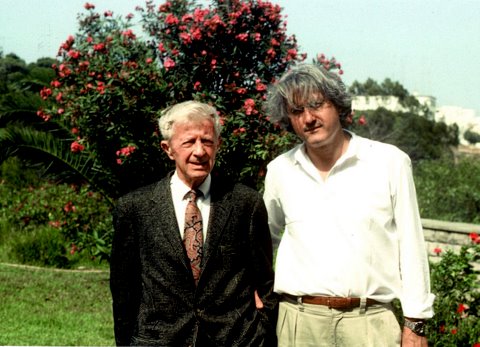

From left, Paul Bowles and Frederic Tuten in Tangiers in the eighties. Photograph courtesy of Frederic Tuten.

I immediately found a taxi in front of my hotel, which I thought meant good luck for the venture ahead. The driver smiled. I smiled. I gave him the directions in Spanish, then French, and finally I gave him a slip of paper with an address. He smiled. We drove slowly up and down hilly streets and then into a valley of people selling carpets and kitchenware; a mosque towered above us. We passed a man walking with a live lamb draped over his shoulders. It was my second day in Morocco, and I was not yet used to such biblical scenes.

Ten minutes later, I saw the same spread of carpets and the same array of pots and pans, the same mosque, and I gestured to say, What’s going on? He shrugged and gave me another of his wide smiles. I was not reassured, thinking of stories of kidnapping and worse that supposedly happened in Morocco, stories I had admired written by a man I had admired since I was sixteen and whom I was on the way to meet. But then, finally, I arrived safe and free, ten minutes late and lighter by thirty dollars—with tip.

Paul Bowles was already there, waiting for me on a bench at the American School’s entranceway. He was very thin, slight, in a beige jacket, gray trousers, and a narrow, quiet tie, and was smoking a cigarette in a holder.

“I hope you had a good ride,” he said.

“Fine. There was a cab waiting at my hotel. The Hotel Villa de France,” I added, with a certain pride, because Matisse and Gertrude Stein had once stayed there. “It took only forty minutes.”

“Oh!” he said. “You could have walked here in less than ten. But then, I suppose, you’d have to had known the way. That’s a good hotel,” he added, “or at least it was forty years ago. Is the place still run-down?”

“A mess, but lovely,” I said. I had loved breakfast there on my first morning—a pot of coffee and a full glass of fresh orange juice and toast wrapped in a linen napkin—on a table set among flower beds and under a jasmine tree. It was a luxury I had never enjoyed before and that I now dreamed of enjoying for the rest of my life.

“Be sure to set aside some water because it shuts down citywide every few days or so, and the electricity, too.”

I thanked him. But I had already been forewarned and that morning filled up my bathtub with cloudy water.

“We have a mutual friend,” I said.

He smiled. “Oh! Yes?”

“Susan Sontag. She told me that she had once visited you here in Tangier. She asked me to give you her warmest regards.”

“She sent me a collection of her stories some while ago.”

“I, etcetera, I think it is,” I said. “It came out a few years ago.”

“Yes, that’s the one. Have you read it?” he asked, with a slight incline of his head.

“Well, not all the stories,” I said.

He smiled. “Why did she bother to write them?”—his voice like a creaking door.

His cutting words about a mutual friend shook me and made me think the less of him, and I went on guard. But I was also pained because Bowles was one of my earliest heroes.

I had admired him since my teens, thirty years earlier, when, in a dark apartment in the Bronx, I had first read his The Sheltering Sky and dreamed of the day when I would travel to exotic places and have adventures packed with danger and meaning. Outside my Bronx window was a road and, beyond that, an elevated subway. Within walking distance was the Bronx Zoo and the botanical gardens, divided by a muddy stream they called a river. Except for excursions into Manhattan, I had not traveled anywhere outside of the Bronx, although one day my cousin took me on a day trip upstate. I was fifteen, and for the first time I saw a cow.

