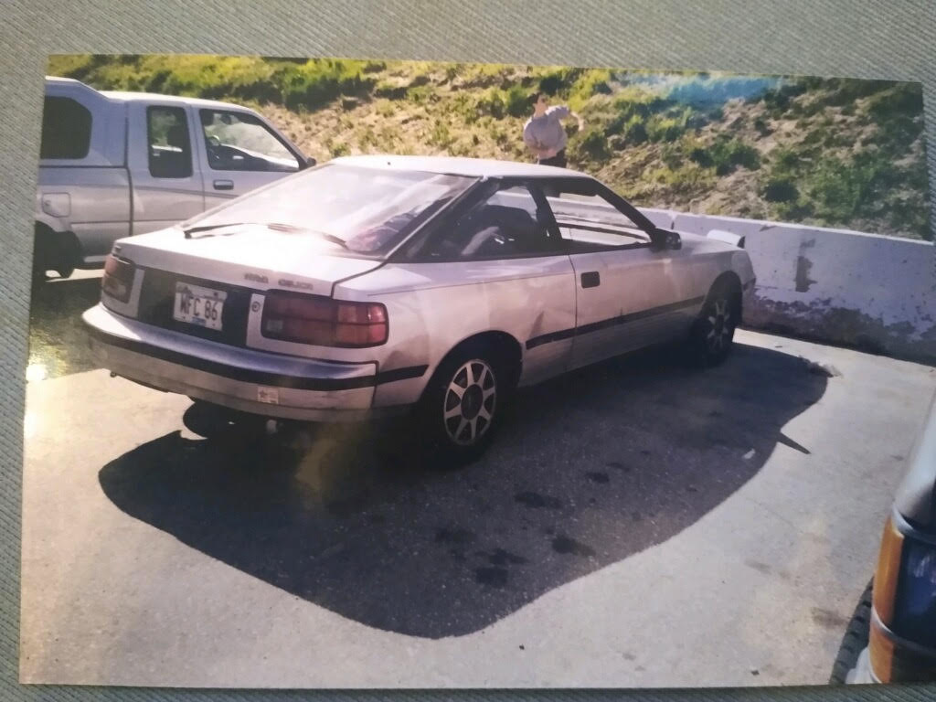

Photograph by Stefan Marolachakis, courtesy of Sam Axelrod.

I turned nineteen and moved to Chicago. Three weeks later, Dave and I bought a silver Celica for five hundred bucks, which, even in 1999, didn’t seem like much for an entire car. Dave named her Angie (short for Angelica, inspired by the elica on the grille, the C having gone missing sometime in the previous eleven years). He was a sophomore at the University of Chicago, and I was his deadbeat friend who had moved to Hyde Park to get out of my parents’ apartment and go be a dropout eight hundred miles away. We liked to think Angie resembled a low-rent DeLorean. The headlights opened and closed—creaking up and down like animatronic eyes—but shortly after the big purchase they got stuck in the up position.

When we test-drove the car around Ravenswood, the steering wheel felt disconcertingly heavy. Oh, that’s just a minor power-steering leak, said the seller. Easy fix. We didn’t know what power steering was, or that the leak was actually expensive to fix, and that we’d have to refill the fluid on a weekly basis. Plus, the hood stand had broken, or disappeared, or anyway no longer existed, so it was necessary to hold up the hood with one hand and refill the cylinder with the other, which was quite difficult to do. Thankfully, there were two of us. We’d been friends since third grade, and with our easy dynamic, splitting a car didn’t seem odd—only convenient.

Growing up in Manhattan, we weren’t allowed to practice driving within the city limits, and most of my friends failed the test once or twice. I’d gotten my license a few days before moving to the Midwest (third try), and was thrilled to be a license-holding car owner. I’d go out at night—sometimes with Dave, sometimes alone—and drive around the neighborhood. Do laps up and down the Midway, blasting Born to Run or Hüsker Dü. That year was probably the freest I’ve ever felt, though I’m not sure I appreciated the freedom. Or maybe it was dampened by loneliness, and feeling like I had little to do with my time. I’d saved up from being the errand boy at a rock club the previous couple years and decided to be work-free in Chicago for as long as possible, with vague ambitions of starting a band. But I didn’t meet many potential bandmates, and my guitar grew dusty. That fall, I’d stay up till five, six in the morning, and sleep till three. Our lives were small. On Sunday nights, Dave and I would go to our favorite Italian restaurant, where we had a crush on the waitress, and then see a movie. Once a month, we’d hand-deliver our insurance payment to Bill, our friendly rep at the InsureOne office in a strip mall on Fifty-Third Street. The Obamas supposedly lived down the street.

When the money ran out, I answered an ad on a bulletin board in the U of C student center. Far East Kitchen was now my employer. Three or four nights a week, Angie and I would deliver juicy Chinese food across the neighborhood: from Forty-Seventh Street to Sixty-First, Cottage Grove to the lake. No matter how I arranged them, the bags of food would often topple over on the floor of the back seat and ooze “gravy” into the carpeting. I got paid by the delivery—on a slow night, I could finish a shift with sixteen bucks in my pocket. Despite the frequent disrespect and lowly social status, I found it satisfying to race around the neighborhood, making my drops. Less so during ice storms. (When, twenty years later and low on funds, I had a brief stint as a DoorDasher in Eugene, Oregon, the satisfaction, unsurprisingly, flagged. By then, Dave was living in a midsize Canadian city with a wife and child. Our dynamic had gone through some uneasy times.)

I was on duty from four to midnight, and spent most of those hours in my office, a.k.a. the car. It’s hard to imagine what I did in there for the longer stretches, especially without a phone. I smoked at the time, and would often extinguish the cigarettes directly into the velour paneling of the driver’s-side door. I did this with as much angst as possible, while listening to Modest Mouse, Cap’n Jazz––the more moody, premillennium boy rock, the better. The car had only a tape deck, and it liked to eat tapes.

Sometimes I’d be parked in my office for a couple hours straight, waiting for the boss, Mrs. Moy, to jut her head into the alley behind the restaurant and beckon me with a finger. I’d walk through the kitchen to get my deliverables, traversing an olfactory obstacle course. When it was too cold to sit in the car, I’d read in a nook in the alcove outside the kitchen. I read The Jungle. I stopped eating meat. Mrs. Moy looked at me funny when I ordered the same free meal every night: noodles and vegetables. No meat, she said. No meat, I said.

I remember leaving my DJ shift at the campus radio station at 4 A.M. one night, driving on several inches of fresh snow, sliding through the spooky South Side streets, listening to Slint’s Spiderland, feeling like the only person alive. I remember gas rising above two dollars a gallon for the first time in history, and worrying this was going to seriously hurt my profit margins. I remember, at the end of the academic year, moving my stuff back to New York, and then, with two other friends, driving Angie to Los Angeles. A low moment: creeping up I-70 at the foot of the Rockies, flooring it but going only twenty-five, cars blowing by us on both sides as the engine started smoking. I remember falling out of the car, 6 A.M., the morning we got to LA, in the most pain of my life. Kidney stone. I remember falling in love for what I thought was the second time, failing to donate sperm, being a sitcom extra, and driving back to New York less than two months later, worrying every few minutes that Angie wouldn’t survive another cross-country trip. She did, but the end was near. In October, a year after she appeared in our lives, with a hint of gravy still in the floor mats, I dropped her at a salvage lot in Hell’s Kitchen. They said she was worth fifty bucks. I made sure to get Dave his half.

Sam Axelrod is at work on a novel, Brief Drama. He lives in Upstate New York.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/ypDRIPs

Comments

Post a Comment