Photograph by Timmy Straw.

In childhood, books have a smell. Not an actual smell: I’m not talking about the sweet mustiness of a Knopf hardcover circa 1977, or the creaking sawdust odor of a Bantam paperback. I mean that, in childhood, books have the hunch of a smell: the way, later in life, you might suspect that each thing has a noumenon, a reality independent of our apprehension of it. In childhood, a given book’s particular smell—though it might actually smell, like snow, of absolutely nothing—emits a kind of hovering mysterious message: here is something you can give yourself up to, it seems to say; here is something you can give yourself over to, and at the same time never quite reach. In this sense, in childhood, books are more serious than they’ll ever be again.

In childhood, you find a book in the library, or you’re handed one—in my case, my reading program circa 1990 was shaped by a saturnine and pinchingly generous librarian named Cynthia, who noted our shared inclination toward what I might now call optimistic gloom and gave me, at the age of eight, a children’s series on environmental disasters: Chernobyl, Bhopal, Three Mile Island, Love Canal. It was Cynthia—alarmingly old, nimble, with fraying hair, and whose face seemed to shatter when she smiled (a wonderful moment in itself, though it was scary to see her face reassemble into its usual austerity, like watching the breaking of a water glass in reverse on VHS)—it was Cynthia who gave me Robert Cormier’s 1977 YA novel I Am the Cheese.