I later made up for my provinciality and had since traveled to South America and Europe and was now living in Paris trying to write my next novel; it had been ten years since I’d published my first: The Adventures of Mao on the Long March. It had had some critical success, and on the strength of it, I had gotten a Guggenheim grant to write my second book, a novel about the Belgian comic strip character Tintin. I had heard from Sontag that supposedly well-meaning friends had little faith that I’d ever finish another novel and they said that I had gone to live in glamorous Paris to cloak my failure.

“I don’t think that,” Susan said. “But you should know.”

I tried to shrug it off, but it stuck with me. I had done other writing in the years following the first novel, starts and stops, one about a fascinating eighteenth-century mountebank, Count Cagliostro, who had an unwitting role in the French Revolution and about whom Alexandre Dumas had written a five-volume series. I must have written a hundred pages before I gave it up and went to a novella about windows.

It took me a long time—but that’s another story—before I understood that my fits and starts in writing had no aesthetic grounds but were the result of my ever-increasing drinking, which had started as drinking to get the writing machinery in gear, and after a while the gears were in full motion but not to write, only to drink.

In the meanwhile I wrote, slowly, my Tintin novel. There was a nagging feeling that whatever else I wrote, it was still not my second novel, and in my generation, only the novel mattered, and the bigger, the better, the more important, the more American. I had never shared that feeling. I wanted the writing to be trim and tight and evocative. In a Paris Review interview, Georges Simenon said he was influenced by Cézanne, who in three strokes, he said, created the essence of an apple, the essence of apple.

***

When sometime in the spring of ’81 I received the letter from the School of Visual Arts, in New York, asking me if I would like to teach a summer writing class with Paul Bowles in Tangier, I knew immediately I wanted to go. His was the kind of tight and evocative novel that I most admired. His was a life set apart from the ordinary, the competitive, the “literary.” Was he not also someone who had left his country?

I had a good reputation at SVA, where I’d moonlighted, teaching a literature class for more than fifteen years called Civilization and Its Discontents. The school thought that I would make a good team with Bowles, who had conducted the class the previous summer with small success.

Writers had landed in Tangier from afar to study with him, mostly young Americans from the States and a few expatriates living in Europe. Some had come for the lure of his writing; some had never read him, but many came for his fame as a proto-Beat character, a friend of Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs and other romantic renegades who had visited him in Tangier decades earlier. Whatever their reason for wanting to work with Bowles, many students were disappointed by Bowles’s formality and personal reserve and, most importantly, his uniform coolness to their work. SVA thought I might enliven the atmosphere and take down the classroom chill.

I had been nervous to meet Bowles because I had admired him for so long. I was nervous, too, because the situation was awkward. I did not know how SVA had proposed to Bowles the idea of my coming and with what tact or how he had reacted, so I was concerned that he would dislike the new situation and, by extension, dislike me, so on the morning of our first meeting I went right to it.

“I hope you don’t mind my sharing the class with you, Mr. Bowles,” I said.

“Not at all,” he replied. “I have no idea what to do. I’ve never taught before, and I’m not even sure that writing can be taught. And please, call me Paul.”

“Neither am I,” I said. This was true, but I also wanted to share a common ground, wanted to please him.

I had brought my copy of The Sheltering Sky for him to sign but felt that it was too soon to ask. An old Mustang came up, and Bowles waved. It had come to take him home, and I understood that our meeting was over. I was flustered, and I blurted out, “I admire you, Mr. Bowles.”

“Admire me? Why would you do that?” he asked, seemingly taken aback.

I wanted to tell him that I carried The Sheltering Sky with me wherever I moved. I wanted him to know how much I admired his life, which he’d invented on his own terms.

“Because I do,” I said, feeling foolish.

In a few days, we settled into a workable routine. We met at 10 a.m. in an airy room at the American School. We sat side by side at a desk on an elevated platform. In the workshop mode, the students commented on and criticized the work under discussion. Then it was my and Bowles’s turn. Paul lit up a cigarette filled with kif and stayed silent while I began to make my remarks.

