Unpublished postcard sent by Elizabeth Bishop, from Special Collections Library, Vassar College. Copyright © 2023 by The Alice H. Methfessel Trust. Printed by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux on behalf of the Elizabeth Bishop Estate. All Rights Reserved.

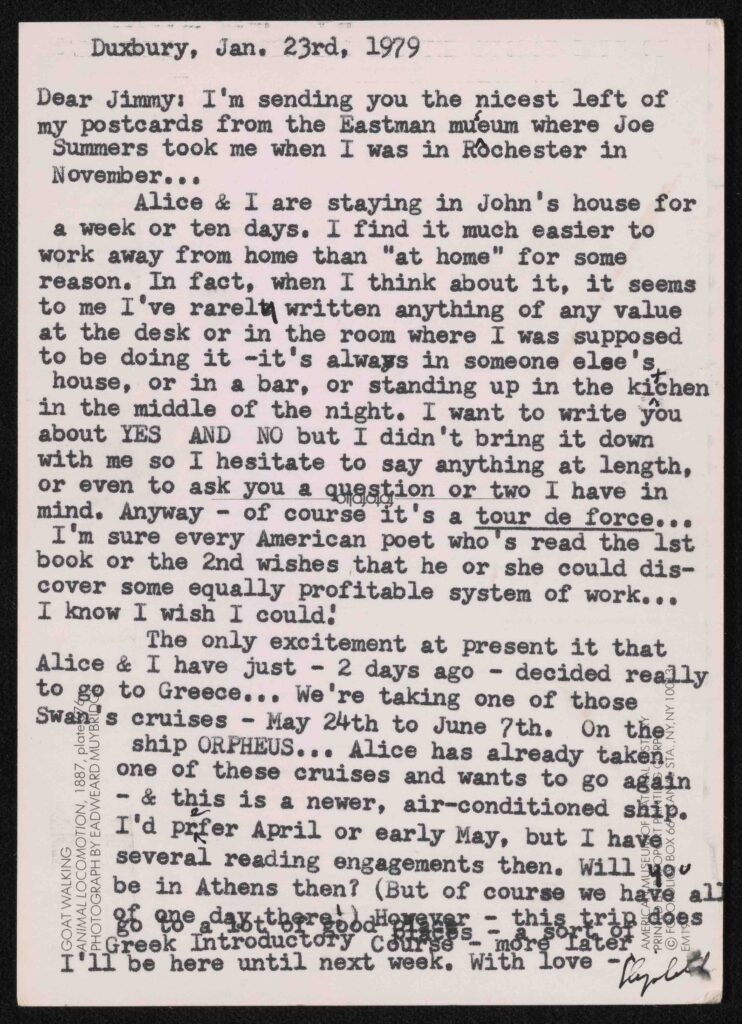

Elizabeth Bishop delighted in the postcard. It suited her poetic subject matter and her way of life—this poet of travel who was more often on the move than at home, “wherever that may be,” as she put it in her poem “Questions of Travel.” She told James Merrill in a postcard written in 1979 that she seldom wrote “anything of any value at the desk or in the room where I was supposed to be doing it—it’s always in someone else’s house, or in a bar, or standing up in the kitchen in the middle of the night.”

Since her death in 1979 and the publication of her selected correspondence, Bishop has become known as one of the great modern-day letter-writers. And yet inevitably something is lost when an editor transcribes a letter to prepare it for print: the quality of the correspondent’s hand (or the model of her typewriter), the paper used, cross-outs and typos, and everything else that fixes the letter in time and space. When it comes to a postcard, or a letter composed on a series of postcards (something Bishop enjoyed doing), we get none of the images, and even more is lost.

But what exactly? “What do we miss by not seeing these postcards?” Jonathan Ellis and Susan Rosenbaum write in the catalogue for the exhibition of Bishop’s postcards they have curated at the Vassar College Library, on view through December 15, 2023. Vassar, which is home to Bishop’s papers, has published print and online catalogues of the exhibition. The print catalogue includes the curators’ richly suggestive introduction, front and back images of the exhibition’s sixty-three items, and appendices.

