My first brush with Derpycon lore—and by lore I mean its legally enforced code of conduct—was a scroll through its extensive weapons policy.

“LIVE STEEL,” the website went, “is defined as bayonets, shuriken, star knives, metal armor—including chain mail.” Studs on clothing constituted a fringe case, subject to approval by convention staff. This precaution was not due to fear of terrorist attacks but to the preponderance of weapon-wielding anime characters, a popular costume choice among attendees. The rules, I imagined, had been set in response to years of disastrous horseplay, yaoi paddle hazing rituals, and airsoft-gun-as-ray-gun mishaps. Thankfully everyone on the registration line ahead of me had gotten the memo, and their cardboard scythes buckled innocuously.

Derpycon was billed as a three-day, all-ages, “multi-genre” anime, gaming, sci-fi, and comics convention for nerds of all stripes. It boasted “panels, concerts, video gaming, cosplay, vendors, dances, LARPs, artists, and so much more.” The branding this year aligned the convention with the conventional definition of derpyness, meme-speak for bumbling or awkwardness, rather than the more controversial Derpy, a cross-eyed background character from My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic. Any catering to the controversial “brony” (adult male fans of My Little Pony) set would have surprised me. Instead, images proliferated of mishaps: someone running late for the train with a slice of toast in their mouth and “under construction” imagery (the convention’s mascot is the Derpycone). The provisional or half-baked aspects of the con would therefore feel on-brand. The press pass I received contained a charming illustration of a blushing man struggling to stop a train with a large wooden beam in his arms.

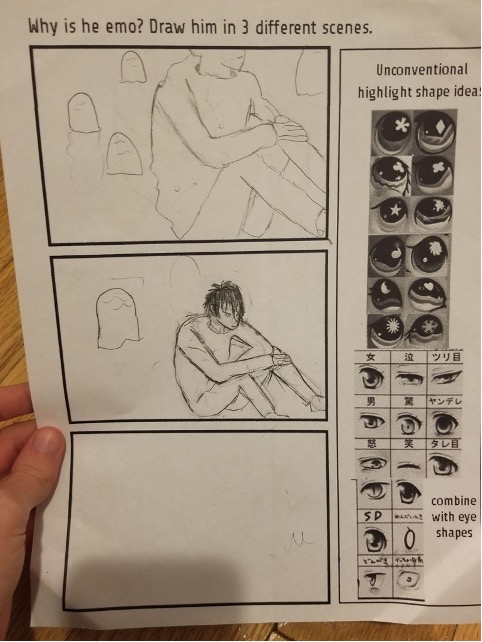

While Derpycon serves many fans, its clear focus is the otaku, or zealous consumers of Japanese popular media. I’d count myself among them, although my own relationship with J-pop became complicated during art school. Like most young illustrators—likely including more than a few teens here in attendance—I first learned to draw in an anime-influenced style that my professors, considering it juvenile, forbade. I adopted it both to spite them and hedge my bets commercially, with mixed success. Now some illustration clients request the anime/manga aesthetic while para-academic institutions still shun it, and AI does it exponentially better than I ever could.

When these conventions started, much of Japanese animation could only reach the U.S. via a niche VHS pipeline, but today the look is arguably the most popular figurative aesthetic worldwide. The casual fanbase is much larger, and the convergence with fine art and high fashion is pervasive, yet the otaku world retains some vestige of insularity and self-consciousness. (Hence the pejorative weeaboo or weeb for its more dedicated constituents—the kinds of hardcore fans lining up sheepishly beside me for weapons inspection.)

Using NijiJourney to recreate the Derpycon press pass in an anime style.

Having made it past registration, I gazed around the tasteful nonspace of New Brunswick, New Jersey’s Hyatt Regency hotel, where Derpycon has been held for three of the last nine years it has taken place. The mob of attendees was distributed throughout the lobby, gently clustering in enclaves over the variegated marble flooring and taking group photos along a glass-sided staircase connecting to the upper mezzanine. In the snack café section to my left, I could pick out a few people dressed as characters from Western media: a Nurse Joker (from The Dark Knight), a Lord Farquaad drag king (from Shrek), and a family of Sims with green plumbob mood indicators above their heads. Despite the heft of its haunch-thighs, a heavyset blue furry had squeezed itself onto a folding chair to pick at a school lunch–style pizza alongside its friends. There were still no bronies, as far as I could discern.

