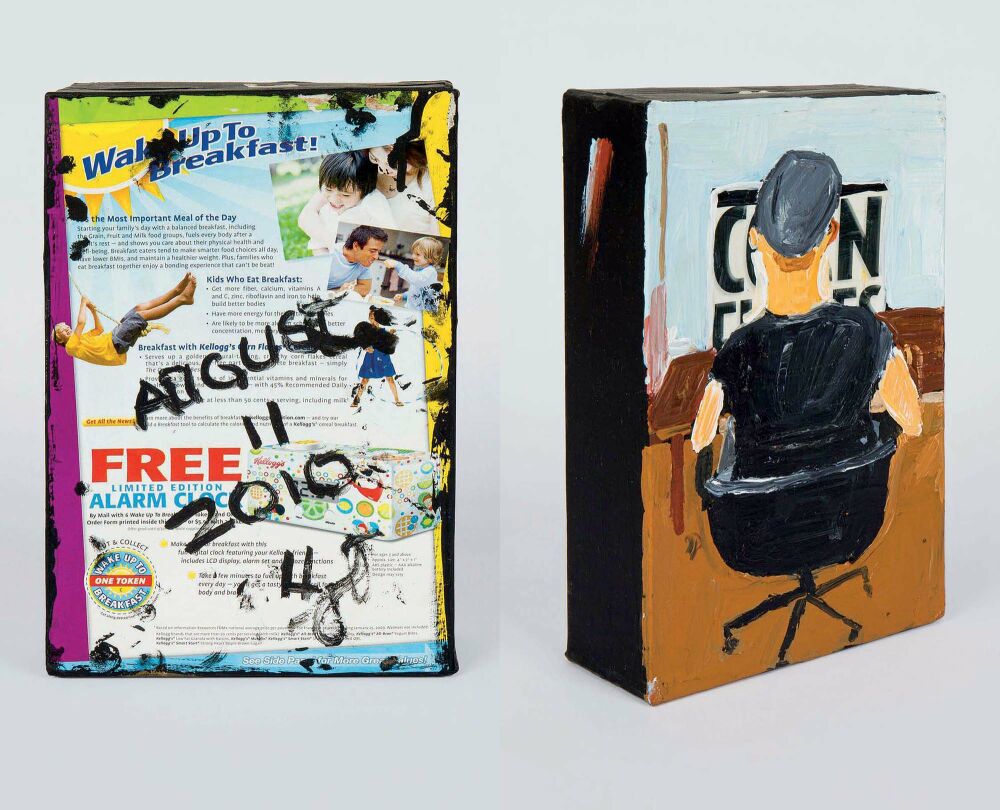

Henry Taylor, UNTITLED, 2010. From Untitled Portfolio, issue no. 243. © HENRY TAYLOR, COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND HAUSER AND WIRTH. PHOTOGRAPHS BY MAKENZIE GOODMAN.

Book that made me cry on the subway: Stoner, John Williams

Book that made me miss my subway stop: Prodigals, Greg Jackson

Book I was embarrassed to read on the subway: The Shards, Bret Easton Ellis

Book someone asked me about on the subway: The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty

Book I saw most often on the subway: Big Swiss, Jen Beagin

—Camille Jacobson, engagement editor

My reading this year was defined by fascinating but frustrating books. Reading to explore, reading for pleasure—sometimes the two don’t converge. In January and February, I battled against Marguerite Young’s thousand-plus-page Miss MacIntosh, My Darling, reading a pdf of it on my computer (why did I do this? I honestly don’t know) and developing a (hopefully temporary) eye twitch in the process. Among other things, the novel is about a bedridden woman in a decrepit mansion experiencing vertiginous opium hallucinations for pages on end. I’m glad I read it but I’m not sure I would recommend it. Speaking of opium, I also finally finished Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria, another kind of fever dream (originally written for money, it’s a mishmash of autobiography, philosophy, and outright plagiarism) that is both completely bonkers and a foundation of modern literary criticism—in it, Coleridge coined the term “suspension of disbelief.” One early reviewer of it expressed “astonishment that the extremes of what is agreeable and disgusting can be so intimately blended by the same mind.” Maybe I relate to this more than I’d like to admit. But a primary purpose of these lists is to give people ideas of what they might enjoy, more than what they might profitably suffer through. So, these books gave me pleasure this year: among others, Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Beginning of Spring, Elspeth Barker’s O Caledonia, Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, Hannah Sullivan’s Was It for This, Gwendoline Riley’s First Love, Dorothea Lasky’s The Shining, and Edward P. Jones’s The Known World. I learned a lot from all of them, too.