I tried to find merit in even the most terrible pieces. My point was to encourage what was best in the work and where I thought it could be improved upon. In short, I was little interested in plot, arc of the narrative—all that could come later—but I wanted to find specific entry points that would open the writer to seeing his or her whole story freshly. I also made a point of saying that writers grow at different paces and that the most important thing was to keep writing. No one could ever have imagined that the author of Cup of Gold, one of the worst novels on the planet, was to be the author of such great novels as In Dubious Battle and The Grapes of Wrath.

Bowles was always polite, reserved, but nothing the students wrote pleased him or ever met with his approval—though he never expressed disapproval—thus leaving everyone disappointed. Everyone wanted his approbation, of course. They had come for that, for him, after all. I was just the sous-chef; he the chef. Whatever good I may have found in their work mattered less than his coolness to it.

Bowles saved his few comments to indicate where a semicolon or a paragraph or a tense change was needed: “On page four you say, ‘He thought to buy her flowers.’ But surely you mean, ‘He had thought to buy her flowers.’ Or I imagine you had meant that.”

Once in a while, when a word seemed inexact or inappropriate, he would dwell a bit on the writer’s need to find the mot juste. He never spoke of the story as a whole, never measured the degree of its success, never addressed the writer behind the effort.

He was far away from us all. The kif he smoked throughout the class fueled his distance. But ill at ease in doing what he felt ill-equipped to do, and pinched as he was in class, Bowles welcomed students to his apartment.

“Come for tea,” he’d say to almost anyone who asked to see him.

I was amazed that he was so broad and indiscriminate with his invitations. I should not have been surprised though, having earlier learned from him that over the years young people from all over Europe and the States would just show up at his door.

“What do you do, Paul, then?” I asked, somewhat appalled by the prospect of strangers knocking at my apartment door in New York or anywhere on the earth.

“I let them in, of course. What else can I do?” he asked, with an air of fatality.

You could have tossed them out, I wanted to suggest. But his sense of real or pretend resignation extended to everything. The world revolved as it did and as it would, and he had no part in its turning. People barged in at his door, and he couldn’t refuse them. But the truth was that he was lonely for company. The recent winters in Tangier, he told me, when he’d had few visitors, were especially bad. He could count them on a hand and tell you who they were. “A Swiss couple and then, in March, a Dutch painter.” He was lonely for his native language, as well. It was obvious that he was distant from contemporary American idiom. Sometimes, he stopped to ask a student what a phrase or a word meant in a story because it was foreign to him.

“You say here, ‘it’s the bomb.’ That’s odd.”

Of course, the students were amused, and his lapses gave him a bit of color.

“Why don’t you come back home?” I once asked.

“To live where and to do what? And where would I get kif? And anyway, how could I afford it?” I knew his rent was fifty dollars a month in a well-kept building. It even had a garage for his car.

By his account, he had no money, living on interest and some funds he was vague about—maybe he drew in four or five thousand dollars a year, he said. “Where else could I live on that?”

I had no answer.

“Besides,” he said, “it’s cold in New York.”

“Paul,” I said, “there are hundreds of people in New York who love your work, and I’m sure that there are tons of people to help you live in the city.” I thought of all the beneficence bestowed on writers by patrons, how Peggy Guggenheim sent Djuna Barnes a monthly check for rent, how Nancy Cunard lavishly supported James Joyce. I was sure there’d be rich people to take care of Bowles well into his old age. But I did not say all of this, feeling instinctively that he was not someone who would react well to the idea, being the ward of a patron, however glamorous the bestower. In fact, I realized that this was my fantasy.