Though I was a lone wolf, I didn’t feel out of place. My own (self-invented) costume transposed cat ears onto a black-and-white laplander hat—which I sought out for the bootleg Vivienne Westwood logo on the side—worn by Shinichi from the manga Nana. I could easily have been a lesser-known character from one of those manga franchises who loses their cat ears when they lose their virginity.

My hat on Aliexpress.

I killed some time drinking a four-dollar Diet Coke and looking over Friday’s schedule on my phone. A number of panels were being held in conference rooms in the mezzanine throughout the day, with names like “Win, Place, Waifu?? Horse Racing in Japan” and “What’s With the Mask? A History of Kigurumi.” At 2 P.M., the “Artist’s Alley” and “Dealer’s Room” of vendors would open to provide a shopaholic diversion. The basement level would hold retro gaming contests into the wee hours. Based on how many attendees were loitering, I doubted it would take long to run the gamut of this programming. I needed a knowledgeable friend to follow around, but a chasmic awkwardness kept pushing me away from my fellow con-goers, like the repellant end of a magnet.

Worksheet I created for my students when I taught a manga/anime-adjacent art class.

It was then that I spied a lone girl laying a hand-painted sign next to one of the hotel’s teetering decorative cairns that read “Let’s be SCHOOL IDOLS.” Resisting my derpyness, I approached to ask her about it.

“Last year,” she confided, “we completely overran the masquerade competition with Idols”—an idol being a Japanese form of commercial entertainer with a fawning parasocial fan base—“so this year they made a separate event for us.” The sign would be part of her friend group’s Love Live! choreographed dance routine at 8 P.M. Like most people in my immediate purview, she was wearing mass-market cosplay garb and a candy-colored wig. These polyester clothes—color-blocked due to the constraints of animation—usually exist stylistically somewhere between school uniform, maid, and babydoll. The most uncanny element of a cosplay ensemble is always the human face, which appears shrunken in contrast to the superstimulus of anime proportions. (E-trailers for cosplay attire now use face filters on models to mitigate this effect.)

Eager to catch the idolatrous vibe, I headed to the next area. On the other side of the lobby’s central hub, one could purchase the signatures of voice actors from English dubs of anime. A voice actor’s signature seemed beside the point to me—perhaps they should have been recording a custom voice memo? But a good number of Derpinas were queuing up, wallets in hand. To the left of the Corellia Temple Lightsaber Guild sign-up desk, I spotted a figure clothed in a babushka, a faux ceramic rabbit mask, a matronly skirt, a leather apron with hatches attached (reminiscent of a utility kilt), and a henley finely misted with blood—they were clearly dressed as Huntress, one of the killers in the multiplayer horror game Dead By Daylight, which I’d developed a casual fascination with during quarantine. I walked up to them excitedly.

Huntress’s appearance in the game is signaled by her eerie Russian folk lullaby; this IRL Huntress told me they’d been using the lullaby recording to scare people in CVS. Desperate to extend our conversation and cement our pop-cultural bond, I tried to describe one of my favorite new DbD killers—the tumorous one with the vagina dentata that embodies the repressed doubts of a utopian community. Do you know it? … But Huntress reached the front of the signature line, so I slithered away.

Rounding the corner, I passed by the station called Cosplay Repair Smith, which was advertised by a styrofoam mannequin head on a PVC pipe affixed to a battered wheeled trunk. Pop-out compartments overflowed with a disorganized array of glues, tapes, hairdryers, hairsprays, barrettes, makeup brushes, screwdrivers, and scrap fabrics, all of which could ostensibly get your One Piece look back in one piece.

My hat hadn’t taken much damage, so I headed up to the mezzanine level to check out the conference room presentations—I had particularly high hopes for “MECHA or Mechanically Engineered Chassis Happen (to be) Awesome.” The mecha subgenre, in which humans wear giant robot suits, is always ripe for transhumanist interpretation—there’s even a journal called Mechademia. One of its writers identified the allegory implied by teen pilots longing for agency and stable identities in the form of sturdy mechanized suits, while another likened mecha to the postwar investment in tech that extends seamlessly from the body. During lockdown, I would sometimes pretend the house I was stuck inside was my robotic exoskeleton, hence my interest in the talk.

