A poet recently sent me an essay by George Oppen called “The Mind’s Own Place,” published in 1963. In it, Oppen grapples with lines from Brecht’s “To Those Born Later”: “What kind of times are these, when / To talk about trees is almost a crime / Because it implies silence about so many horrors?” Oppen, a poet who had withdrawn from writing for nearly twenty-five years to pursue his political commitments, sees Brecht’s concern as valid: “There are situations which cannot honorably be met by art, and surely no one need fiddle precisely at the moment that the house next door is burning.” But he also acknowledges that there is “no crisis in which political poets and orators may not speak of trees, though it is more common for them, in this symbolic usage, to speak of ‘flowers,’ ” which tend to “stand for simple and undefined human happiness.” He goes on:

Suffering can be recognized; to argue its definition is an evasion, a contemptible thing. But the good life, the thing wanted for itself, the aesthetic, will be defined outside of anybody’s politics, or defined wrongly. William Stafford ends a poem titled “Vocation” (he is speaking of the poet’s vocation) with the line: “Your job is to find what the world is trying to be.” And though it may be presumptuous in a man elected to nothing at all, the poet does undertake just about that, certainly nothing less, and the younger poets’ judgment of society is, in the words of Robert Duncan, “I mean, of course, that happiness itself is a forest in which we are bewildered, turn wild, or dwell like Robin Hood, outlawed and at home.”

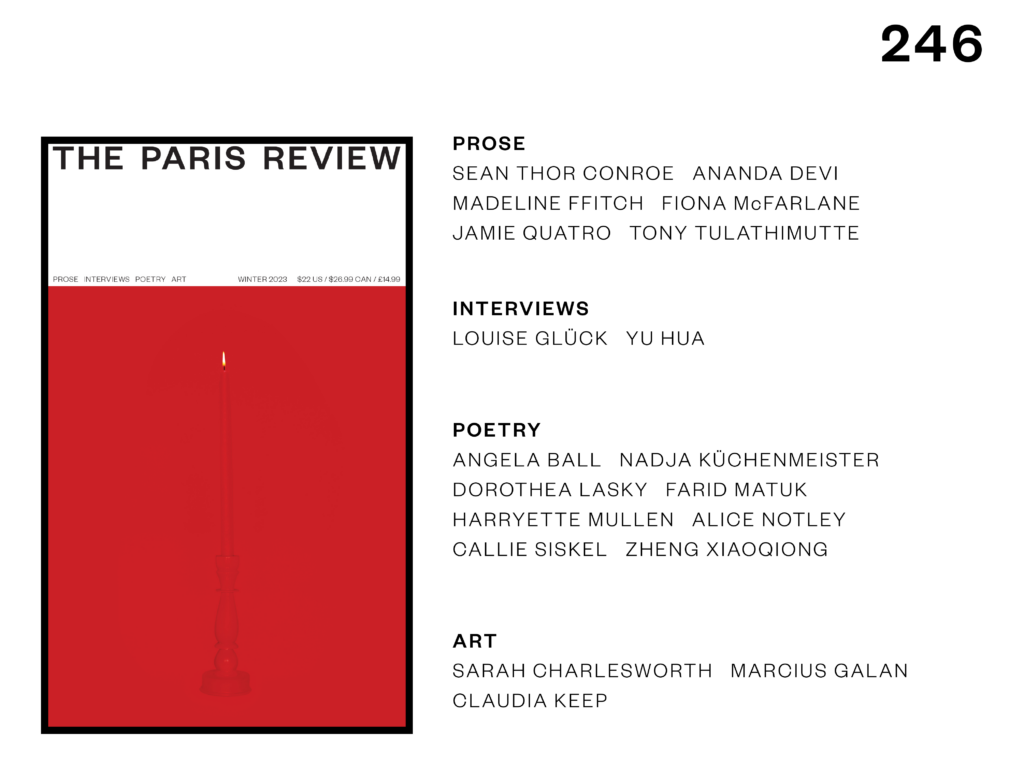

Usually, on the date that a new issue of The Paris Review lands in bookstores and on newsstands, you receive a letter much like this one, announcing it and advertising its wares. In these letters, I have made a habit of loosely tying one piece in the issue to another, suggesting that, while The Paris Review is almost never put together with a theme in mind, some concern might have unconsciously risen to the surface as the editors made their selections—or even that these selections give a kind of animal unconscious to the magazine itself. This is not one of those letters, in part because it does not seem to me the time for any kind of argument about literature and why it might or might not be important. Also, as far as I can tell, the pieces in this issue share very little in common save their quality and perhaps the fact that they each represent, in some form, a quest to find out what the world is trying to be and what it is to live in it. In all this, I am grateful to our contributors, and to you, our readers, for accompanying them. As Louise Glück (1943–2023) tells Henri Cole in her Art of Poetry interview in the new Winter issue, “Anyone who writes is a seeker. You look at a blank page and you’re seeking. That role is assigned to us and never removed.”

Emily Stokes is the editor of The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/RVjA4of

Comments

Post a Comment