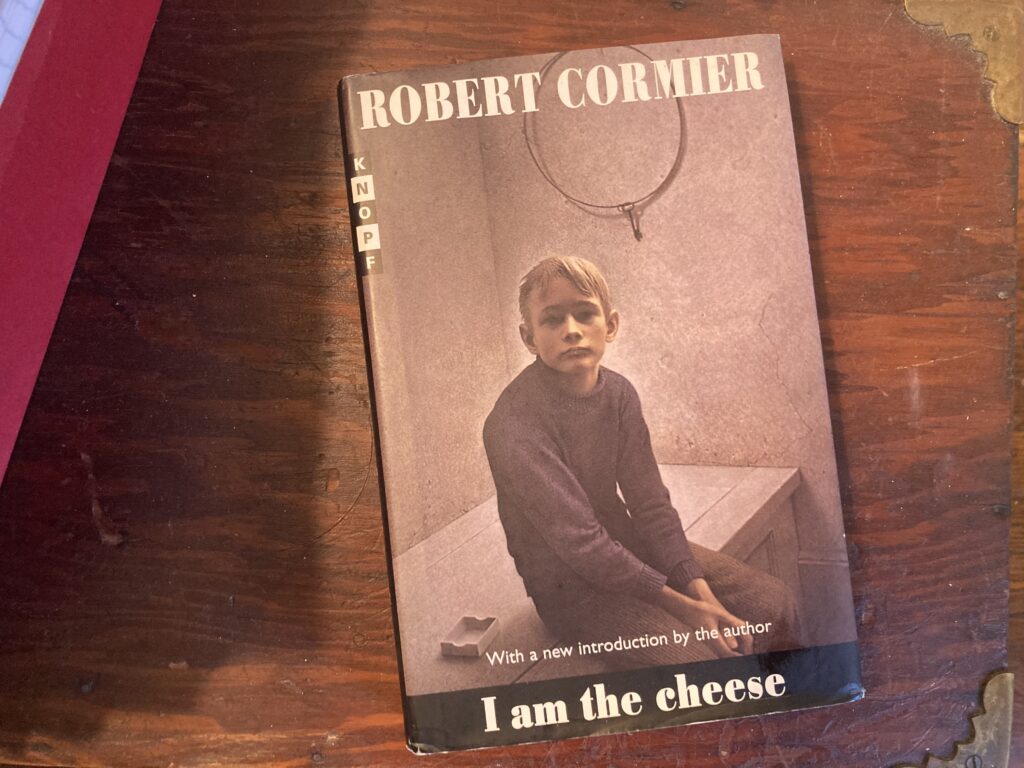

The cover of the book was promising, I saw. It showed a boy, such as I both thought and wished I was, maybe twelve years old, with a wistful, reluctant look, big ears, and sharp elbows; he’s in the gray wash of a prison cell with cracked concrete walls, a wood pallet for a bed, a key (weirdly—why the key?) on a peg behind him. And I had a hunch of the book’s smell, certainly: it was something contiguous to the feeling of an fall morning, and to the horizon looking south, out of town; contiguous, too, to the brackish salt sense of future adulthood, of workdays and money fear, of someone, someday, mysteriously wanting to kiss you. In it I sensed some shadow of the future—as adulthood is, for kids, both inevitable and impossible; as childhood can be intuited, when you’re a kid, as the long shadow of your own adult body cast back onto your child present. I Am the Cheese contained a message for me, I felt. I read the whole thing in one go, one morning in the back of our Datsun Maxima, headed to the mountains, probably, the Oregon Cascades, with the ever-present smell of cut grass and gasoline in the car from my father’s landscaping work; I read the whole thing as though goaded to—whipped on like a dog in a pack of dogs behind the musher of the book.

It’s a paranoid book, and desolate—written, I now understand, at the end of the Vietnam War, around Watergate, the grimmer surfaces of world order newly visible in the first hints of Cold War melt-off—and it was hypnotizing. I dread descriptions of plot, blow-by-blow accounts, but suffice it to say here: I Am the Cheese involves a family swept up in the nascent witness protection program via the father, a small-town-journalist-turned-whistleblower to the violent excesses of government corruption. The book unfolds through the consciousness of the family’s only child, a quiet boy named Adam, and it takes place in the fall, in New England (itself a thrill: me, who had never left Oregon except to visit, once, Fresno). And it is threaded through with references, tightening my ignorant heart to anticipation: references to jazz; to Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel; to petty shoplifting; to the perpetual haunting of the father; to shabby motels, diner hamburgers, pay phones; to conspiracies, details, forms of love and betrayal organizing like ice crystals just behind the surface of things.

It turns out, however, that this anticipation of the heart feels quite different in reverse—rereading the book this month, I was unnerved to discover how many fantasies, desires, impulses that I had thought my own were in fact informed by it. I saw that I had, for instance, unconsciously interpreted a number of difficult and very real events in my own family through its fictions; I saw too that several people with whom I’ve fallen in love share a glimmer of psychic resemblance to the girl Adam loves. I was unnerved to discover, in short, that a YA novel could be the source of a greater portion of my instincts and reflexes than seemed at all appropriate; that it could make desirable—so desirable, in fact, as to seem outside of desire—a whole array of emotional tendencies: toward shame, melancholy, irreverence, estrangement. As in: hi-ho, the dairy-o, the cheese stands alone.

In childhood, you find a book in the library, or you’re handed one; and how you find the book, and when, and precisely where you are when you read it—these things matter enormously. The quality of the light, the mood at home, the facts of material circumstance, so normalized as to be both total and unconscious—in childhood these are as much the experience of the text as is the text in itself. The book and the situation in which you read it form a single weather, and this weather contains you—it enfolds you, as Walter Benjamin writes in the fragment “Child reading,” “as secretly, densely, and unceasingly as snow.” It’s easy to think, then, that there is some aspect of yourself still sitting, mittened and suited up, strangely warm, in that same falling snow; still turning the pages, even now. And to think, too, that this is true no matter how ridiculous, or desolate, or paranoid, or merely competent the book—in the light or dark of your adult present—now appears. Or maybe it’s this: that your hunch of the book’s smell—its noumenon, if I may—is in some strange way bound up in an awareness of your own.

Timmy Straw is a poet, musician, and translator. Their poems “Brezhnev” and “Oracle at Dog” appear in the Review‘s Winter 2022 issue, no. 242.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/jrv4LtY

Comments

Post a Comment