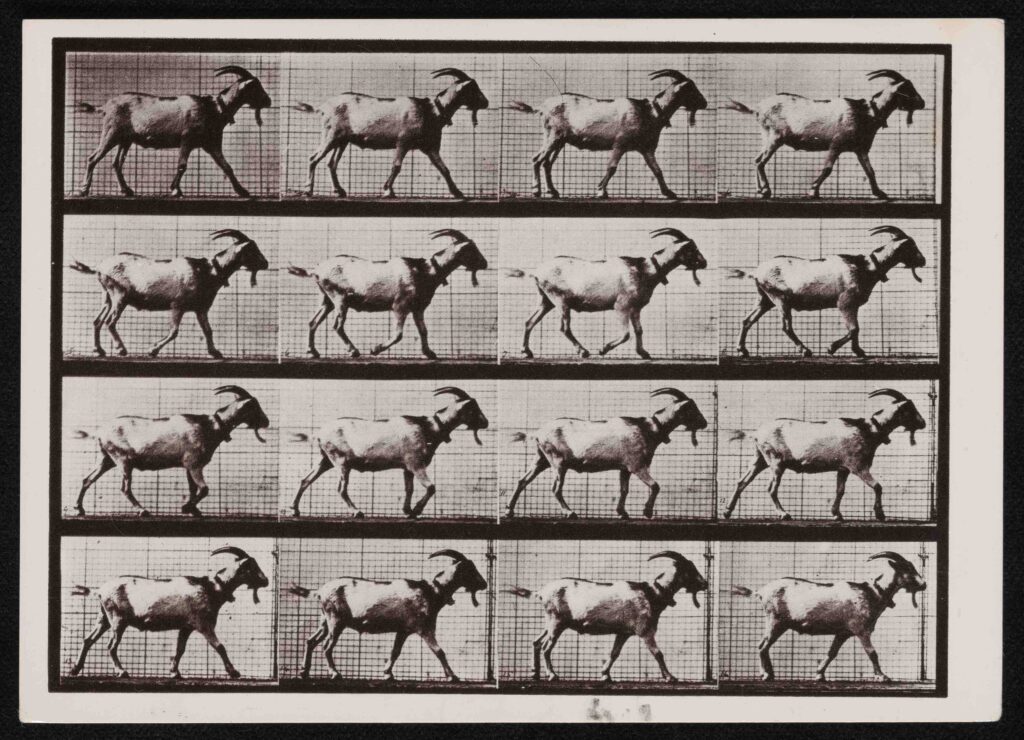

The answer to the curators’ question is: quite a lot. There is always some dialogue between the front and back of one of Bishop’s postcards. Take the one to Merrill commenting on her restless habits of composition. The front of the card (“the nicest left of my postcards from the Eastman Museum,” she says) is a reproduction of the nineteenth-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s motion study of a goat. Bishop doesn’t point out the analogy between her unsettled ways and the ambling goat. She knows Merrill will get it.

Unpublished postcard written by Elizabeth Bishop from Special Collections Library, Vassar College. Copyright © 2023 by The Alice H. Methfessel Trust. Printed by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux on behalf of the Elizabeth Bishop Estate. All Rights Reserved.

But more often, the dialogue between the front and back of the card is explicit, and it plays with the difference between Bishop’s reality and what the postcard pictures. In the middle of one summer, Bishop sent the painter Loren MacIver an image of a stag in an icy stream, thinking “it might make you feel cool … to look at it.” Another postcard to MacIver features a photo of the University Inn in Seattle. The hotel is her “home away from home—temporarily, at least,” while she is teaching for a term at the University of Washington. Lest MacIver get the wrong impression of her circumstances, Bishop corrects the sunny image by drawing a line on the photo and noting that snow is currently falling into the swimming pool.

Postcards began circulating in the late nineteenth century, at first in Europe. These cards carried the address on the front; on the back would be an etching of Salzburg, say, or the Tower of London, and space for a short, handwritten message. A simple but consequential redesign was introduced around 1900: the address was moved to the back of the card, the image to the front. With new visual technologies revolutionizing print media, postal rates falling, and the frequency of mail delivery rising (up to twelve times a day in Paris!), the craze for the postcard took hold. Like other consumer crazes, it seemed to many commentators to be a feminine delirium.

Bishop’s own interest in the postcard began early in her life. In “In the Village,” a short story about her childhood in rural Nova Scotia during the First World War, she describes her mother’s collection of postcards. (Gertrude Bishop must have been one of those women caught up in the postcard craze). The child in the story is thrilled—“how beautiful!”—by her mother’s glitter postcards. “The crystals outline the buildings on the cards in a way buildings never are outlined but should be,” Bishop writes. Compared to those sparkling pictures of distant cities, “the gray postcards for sale in the village store” were a disappointment. “After all,” Bishop reasons, speaking from the little girl’s perspective, “one steps outside and immediately sees the same thing: the village, where we live, full size, and in color.” Notice how young Elizabeth’s sense of reality has been subtly undermined by a taste for postcards. Now reality looks like a representation—a superior one “full size, and in color,” but a representation all the same.