Unfortunately, when I walked in, Derpycon’s mechademic was launching into a lore dump of more than a hundred Battletech novels. “Six hundred years is an absurd amount of history to familiarize yourself with, so just focus on the Era that fits you best. Star League Era 2571–2780. Succession Wars 2780–3049. Clan Invasion 3050–3061 …”

The other presentation room was holding a seminar on grooming cosplay wigs. I find the idea of combing hair unpleasant, even on lime green pigtail wigs, so I left quickly.

Nearby, a room labeled Meme Central seemed empty, despite their website promising a slideshow showing everything “from Steamed Hams to those whacky (sic) G.I. Joe ‘historical’ advertisements.” I asked multiple staff members when it would open, giving them the inaccurate impression that I was meme-starved. They were going to ask around.

The next stops on my itinerary were the Artist’s Alley and the Dealer’s Room: in the former, people could sell original fan art, with a strict prohibition on merchandise; in the latter, they could sell merchandise, with a strict prohibition on unlicensed reproductions. Confusingly, these two groups were in the same room, the largest the Hyatt Regency had to offer. But despite the plethora of stalls, most of the Dealer’s Room vendors weren’t offering anything more than the mangas and plushies you can get in the otaku section of Barnes and Noble. More compelling were several walls of gacha capsule machines. They’re similar to the coin-operated bubblegum dispensers outside of barbershops and dollar stores, only the capsules are larger and the toys higher quality. I was stuck deciding between the figurine series of the reptile YouTuber @WANIVSPBAO, tempura-fried yōkai (traditional Japanese demons), and plastic cups of multicolored reproduction popcorn. Like many otaku collectors, I’ve always enjoyed the antisublimity inherent in miniaturization. Nothing overwhelms; everything can be understood, patiently recreated, and added to the dollhouse.

Like the Dealer’s Room, the Artist’s Alley catered primarily to fans of mainstream Japanese franchises. These digital prints and tchotchkes featured the same characters and franchises as the merch, just produced in small batches, with spit glue. There were little Pokemon in succulent garden dioramas that spilled out of Gameboy shells, laser-cut Pokemon earrings, and custom plushes of less popular Pokemon. The prosaic digital paintings of backlit Pokemon inspired a familiar heaviness in my heart—wasn’t this exactly the kind of mood lighting that AI image generators would excel at?

The best use of Pokemon intellectual property was a taxidermist selling shadowboxes of Pokemon cards with real bugs glued inside of them, standing in as the creatures. A “Leavanny” featured a walking leaf bug, one of the most immaculately camouflaged species in the world. A cicada shell from a poorly-timed breeding cycle benefited from the rebrand as a “Shedinja.” Its final form was the green-and-yellow winged “Ninjask,” fanned out in its fearful symmetry.

“What most people don’t realize,” the vendor commented, sagely, “is that Pokemon are bugs.”

The vendor, who had a warm, avuncular manner, turned to attend to a customer buying a cluster of skunk tails. “My nephew and I got these from the swamps,” he added—showing us city slickers just how rural Jersey can get. I moved on.

On my way out of Artist’s Alley, I asked the woman selling pride-flag crochet hats what the peach checkered one was, hoping it represented a sexuality I hadn’t heard of (a type of gastrogender?), but no. Everything adult-oriented would be outsourced to the twenty-one-plus Shenanicon.

My energy had begun to flag. I wanted to talk to the Mario Kart banana peel, but she slipped away. In an attempt to recharge, I took inappropriately large handfuls from the Puffin promotional candy bowl while the well-to-do suburban furries around me scoffed.

My last big stop was the Gaming Room, where at least thirty CRT TVs from the not-so-recent past were lined up on long, black-clothed tables, hooked up to gaming consoles inside of wireframe animal cages (as an anti-theft measure for rare older games, an attendant told me). This area had been subcontracted to another gaming convention, “A Videogame Con.” They were holding off-the-books tournaments of multiplayer classics (Mortal Kombat; Mario Kart; Super Smash Bros) over the course of the weekend. I’m reminded of a time when I inexplicably wanted to join my school’s Game Design Club, and watched a number of presentations by game developers. I learned that the frenetic visual flair of many of these titles is influenced by a “cursed problem in game design,” namely that weaker players in multiplayer fighting games could always gang up on stronger players, requiring the games to incorporate elements of randomized chaos to deter such strategies.