***

On my second week in Tangier, Paul asked me to come to tea, and I kept finding excuses to postpone. I was afraid to visit him, thinking that no sooner would I walk through the door than the Moroccan police would burst in and arrest us all. He smoked kif all day long. In class he’d empty out a cigarette, finger in the kif, stick it in a holder, and smoke away, quietly, inhaling like an Austro-Hungarian aristocrat in a B movie.

I had been told that the police were rough with foreigners who used drugs, often entrapping them, especially the young who had come from Europe and America, and then putting them in prison where they were beyond the protection of their embassies. Bowles had never been arrested for smoking kif, but I was certain that were I with him chez lui, I’d be arrested and sent away to the most depraved prison and stay caged there forever. A fear that was, in part, thanks to Bowles himself, who, from the week I arrived in Tangier, fed me stories of dreadful police-doings.

Here’s one he relished: A middle-aged, conservative British couple on holiday motoring in the Maghreb mountains were stopped at a police barricade and their car searched. One of the policemen produced a package of kif, saying he had found it in their trunk. The couple denied ever possessing or knowing of such an item.

“Someone put it there,” the husband insisted, stopping short of an accusation against the two policemen and feeling assured that his word on the matter was sufficient. One of the policemen answered: “We are not happy. Make us happy.”

The couple was slow to get the point, but when they did they were irate—framed and extorted, they were, an outrage—and they told the policemen that they would be reported to the proper authorities. Husband and wife were arrested on the spot and hauled off to jail, where, finally, someone from the British consulate came dutifully to visit them.

It was a local matter; there was nothing really the consulate could do. But somewhere it was hinted that they could have avoided all that trouble at the onset by giving the policemen just a few pounds, but now they would have to get a Moroccan lawyer and go to court. Perhaps that lawyer could find a way to help them, in any event.

The lawyer suggested certain payments, emoluments to soothe the feelings of the arresting officers and to prepare for the goodwill of the presiding judge, and then, of course, there were his own fees. Having felt a bit of awful jail life and sensing that the outcome of the trial might not be based on their honesty and good word, they reluctantly let their lawyer take care of matters as he had suggested, and everyone who was involved, and some who were not, found their pockets heavier. Yet for all the soothing and the paving of kind feelings, the couple received a sentence of two years.

I was shocked. “Why were they sent to prison after they finally paid them off?”

“To teach them a lesson,” Paul said, smiling.

“How can you stay in such a scary place?” I asked.

“Who said I don’t like to be frightened?”

Always in a beige jacket, creamy, perfectly creased brown pants, and a quiet tie, Bowles was trim and neat, a dapper gentleman, soft-spoken, restrained, and by contrast, fond of wild, excessive people. As I later learned from Paul that his wife, Jane, had been. She’d loved drinking and making scenes in Tangier bars, like Parade. Bowles once suggested I go there. I did. It must have once been a glamorous little hole-in-the-wall with its narrow bar and tall zebra-print stools, but now it was a leftover stage set. It depressed me, and I wondered why Paul wanted me to go there. I didn’t tell that to Paul. He seemed pleased that I had made the expedition, as if I had gone to some shrine. “Jane sometimes fell off those stools drunk,” Paul said. “Sometimes I’d have to go and bring her home.” I felt he relished the memory, as one would of an errant child whose antics, however annoying, always amused.

How did he ever write with her around? I wondered. But then I thought, Maybe she fed an emptiness in him, or maybe he wrote to escape her. Then I thought, finally, What do you know about the mystery of couples?

One day it was clear that if I again postponed visiting Bowles, I would never again be invited to tea and that our relationship would sour. Not that he would make me feel that directly—his indirectness was iceberg-scale—and, liking him, I didn’t want any ill feelings between us. I said that I wanted my girlfriend, Dooley, to meet him and that when she arrived in a week we’d set a date, and we’d both come for tea.

At the start of Ramadan, Dooley and I walked six flights up the newly washed Italian marble staircase to Bowles’s doorway. I was still out of breath when he opened the door.

“Why didn’t you take the elevator?” he asked. “Was it not working?”