Unpublished postcard sent by Elizabeth Bishop, from Special Collections Library, Vassar College. Copyright © 2023 by The Alice H. Methfessel Trust. Printed by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux on behalf of the Elizabeth Bishop Estate. All Rights Reserved.

Bishop sometimes made greeting cards of her own with crayons and (in tribute to her early enthusiasm for it) glitter. She made her own collages, using, for example, a cigar-box label to create a Christmas card. Ellis and Rosenbaum compare her camp creativity to the collage art of John Ashbery, Joe Brainard, Ray Johnson, and Joseph Cornell. The rectangular frame of the postcard was for her a container something like one of Cornell’s horizontal box constructions. Underlining that association, the Vassar exhibition includes a postcard of one of Cornell’s works that Bishop sent to MacIver in 1977. In “Objects & Apparitions,” Bishop’s translation of a poem by Octavio Paz celebrating Cornell’s work, Cornell’s boxes are called “cages for infinity.”

Postcards are, in their way, a species of propaganda. Whether they show grand public buildings, statues of military heroes, or clichés like a pot of Boston baked beans, they help to constitute a quasi-official discourse, a common image-repertoire that defines what we are supposed to find admirable, interesting, amusing, and so on. Bishop did not disdain popular images of this kind; she enjoyed them, even as she mocked them. That combination of participation and parody is expressed in a souvenir photo postcard that Bishop and her girlfriend Louise Crane posed for at a carnival in France in the early days of their romance. The young women’s faces, poking through a painted sheet, are joined to the burly bodies of two boxers taking swings at each other. While Crane stares coolly at the camera, Bishop makes eyes at her.

Unpublished postcard sent by Elizabeth Bishop, from Special Collections Library, Vassar College. Copyright © 2023 by The Alice H. Methfessel Trust. Printed by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux on behalf of the Elizabeth Bishop Estate. All Rights Reserved.

