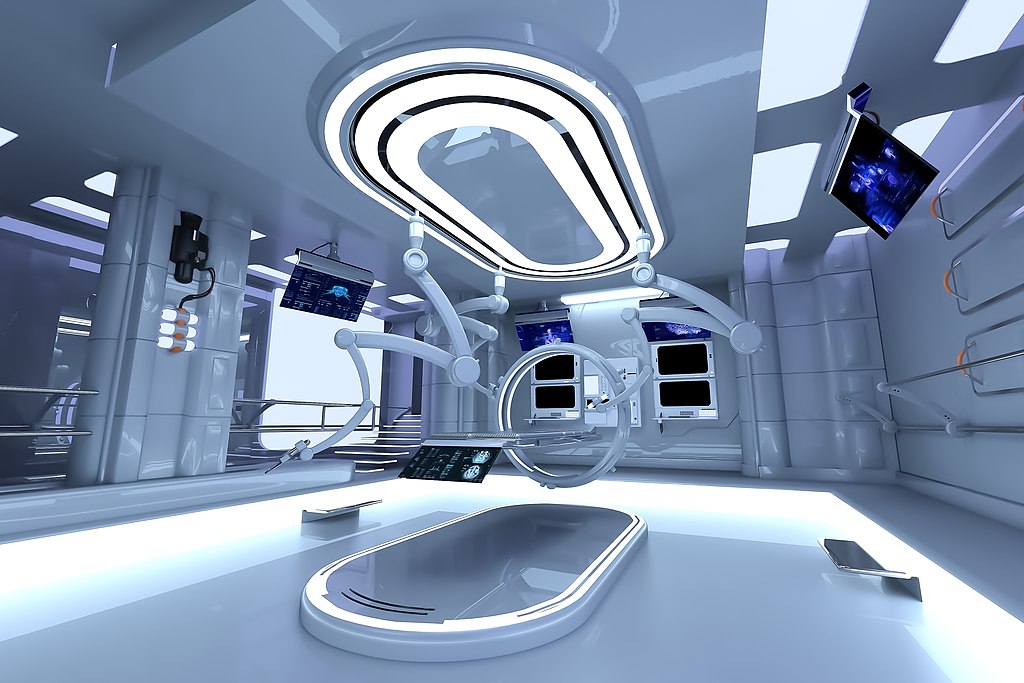

Digital artwork of a science-fictional surgery room by alan9187, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Hospitals play a big role in Yu Hua’s life and fiction—his parents were both doctors, he grew up in and around hospitals as a child, his first job was that of a dentist, and hospitals would later frequently appear in his work as sites of violence and trauma. Yu Hua first made a name for himself in the eighties with a series of dark, violent, experimental short stories, but over the course of his career, his writing became more conventional, earning him a broad readership and fame in the process. But what if Yu Hua had gone the other direction? What if he had gone darker, stranger, more experimental? If one is looking for someone to inherit the lineage of Yu Hua’s early experimentalism today, I would point them to Han Song’s Hospital trilogy, which not only shares a fascination with the medical setting but also presents an unflinching look at the violence lurking just under the surface of the everyday. It is no coincidence then that, during a recent interview I conducted with Han Song when he was speaking of his formative influences, he told me: “I was particularly fascinated by Yu Hua at that time and even imitated him.”

Comprised of three full-length novels, Hospital, Exorcism, and Dead Souls, the trilogy begins in a fairly conventional manner. Yang Wei, a forty-year-old government worker who moonlights as a songwriter, is struck down with a bout of debilitating stomach pain after checking into a hotel in C City during a business trip. The pain is so horrific that Yang Wei passes out, awakening three days later to find two female employees from the hotel taking him to the hospital. From there, Han Song takes us on a Kafkaesque journey where the protagonist undergoes countless tests, procedures, and operations. He is sent from one wing of the hospital to another, waiting in long lines, vying for the attention of any one of the mysterious doctors who inhabit the hospital, and yet seemingly unable to get any information, let alone a diagnosis. The longer he stays in the hospital the more lost he becomes, until reality itself seems to unravel around him and he descends into a labyrinthine nightmare of the strange.

Translating the trilogy has fully consumed, even haunted me, since 2020. Reading it is a challenging experience and certainly not for everyone. The series contains frequent descriptions of pain, rape, murder, suicide, and cannibalism, but even more disturbing, in a way, is its unconventional use of language, unusual structure, and shifting perspectives (Hospital is written in third person, Exorcism in first person, and Dead Souls in second). It contains dense references to medical terminology, scientific history, Buddhism, Christianity, Japanese pop culture, and classic literature and philosophy from Plato and Aristotle to Kafka and Sartre, with plenty of veiled references to the political reality of contemporary China along the way. The series is categorized as “science fiction” by booksellers in China and abroad, but that is misleading. For a while, I described it as a mash-up between science fiction, horror, suspense, social realism, and avant-garde literature; think a hallucinogenic David Cronenberg film written by Franz Kafka and set during a Chinese politburo meeting. But I’m not sure if even that description does the series justice. Over the past three years, as I have slowly worked through the translation, my understanding of the series has evolved. I am always discovering new layers of meaning hidden within the book’s devilishly complex narrative.

Of course, one reason for the literary transpositions presented through the series might be found in China’s current censorship standards. With a long list of “sensitive” topics that Chinese writers are forced to avoid, the “cultural no-fly zone” for writers and artists in China has become increasingly expansive. The fact that a series like this was published at all is due in large part due to the brilliance of Han Song, who has contorted his critical vision to the point it is unrecognizable to many readers (and Chinese censors). But if readers peel away the façade of absurdity, they will quickly find uncanny reflections of and critical insights into the reality of China today. Calls to “tell the good hospital story” will certainly remind readers of Xi Jinping’s instructions to “tell the good China story”: the violence and hospital uprisings echo the Cultural Revolution; references to hospital “reform” echo Deng Xiaoping’s Reform Era; and although the word China is seldom mentioned in the entire trilogy, “the hospital” can be read as a stand-in for the Chinese Communist Party or the nation itself. This is not dissimilar to what Yu Hua—and other writers like Ma Yuan and Can Xue—did in the eighties with their own experimental fiction. But Han Song has taken things much further. The violence is pervasive, the hospital is all-consuming, and its permutations never end. This calls on readers to take an active role in decoding the novel to reveal its litany of horrors and flashes of the sublime.

At times, I have wondered if the whole thing was composed by an AI program gone haywire. Perhaps it is best to describe it with the Chinese term qishu, which is alternately translated as a fantastic, strange, or wondrous book. Han Song has spoken about the influence of Studio Ghibli films on his work and his attempt to render their marvelous, unbridled imagery in a literary form. Having finally completed my translation of the final volume, I increasingly think of the trilogy as a dream, or a nightmare, taking place on a deep subconscious level; it is meant to be experienced more than intellectualized or analyzed. But for now, Han Song’s hospital continues to haunt me.

Michael Berry is the author of Translation, Disinformation, and Wuhan Diary: Anatomy of a Transpacific Cyber Campaign and the translator of novels by Yu Hua, Wang Anyi, Fang Fang, and Han Song. His interview with Yu Hua appears in our new Winter issue, no. 246.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/mFB8iQ1

Comments

Post a Comment