—David S. Wallace, editor at large

The text that looms largest in my mind this year is Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette. The novel first appeared in the U.S. in 2020, but it reentered the public consciousness this fall when the organization Litprom, citing the war in Gaza, canceled an award ceremony for the novel. Over a thousand authors formally rebuked the decision. Meanwhile, Israel’s genocide of Palestinians continues, abetted by U.S. funds and rhetoric; since October 7, as of this writing, Israel has murdered over 18,200 people in Gaza and the West Bank.

Minor Detail is a fictional telling of true events—the documented rape and murder of a Bedouin girl by Israeli soldiers in the Negev desert, in the summer of 1949. In the first half of the novel, Shibli imagines the day-to-day activities of the commanding officer in the lead-up to and aftermath of the girl’s capture. In the latter half, Shibli fast-forwards to the near-present, narrating from the perspective of a Palestinian woman who has become fixated on the girl’s story and travels out of the West Bank—with a borrowed ID card that will allow her passage through the intervening military checkpoints—to research the crime. I am especially interested in the rote style of the first act, in which acts of violence bleed together with the mundane. Shibli meticulously describes, for example, the officer’s obsessive daily washing routine, including shortly before the execution of the girl:

He took the towel, dipped it in the bowl, rubbed it with the bar of soap, and passed it over his face and neck. Then he rinsed it, rubbed it again with the soap, and wiped his chest and arms. He rinsed it, passed the bar of soap over it again, and wiped his armpits. Then he rinsed it, rubbed more soap on it, and wiped his legs, without removing the bandage from his thigh. When he had finished wiping down his entire body, he rinsed the towel once more and hung it where it had been before.

The effect is hypnotic. The style makes even brief distraction feel impossible. I admire Shibli’s refusal to abbreviate action, the patience and fortitude with which she illustrates the minutiae that surround and constitute violence.

—Spencer Quong, business manager

Early this year I was having a really bad kind of January week that I ended abruptly by booking a next-day ticket to Vegas and an Airbnb in a nonplace called Pahrump an hour outside it, which ended up being the most fateful experience that a sequence of “Price: Low to High” algorithms have ever conjured me into. The very existence of this town—really just a sprawl of chain-link fences dividing the desert into homes—seemed to me miraculous, as did the random act of free will that had led to my own presence in it; perhaps it was this combination that gave my time in Pahrump the feel of a fateful transformation. Or maybe I had to go to Pahrump in order to find The Pahrump Report, Lisa Carver’s extraordinary diary of a journey uncannily similar to my own: a woman, just turning up, in the loneliest, loveliest of places—this “bowl of endless time.” There she finds lots of interesting people, and funny situations, and love, and freedom. (I also recommend its sequel, No Land’s Man, her diary of travels in Botswana and France.) Carver’s prose, totally unmannered yet deeply lyrical, reminds me of the Dixie Chicks’ “Wide Open Spaces”: you can just hear the blue sky in her voice! Her words are like sun on skin, and wind, too; they sound like aliveness. (You can also read Carver write on strip clubs and cancer on our website.)

I also loved: June-Alison Gibbons’s recently reissued The Pepsi-Cola Addict, a cult novel first published in a tiny run when Gibbons was only sixteen, and eclipsed in strangeness only by her own life story. Her protagonist is a classic good boy gone bad—an eighth grader addicted to Pepsi—whose trials and tribulations make for a surreal coming-of-age story as stylistically sweet, sickening, and sparkly as soda (sorry). “There was an elaborate silence.” Like the best of YA fiction—only better—the novel is a wonderful waterfall of awesome similes, weird adjectives, and exuberant alliteration. It’s also genuinely moving: sad and scary in that senseless, nightmarish way only teenagers can feel.

And Kate Briggs’s The Long Form, probably the only recent novel I’ve read that I can say reminds me of Virginia Woolf. The Long Form is about a young mother and her newborn, but really it is about discovering and inventing relations: between these two, intimate strangers; between life and literature; between space and sound and color. Briggs writes the baby as a kind of blooming diagram, an emergent perceptual phenomenon; like the mobile above her bed, “she was pointed and gapped, full and empty, twisting and suspended, spacey and closed. She was DOTS. … She was a retreating ebb, now an unfathered but gathering, persistent flow.”