“Yes,” I said, “but Dooley is frightened of elevators.”

“So was Jane,” he said, regarding my companion kindly. Paul’s longtime friend and protégé of many years, Mohammed Mrabet, was also there greeting us in faulty Spanish and crippled English.

Tired suitcases stacked high in the corridor stood as totems of Bowles’s travels. I fancied his beige living room, which gave off the glow of the desert at dusk. I felt immediately comfortable. Except for the Moroccan-style banquette, it was exactly like my friends’ Greenwich Village digs in the fifties: a living room with scatter rugs frayed at the edges, a low table for tea, a canvas sling chair. Everything orderly and clean but with the dusty patina of yesteryear. I can’t imagine it ever having changed since the day Paul moved in some forty years ago.

I had read about Mrabet and that he and Paul had been close for more than thirty years. Mrabet was a street urchin of fifteen when he met Paul. Illiterate, he was a natural-born storyteller, and Paul had tape-recorded his stories, transcribed and translated them, and aided in their publication. We settled down to drinking mint tea and exchanged pleasantries. Mrabet suddenly said, “Paul is my Papa!”

“Oh, that’s great,” I said.

“I am married. I have three or four children. I’m a no gay.”

“Oh,” Paul said laughing. “He chased Alfred Chester around the apartment threatening to kill him because he called him my sexy cowboy.”

“He was a big stupido,” Mrabet said. “Paul knows many stupidos. But you’re not one. You’ve never come to bother him.”

Paul laughed. “Because he never comes.”

While we were drinking tea, Mrabet opened a green cloth bag and took out a load of kif, and he and Paul set about to separate the seeds. They started to smoke as they worked. Mrabet offered Dooley some hash. She smoked a bit and seemed staggered. “I feel like I’ve gone through a wall,” she said.

“Do you have anything to drink other than tea?” I asked. I was hoping for a big glass of scotch.

“No. No alcohol,” Mrabet said. “Kif,” he said, with a big smile.

“I have an allergy to all drugs,” I said, “all except alcohol.”

Everyone laughed warmly.

It was such a friendly moment. I felt for the first time since meeting Paul a degree of familiarity and comfort. I liked Mrabet. I liked that Dooley seemed so happy to be there. She too had read The Sheltering Sky and felt, as I had, a deep connection to the characters’ rootlessness and interior isolation. But she had promised that she would never mention this to Paul on first meeting.

“I don’t want to gush like all the others,” she said. “Like I’m sure you have.”

But before we were to leave, Mrabet disappeared into a back room and after a few moments emerged, holding out before Dooley a necklace of assorted trinkets on a string. Paul looked at me amused. It was made up of blue and green beads, waxy shells, glass rings, and pieces of bone. It was the kind of necklace a kid of six makes at summer camp.

“This has great power, much baraka to protect you. Also, to make your enemies sick and stop them from making bad magic against you,” Mrabet said.

Dooley managed to ward off Mrabet without his taking too much apparent offense. He slowly raised the object before my eyes: “Well, what about you—will you buy it for your woman?”

I was foolish enough to ask its price. Bowles whispered to me, “Don’t encourage him.” Mrabet wanted somewhere near $280—the friend’s price, because Paul liked me.

“Oh, that was just some trash he found in the street,” Paul said. “He’s always trying to sell people things—just don’t pay attention.”

Mrabet sulked. He walked us to the door and at the last moment lifted the necklace before Dooley’s eyes. “A hundred dollars,” he said.

***

We were invited back to Paul’s a week later. He said he had something special in mind for our visit. Dooley and I had hardly walked in the door when Paul said, “We’ve got to leave soon. Mrabet has been waiting all morning.”

We were hustled into Paul’s waiting Mustang, Mrabet behind the wheel. Mrabet was smiling, happy, humming. We sped out of the town and into hills and countryside. There were roadblocks and car inspections every so often. The police always did that during Ramadan, searching the cars for alcohol, but we went some way without being stopped.