There was also a gorgeous array of maximalist Japanese arcade rhythm games and pinball machines towards the back of the room, schlepped from Maryland by an organization called Save Point. I find rhythm games (most famously, Dance Dance Revolution) to be among the most dazzling interactive design objects ever made. Like opera, they are an attempt at Gesamtkunstwerk, the synthesis of all art forms. At their most effective, these games calibrate the eyes, ears, and reflexes into a 999-b.p.m. flow state of ordered chaos. Most follow the same formula—the player hits buttons as notes float in sequence across the screen—but the rhythm games here had novel modes of interaction, each providing satisfying haptic feedback when you hit or hold a note appropriately. Loveliest of all in this room was Taiko no Tatsujin, a ceremonial drum rhythm game. This cabinet featured two chubby taiko drums mounted on decorative stands. An impatient Chainsaw Man asked to play alongside me. We confidently lifted our mallets together, and the adorable drum-dog mascot goaded us on as the Vocaloid song I’d chosen launched into its frantic groove.

Museca cabinet during play.

Around six thirty, back in the lobby, the mob energy was beginning to wane. I had abandoned any pretense of making friends by this point. I was kicking back for a while in the lounge area to check my email when a man with a working TV as a head and a blue pinstripe suit asked me to take his picture. He told me he was screening The Amazing Digital Circus, which turned out to be a YouTube series in which a denture-headed AI ringmaster tortures a bunch of people trapped in wacky-PoMo avatar bodies. I remembered a friend who’d been fired from Netflix telling me that the only platform Netflix fears is YouTube, which made sense—Circus was the only new Western series I saw con-goers stanning. Biting back my illustrator’s hatred for AI of all kinds, I took his photo, before running away.

Returning to the taxidermist’s table, I was surprised to find that no one had bought any of the Pokemon “cards.” I liked their insinuation that nature really is a magical world of pocket monsters (and that the world, by extension, is a massive multiplayer game). The vendor hadn’t sold the bats signed by famous actors who played vampires either. But one item was missing from earlier this afternoon: the creepish little leech and syringe, mounted on a blood-splattered piece of card stock.

“Yes, the leech. Every con we sell a few leeches. I don’t know the reason,” he said. Maybe it was because they weren’t Pokemon, or maybe it was because deep down, they were.

After some more dawdling, it was finally time for the day’s culminating event: the Derpy Idol Showcase, which the girl with the sign had told me about earlier. At 8 P.M., the crowd filed into the Regency’s ballroom in an orderly fashion, and I was reunited with all zero of my new friends. The lights dimmed, the lip-syncing track came on at 999 b.p.m., and in an instant, fake idols turned real.

The idols take to the stage.

The performance was an imitation of the poised Japanese superstars, lip-synching to their songs and donning their matching outfits. I didn’t think the dances were too different from TikTok dances, in their moves or affect. I wanted to see something stranger than a suburban teen talent show. But evaluating things on a barometer of obscurity is my own tic, and I admit: the show was well-done. The girls’ poise and charisma was impressive and the choreography they’d practiced in the parking lot well-rehearsed. This is New Jersey excellence! I, Montclair-born-and-raised, told myself. The high-pitched polyphonic vocals bubbled with girlish exuberance over a raging beat. (Grimes was once a cosplayer too, if that isn’t obvious.)

After the performance, I decided to leave Derpycon, forgoing the “How to Rizz (For the Lonely Weeb)” seminar at 10 P.M. This is a crowd where DM stands for Dungeon Master, I thought to myself, pithily. But I’m a nerd, too. My excuse is that it’s in my blood: one of my ancestors, Commodore Mayo, was credited with inventing the character of Uncle Sam as a figure of speech in one of his naval logs. I just wish my grand-uncle had the foresight to make him cuter, have different colored eyes (one blue, one red), and carry a scythe.

Generated with NijiJourney.

Liby Hays is a writer and artist living in New York. She is the author of Geniacs, a graphic novel about a poet who enters a hackathon, and a codesigner of Conspecifics, a research-practice kawaii streetwear brand.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/dylBLI5

Comments

Post a Comment