Finally, the melancholic Time Tells: Volume 1, a study of time—romantic timing, in particular—as it is modulated by digital media, music, and the movies. Masha Tupitsyn does media criticism like no one else. The book, so attentive to form, fully invents its own: philosophy in the style of a meandering personal anecdote presented as a documentary film transcribed onto the page. The chapters range from close readings of the time stamps in Zodiac (2007) to an interview with Tupitsyn’s mother about style in the Soviet Union. My favorite is a superedit of YouTube comment nostalgia: “I’m 14 and I love this song. / Im 9 and i love this song. / Im 41 years old… / Funny how time flies…”

—Olivia Kan-Sperling, assistant editor

I traveled through France in the summer of 2023, and the best thing I read there was a classic Nicoise cookbook recommended to me by a lovely chef from a village in the South. It’s called La Cuisine du Comté de Nice by Jacques Médecin, and, the chef warned me, is usually expensive and hard to find. But it’s worth it for the gorgeous photograph of an orange fish on the cover and the anecdotes peppered with local dialect. Médecin’s central fixation is to return the Nicoise salad to its former glory before commercial success. “What crimes have we committed in the name of this pure and fresh salad?” he implores, in my very rough translation. Never mix tuna with anchovies, as tuna was historically too expensive and rarely used. “And never,” he concludes, “include the smallest boiled vegetable nor the least bit of potato.” Instead, focus on fresh tomatoes and their interplay with other raw vegetables. Since returning to the States, I’ve been living vicariously through Meg Bernhard’s Wine, on her year spent making wine in Spain, and Alice Feiring’s sensorial memoir To Fall in Love, Drink This. Feiring pairs each chapter with a wine, and I’m tempted to drink my way Julie and Julia–style through her book. A favorite I’ve had so far is Bénédicte et Stéphane Tissot’s trousseau called Singulier, which Fiering describes as “a charming innocent who went off to the Sorbonne, smoked fiendishly, danced with frenzy, and yet could perform a flawless pirouette.”

—Elinor Hitt, reader

The baby arrived in early January, and I spent more of his first six months of life reading than I expected to. You can read (smallish books, mostly) with a baby asleep on your chest, or while feeding him a bottle, or while you’re jittery and awake after ten cups of coffee in the middle of the night when you need to be sleeping.

I read Homo Faber by Max Frisch, a fun incest / “age of the crisis of man” novel by my current favorite (by default) Swiss writer. I loved Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex by Oksana Zabuzhko, recommended in an Elif Batuman essay about rethinking the Russian classics, a piece with which I otherwise found myself in pleasurable but fundamental disagreement. I fell completely in love with Beer in the Snooker Club by Waguih Ghali and became very depressed when I learned it was the only novel he published before his early death. So I read Don’t Look at Me Like That by Diana Athill, in which Ghali is fictionalized as a disagreeable Egyptian student, and was grateful for Athill’s dry wit and perfectly calibrated storytelling.

In the spring, my friend Christine gave me a long list of Fassbinder movies to watch, which led to our household being taken over by sadistic German melodrama for two months, and to my inhaling Ian Penman’s Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors, which I wished was a thousand pages long. I read A Foreign Woman and The Suitcase by Sergei Dovlatov and reconfirmed that Dovlatov was definitely the funniest Cold War–era Russian Armenian novelist. I finally overcame my fear of Daša Drndić’s sparsely voweled last name and read her novel Battle Songs, which was so excellent I went out and bought three more of her books, none of which I read. I read The Company She Keeps by Mary McCarthy and just would not shut up about how great it was. I listened to like five Annie Ernaux audiobooks narrated by Tavia Gilbert and I can’t imagine even the author herself doing a better job of reading her work, though admittedly I do not speak French.

When my self-directed “parental leave” ended, my reading became far less focused due to a deluge of student work and (ahem) pieces to consider and edit. These jostled for time with the harrowing one-two literary true-crime punch of A Thread of Violence by Mark O’Connell and This House of Grief by Helen Garner. Dayswork by Chris Bachelder and Jennifer Habel was the perfect book for a subdivided brain—a lovingly curated smorgasbord of Melville arcana lightly masquerading as a pandemic novel. Grete Weil’s story collection Aftershocks felt like ideal autumn reading: sharp, short narratives of characters who avoided or survived the Nazi death camps but left parts of themselves behind in the carnage. In recent days, I’ve been reading the newish translation of Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed, since a couple of (very literate!) friends asked whether we named our son after him. We didn’t, and I am in no danger of finishing it before his first birthday.