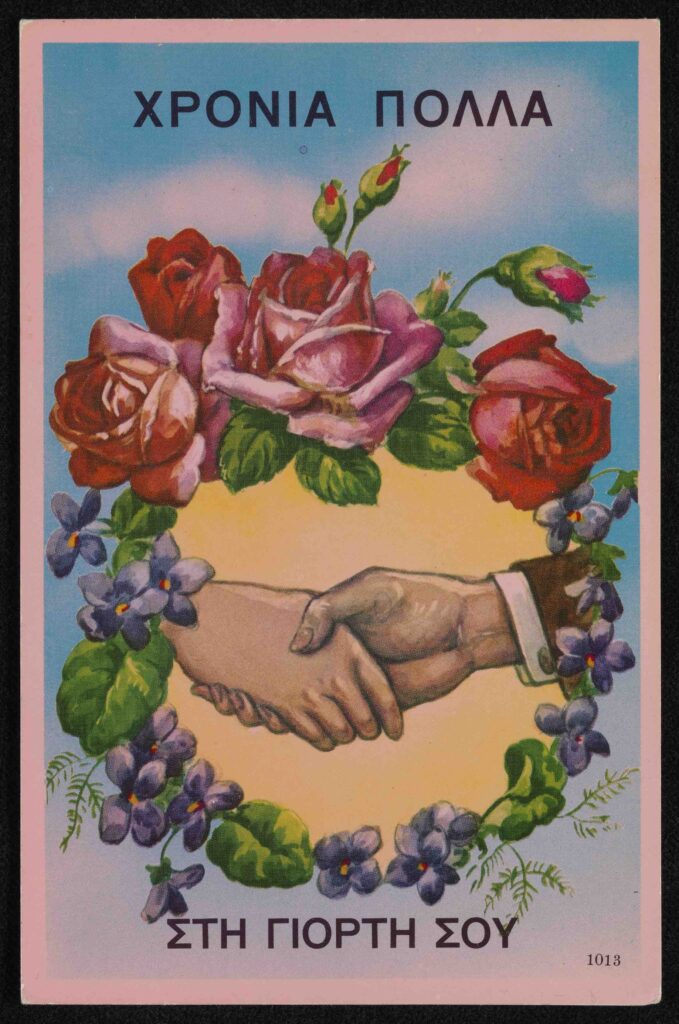

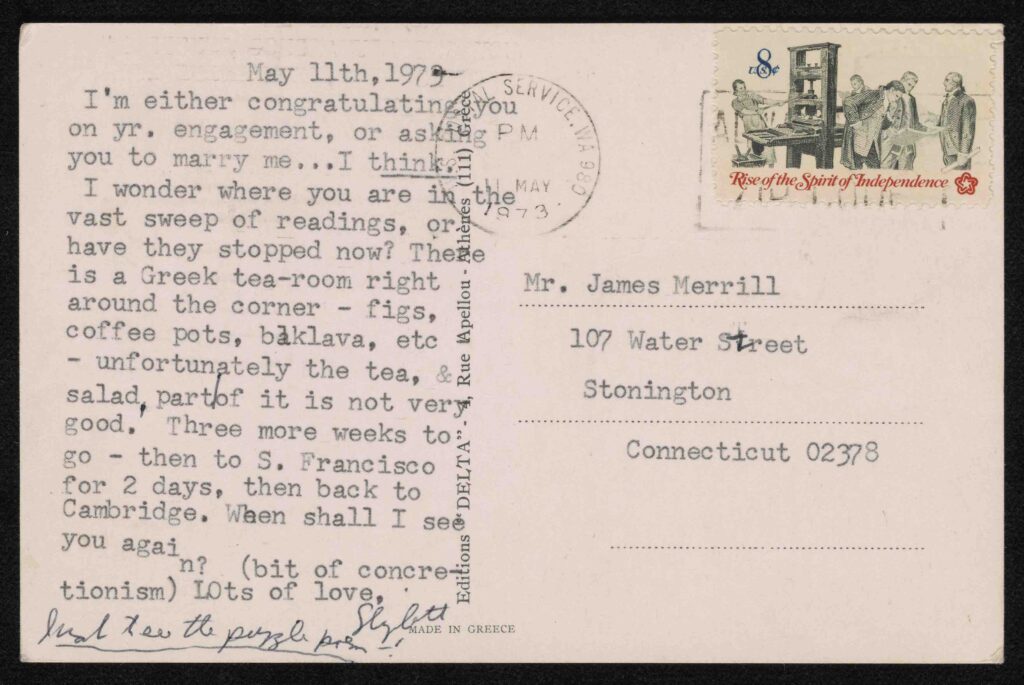

Numerous postcards in the exhibition play with gender norms and suggest queer subtexts. Bishop once sent Merrill a card that wished him, in Greek, “Many Happy Returns on Your Name Day.” Like many of the cards she collected, she must have found this one in a junk shop or used bookstore (0r the Greek tea room she mentions on the card?) and picked it out thinking of Merrill, who spoke Greek and had had, she knew, more than one love affair with a Greek man. The sentimental card pictures a man’s cuff-linked hand shaking a pale, ambiguously gendered hand within a decorative ring of violets and roses. “I’m either congratulating you on yr. engagement,” Bishop types on the back, “or asking you to marry me … I think.”

The cigar-box label that Bishop scissored and sent as a Christmas card to the Brazilian journalist Rosinha Leão pictures a gartered and bewigged eighteenth-century courtier labeled with the words “Our Aristocratic Friend.” This is most likely an affectionate reference to Lota de Macedo Soares, Bishop’s upper-class Brazilian lover, who had introduced Bishop to Leão. Another postcard in the exhibition, this one addressed to Lota, is a reproduction of a Victorian painting by James Collinson of a showily dressed young woman—Ellis and Rosenbaum identify her as a prostitute—who turns to the viewer with a wily smile while holding an empty woman’s purse. Bishop wrote nothing at all on the card but twice underlined the title The Empty Purse. What exactly was she saying? It seems to have something to do with money and sex.

Unpublished postcard written by Elizabeth Bishop from Special Collections Library, Vassar College. Copyright © 2023 by The Alice H. Methfessel Trust. Printed by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux on behalf of the Elizabeth Bishop Estate. All Rights Reserved.

The postcard is an object as much as a message, and sending one, for Bishop, was like giving a gift—it was an expression of attention and care in the form of a four-by-six-inch keepsake. Unlike a letter, which typically suggests a chain of communication, most postcards don’t call for a response. In this sense, the postcard has a one-off, standalone quality not unlike a poem’s.

