The Story Prize, and has been honored for excellence in the short story with both the PEN/Malamud Award and the Rea Award.

“I remember exactly where I was when I first encountered the staccato prose of Tobias Wolff,” says the Review’s publisher, Mona Simpson:

It was December and I was in a tiny apartment in New York City, without a kitchen. I was reading “An Episode in the Life of Professor Brooke.” It was snowing outside, the flakes fizzing in the air shaft, and I was rushing through the story, gulping it down, as if it contained essential nutrients. I’m almost certain I made a sound—I was alone in the apartment—when the woman lifted off her wig. Though I didn’t think of myself as prudish, I was startled when Professor Brooke stayed the night, almost against his will, and felt a new era in my own life begin. Suffice to say, I ordered nine hardback copies of the collection In the Garden of the North American Martyrs, which contained this story, so that I could give one to everyone I loved. I’d never before spent so much money on books—so for this one reader the story ended one more time, with the discovery of the pleasure in generosity.

Many of us at The Paris Review have a favorite Wolff story that we turn to at specific moments for solace, for a laugh, or for spiritual help. Those of us over forty remember rushing to the newsstand to buy a copy of The Atlantic Monthly after a friend called to say there was a new Tobias Wolff story out. One of us recalls reading all of “The Other Miller” while walking home. It’s a great pleasure now to introduce students to Wolff’s stories—standards in anthologies, firmly entrenched in the canon—that we first read on flimsy paper, standing up. Though we can’t claim to have discovered Tobias Wolff, it’s in the spirit of rediscovery and acknowledgement of rightful place that we award him the Hadada prize. His work, in its vernacular beauty, its depth, and its moral capaciousness, deserves the lasting and glorious reputation we hope to insure.

Currently the Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University, where he was previously a Wallace Stegner Fellow, Wolff also taught for many years in the graduate writing program at Syracuse University. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a recipient of the Whiting Award, and in 2015, President Barack Obama presented him with the National Medal of Arts. We look forward to presenting him with the Hadada at our Spring Revel—an annual gathering of writers, artists, and friends to celebrate the Review and honor writers—on April 2, 2024. Tickets are now available, and all proceeds help sustain the magazine. We hope you’ll join us.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3INxZn2

Comments

Post a Comment