—Andrew Martin, editor at large

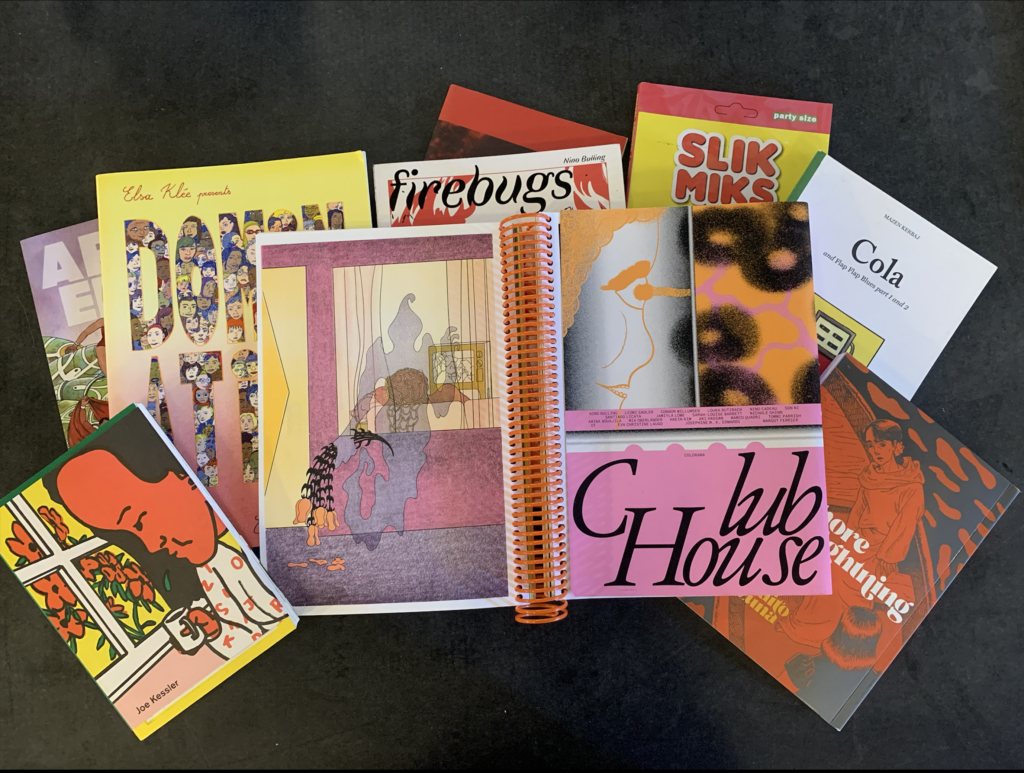

On a recent trip to Berlin, I visited Colorama, a small, community-focused publishing house and Risograph printing studio producing some of the most beautiful and exciting comics in the world, including my favorite book I read this year: Nino Bulling’s Firebugs, an unusually nuanced story of transition delivered in quietly incandescent dialogue and striking visuals—all black and white, with red borders and text, printed on both glossy and matte paper. At the storefront-slash-workshop, I discovered a number of other treasures, such as Melek Zertal’s Fragile, Max Baitinger’s Jazz Night, and an excellent perpetual calendar featuring work by twelve different artists, which I look forward to using, well, in perpetuity. A few days before that, I’d stopped by Hopscotch Reading Room (whose Instagram is worth following wherever you are in the world), where I spent several trancelike hours eavesdropping on other patrons seeking books and comrades. As the owner, Siddhartha Lokanandi, paced the store on a protracted phone call with a publishing house, trying to replenish his stock of Edward Said, I pored over several stacks of the recommendations he’d pulled for me, conjuring them from here, there, and everywhere as if by magic: a manifesto by the French anarchist collective Tiqqun; a Russian lesbian monster novel of the early twentieth century; poetry by the Moroccan communist Saïda Menebhi, who died in prison at twenty-five; and rollicking comics by Elsa Klée, Mikkel Sommer, and Mazen Kerbaj. Other comics I read and loved this year were Bishakh Som’s speculative short stories in Apsara Engine, and her funny, delicately drawn memoir-of-sorts, Spellbound; Joe Kessler’s kaleidoscopic Windowpane and The Gull Yettin; the undersung manga artist Nazuna Saito’s Offshore Lightning, translated by Alexa Frank; and Dirty Thirty, an anthology of selections from the past three decades of the very fun Slovenian comics magazine Stripburger.