At our first barricade, Paul and Mrabet gave each other looks as we were waved ahead by the police, and I kept thinking about the story of the two English people. Except that now there really would be kif in the car and our arrest perfectly legal. By Moroccan law, everyone found with people carrying drugs were subject to arrest, whether they were in possession of drugs or not. Finally, trying to sound casual, I took the courage to ask whether they were holding.

“Of course not,” Paul said. “Not in the car.”

“Why? Did you want to smoke?” Mrabet asked. He was pleased at the thought of my smoking kif, trying, as he had, to get me to stop drinking alcohol—a disgusting, fattening thing and also forbidden by the Koran. If I were in his care, he would get me in good condition in three months. A little work each day on his farm and I’d be a new man. He brightened at the mention of his farm.

We were still a little way from Mrabet’s farm, Paul said, for that was where we were going and that being the little surprise he had in mind for us. We drove some half hour, slowing down at the next police barricade, where we were waved on before our coming to a full stop. Paul and Mrabet glanced at each other nervously, and I was sure by their nervous glances that they were carrying kif and that we were just lucky not to have been stopped and searched.

“The police are not interested in us,” Paul said. All the same, there was a nervous edge to them both until Paul suggested they make a brief detour before we got to the farm. Mrabet was all for the detour.

We turned off the road to a narrower earthen one and drove five or six more minutes before bringing the car to a halt on a grassy flat. Asking us to wait a moment, they got out and walked some way before stopping at a tree. They pulled at some branches and sped back to the car. I know I wanted to laugh, and Dooley couldn’t help herself and giggled. But I think they were too busy to notice because they now sat filling two empty cigarettes with the kif from a little pouch they had stashed in the tree. They smoked for a relaxed few minutes, chatting and smiling. Soon their earlier nervous edge vanished, and they were happy.

We returned to the main road and then to a dirt lane that took us to a hilly piece of land. Mrabet beamed. At last, we had arrived at his farm. There was no cultivation, no house, no building of any kind that I could see; no animals domestic or wild, just a field the size of six weedy tennis courts that ended at a ravine. Of course, there was nothing much yet, Mrabet explained, but this was just the start, and he’d expand the property as soon as he had the money to buy the land adjoining his, which—and for who knows how long?—was still available.

Paul gave me a stern look, which at the time meant nothing that I understood. Following Mrabet, we all walked toward the ravine, where at the edge rose something like a mound of sticks and branches. A lean-to, actually, so poorly constructed that I could see a large man sitting, half asleep in it. Or perhaps he was stoned on kif or meditating on the sole cloud floating high above the wide spaces in the roof. He crawled out after Mrabet helloed, standing very tall, elegant in his long, yellow djellaba, being at least four inches above my six-two, and he made several dignified bows to the group.

He was the guardian of the farm, Paul explained, whose duties apart from minding the land and the shed was to shepherd a goat, who was now wandering below us in the ravine. Mrabet was upset with the man and took him aside to berate him for the vagrant goat and for who knows what else. For being asleep on the job, Paul suggested. But the two soon seemed to patch things up, and the man went down into the ravine to retrieve the goat.

“He’s a big stupido,” Mrabet said.

“It would be a good idea,” Paul suggested, “to pay the man occasionally. Maybe then he would sleep less on the job.” Mrabet was paying the guardian fourteen dollars a month to manage the estate, and Mrabet owed him back wages, Paul said. Of course he would pay him, Mrabet said—but the man was already living on the land for free, and “with these people,” he said, in a lowered voice, “you should not give them too much of everything at once.” He took me by the arm and led me away to a stunted tree at the ravine’s crumbling edge.

“Over there,” he said, waving to the land beyond the ravine, “is free land, cheap, only four thousand dollars.”

“Are you going to buy it, Mrabet?” I asked.

“Of course,” he said, extending his arm to the terrain beyond, “then I have all this for my farm.”