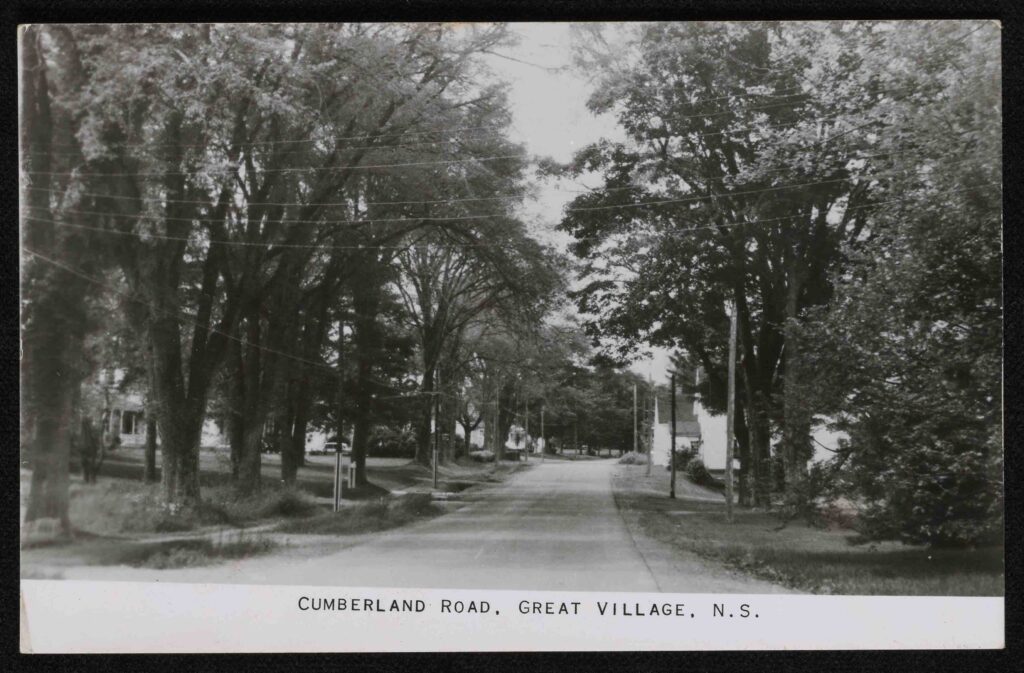

And if Bishop’s postcards are sometimes like poems, are some of her poems like postcards? The first postcard in the exhibition is a photograph from the 1910s, of Cumberland Road in Great Village, Bishop’s grandparents’ home in Nova Scotia. Elm-tree branches arch in a canopy above the road like guards of honor. Bishop never sent the card to anyone. Or we might say, because she kept it among her papers, that she sent it only to herself. She inscribed on the back, as if it were somehow helpful simply to say aloud—for herself? for posterity?—what she knew very well: “I drove the cow to pasture up this road.”

Compare that postcard to “Poem,” from Geography III, the last collection of poetry she published. The subject of “Poem” is a landscape painting of Bishop’s grandparents’ village in Nova Scotia by George Hutchinson, her great-great-uncle. “About the size of an old-style dollar bill,” the oil painting is small and rectangular. We might think of the painting as the front of a postcard and Bishop’s poem, describing and meditating on it, as the message on the back.

Unpublished postcard written by Elizabeth Bishop from Special Collections Library, Vassar College. Copyright 2023 by The Alice H. Methfessel Trust. Printed by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux on behalf of the Elizabeth Bishop Estate. All Rights Reserved.

The poem goes into considerable detail to describe the painting’s representation of Great Village, which was the scene of some of Bishop’s earliest and most powerful memories. In order to get at the reality she recalled, Bishop had to do her best to render the painting’s version of it. This means heightening our awareness of the artist’s medium. Thus the wild iris is “fresh-squiggled from the tube” (as if a first squirt of oil paint were the same thing as a flower blooming), and the “tiny cows” are “two brushstrokes each, but confidently cows.” “A specklike bird is flying to the left,” Bishop notes. “Or is it a flyspeck looking like a bird?” “This attention to the painting’s materiality emphasizes the artificiality of the image, its status as a representation. Rather than make the reality of the scene more remote, it awakens Bishop’s memories and brings her closer to her own experience of the place.

How does that work? And what does it have to do with postcards? The poem and the painting both are pieces of correspondence. What matters for Bishop is an exchange between people: the way the painting triangulates her and her great-great-uncle’s relationship to a “loved” place, preserved by a manifestly artificial and not particularly valuable image. “Our visions coincided,” she says. Then she corrects herself: “ ‘visions’ is / too serious a word—our looks, two looks.” The art of the postcard, for Bishop, was an art of “looks”—shared glimpses and jokes passed from hand to hand, time-stamped, and postmarked.

Langdon Hammer is the Niel Gray Jr. Professor of English at Yale and the author of James Merrill: Life and Art.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/hDnZmgY

Comments

Post a Comment