On the prose fiction side of things, James Frankie Thomas’s Idlewild—a post-9/11 tale of refracted queer and trans longing, teenage drama club rivalry, and ill-considered fanfiction projects hosted on LiveJournal—might have been the first novel to keep me up all night since high school. I was delighted, too, by Hannah Levene’s Greasepaint (forthcoming from Nightboat in February), a joyously eccentric portrait of a community of lesbian musicians in fifties NYC, often told in long stretches of quickfire conversation. And working on our new Art of Fiction interview with the Chinese writer Yu Hua introduced me to his sly, piquant storytelling, from the early Kafka-inflected stories of The Past and the Punishments (translated by Andrew F. Jones) to his most famous novel, To Live (translated by Michael Berry), in which a wealthy ruffian of the sort who remorselessly beats his pregnant wife and impels servants and prostitutes to piggyback him around town gambles away his family fortune and spends the rest of his life repenting. It’s a bleakly funny—and wrenching—saga that spans the Chinese Civil War, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution. “Back then we didn’t have tissues, and in the end what I had to do was wrap a towel around one of my hands, wiping my face with it and writing with the other,” Yu Hua tells Berry, his interviewer, of his time working on the book in the nineties. “I think if a writer can’t even move themselves they probably won’t move their readers.”

—Amanda Gersten, associate editor

For years, Maryse Condé’s I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem beckoned me. In the spring of 2023, I responded. A strange and powerful book, made somehow less strange by reading about the author’s magical relationship with Tituba—one of the first people to be accused during the Salem witch trials. Though she died more than two centuries ago, Condé says Tituba reached her from the beyond to tell her story.

In summer, the novelist Elizabeth Taylor entered my life with Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont, which I adored. While I loved Tituba’s anticolonial tell-all, I also have a weakness for crisp British understatement, detached third-person, and postimperial drear. Angel was equally great.

They say New York is book country, and I think what they mean is, sometimes a massive ad campaign for a Halloween TV show called Five Nights at Freddy’s reminds you that you’ve never read Penelope Fitzgerald’s At Freddie’s (the one about the school for child actors), and you go to your local library and get it and gulp it down: a classically Fitzgeraldian, life-affirming cocktail of gentle tragedy and wry humor.

My winter read is Sigrid Undset’s Olav Audunssøn tetralogy, which I actually haven’t read any of yet, because I just learned, with great excitement, that it exists, and has recently been translated into English by Tiina Nunnally. Undset is best known for her Kristin Lavransdatter trilogy, which my mom turned me on to some years back, and which, like Olav Audunssøn, follows a single character’s life in medieval Norway. I can’t wait.

—Jane Breakell, development director

I got laid off in the spring, which put me in the mood to resolve some unfinished business. So I finished several collections of which I had only ever read a couple stories. This was a largely fruitless task, but it did give me Lydia Conklin’s brilliant Rainbow Rainbow, which features characters worried they are too old, too young, too out of control, and/or queer but not queer enough. Summer brought several pastel-hued issues of the monthly magazine One Story, including Vauhini Vara’s chilling story “What Next,” a portrait of single motherhood, and Jenn Alandy Trahan’s chatty “The Freak Winds Up Again,” an ode to dirtbagging around Buffalo Wild Wings and baseball diamonds. In the fall, determined to make the most of the lingering warmth, I grew obsessed with both my bike and reading books that fit in my smallest, most bike-friendly bag; Kathryn Scanlan’s Kick the Latch, excerpted in our Winter 2022 issue, was a standout in that category. Now, hunkering down for the winter, I’m reading Jean Baudrillard’s America and missing cold snaps in the California desert.

—Izzy Ampil, intern

2023 will go down in my mind as the year I read Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. I was lured to it over an afternoon spent watching my friend Simone peal with a gossipy sort of laughter every few minutes as she read it herself. As soon as I picked it up, I felt more in cahoots with Anna Wulf—whose existential disillusionment has turned her away from love, a career as a writer, and the British Communist Party—than I ever have with a fictional character. By the time I put it down, months later, I was both in love with her and utterly convinced by the portraits of heterosexual doom scrawled across her diaries (the components of the eponymous notebook). My recollection of Lessing’s work is still changing—especially now, at what feels like an apex of the new decolonial epoch, her studies of the Western left beneath the long shadow of McCarthyism ring less like a lesson in history than a portent for a recursive future. Anna seems to believe, or seems to want to believe, that political hope, if not romantic companionship, is a solution to the solitude at the bottom of being alive. Maybe the most basic and profound affirmation the author conveys through Anna is that this kind of hope is not incompatible with fiction—that in fact, it is fiction. As Lessing says in her own introduction, the “second theme” of her novel is “unity.” What is unity, I wondered this year, if not recalling the laughter of a friend and knowing at last exactly what had been so funny?

—Owen Park, reader

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/lJzXTDA

Comments

Post a Comment