The problem was the money. That he did not have the money was the problem. But Paul did. Would I ask Paul for him, explain to Paul how valuable the land would be when it was cultivated and had many goats. Unless, of course, I myself would lend him the money, which he’d pay back in a few years as soon as the farm showed profits. I apologized for not having the money. I did not have it, actually, not even two thousand or a thousand or five hundred. But I would have loaned it to him, expecting never to get it back, for the clear joy his prospective domain gave him, the selfhood of his estate. I was so happy for him, in fact, that a few minutes later, I took Paul aside and asked him to lend or just give Mrabet the money outright.

“Why not, Paul? Think of how happy it would make him.”

“He doesn’t understand these things,” Paul said. “He doesn’t understand the idea of principal and income.”

I didn’t press Paul. Bertolucci’s film of The Sheltering Sky was yet to be made, and although Bowles’s short stories were reprinted, he had not, he told me, yet received any money from the publisher, neither royalty nor advance.

***

The following spring I wrote Bowles from Paris, asking what I could bring him when I returned to Tangier. “Kellogg’s Corn Flakes,” he wrote back on a postcard.

I remembered his telling me how hard it was to get the American Kellogg’s cornflakes, that those he bought at the tiny European market in Tangier were made in Germany and tasted nowhere near the ones he loved. I went to Fauchon near the Madeleine and bought two large boxes, flown in from the U.S., and carried them with me to Tangier that June, the second summer of our teaching together.

Perhaps because he was so pleased, later that month, after our teaching chores were done, Paul brought me to hear a trance musician play his deep reedy flute at the home of Paul’s old friends, a dying Frenchman and his wife.

Paul’s driver on call was a Moroccan with extremely long legs, whose djellaba rose above his ankles. We drove to Old Mountain, where in the colonial days the rich Europeans in their villas partied nonstop. We parked on an earthen side road and walked toward the house. Paul stopped to point out a small cottage that he had once rented. It stood on a cliff’s edge facing the Mediterranean, so that from his window, sky and sea merged into one vast blue slab. “That’s the cottage where I wrote Up Above the World,” he said.

“Oh. Because the cottage is so high up on the mountain here?”

“No,” he said smiling. “Twinkle, twinkle, little star. How I wonder what you are. Up above the world so high,” he said. I had seen him smoke kif but had never seen him high, perhaps because that was his natural condition, to stay quietly high and up above the world.

We walked farther until we were met by our host, a woman in her late fifties, who drew us into a circle of six seated on a knoll a few yards from the house. She was grief-stricken and could hardly speak. She asked Paul in English, “How does anyone ever get over this loss? How did you, with Jane?” Paul did not answer right away. He took her arm and finally said, “We survive.”

Her dying husband lay in a wide stone-and-glass tower about twelve feet high at the cliff’s edge facing the Mediterranean. His wife slid open a window to let the music in, to soothe him, along with the morphine, in his dying. Sitting cross-legged on the grass, the musician played away on his thick wooden flute. Very odd how after a while everything but the music started to melt away. Me, too, melting, until I was only an atmosphere without body, and only a weaving low woody sound was left of the world.

I don’t know how long it was until Paul took me by the arm and led me away from hearing range. He had seen my eyelids fluttering, opening, closing, and he said he knew that I was on the way to a place deeper than normal sleep, to some terrible place, from which maybe I would never return. Perhaps he should have left me to go there to find what that meant. He walked me back to his waiting car, and we drove away. We were silent for a long while. Then, as we came close to my hotel, he said, wistfully, “I would like to have five more years, even three.”

“Of course, Paul,” I said. “You’ll live forever.”

Frederic Tuten has published five novels, among them Tintin in the New World. His memoir, My Young Life, and two recent books of short stories, The Bar at Twilight and On a Terrace in Tangier, are swimming in the world. He is also the coauthor of the cult film Possession.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/5UilT6h

Comments

Post a Comment