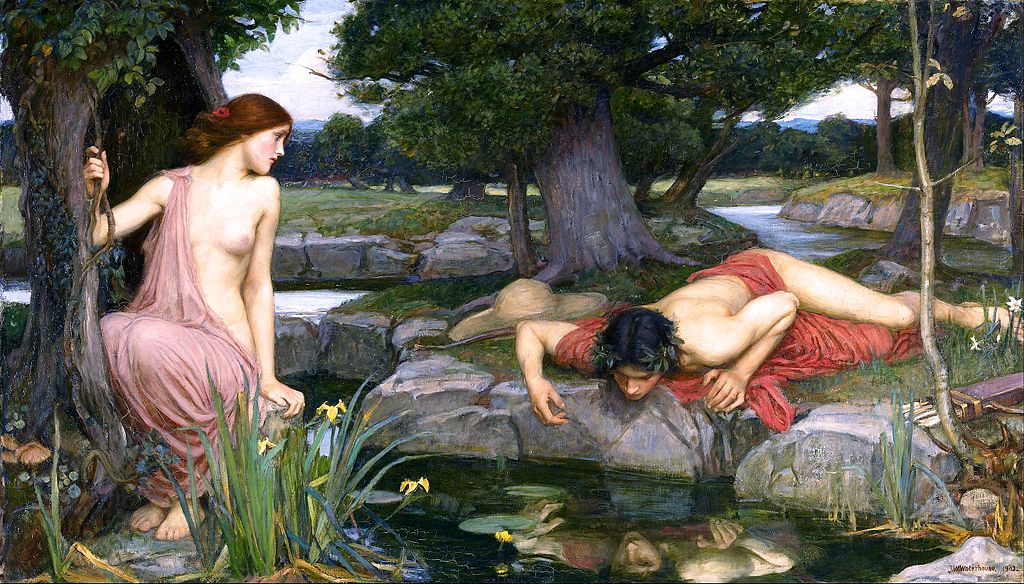

John William Waterhouse, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

When I read Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies, a novel about an interpreter at the International Court of Justice, I found myself underlining every page. Perhaps the identity crisis of the narrator—“I was repulsed, to find myself so permeable”—had transferred to me. Or perhaps the clarity of her sentences left me defenseless. I was instantly immersed. Like all of Kitamura’s fiction, Intimacies is about the psychic effects of inhabiting another person’s mind. The novel explores the narrator’s complicity as she voices the words of a war criminal and the personal crises of those around her. Can channeling others shape (or erase) our sense of self? And how does private grief deepen or prime a precarious selfhood? Even when she interprets the words of a victim, she concedes “the strangeness of speaking her words for her, the wrongness of using this I that was hers and not mine, this word that was not sufficiently capacious.”

My poems in the Winter issue of the Review grapple with the boundary between self and other, image and reflection. I wrote “Echo” not long after finishing Intimacies. Echo, whom the goddess Hera silences, is left repeating the last words of the object of her love, Narcissus. The effect is a kind of trailing-off, a depreciated self. Though Kitamura’s narrator also feels depreciated (“I realized that for him I was pure instrument”), the novel’s stunning end reconstructs the first person. Intimacies is that rare novel that, fittingly, reverberates in your mind.

—Callie Siskel, author of “Narcissus,” “Echo,” and “The Concept of Immediacy”

I came back from London on a miserable winter day, feeling fluey and gray, filled with an end-of-year, end-of-era angst that I saw reflected in the heavy skies and the mountains looming, gloaming, above Geneva.

Close curtains and shutters, doors and windows, pour a glass of wine and go straight to bed, I told myself. Play Scrabble against the computer. Do the Guardian crossword. Forget that the world is breaking apart at the seams. Forget that it will probably only get worse. Forget the novel by Velibor Čolić that you have just read, which conveys, with so much harsh, unflinching poetry, the stink and putrefaction of a soldier’s life.

And then. Walking into the house warmed by a chimney fire, I was told by my husband that I had received yet another book in the mail, this one from the U.S. I opened the parcel with a sigh, but was still intrigued, as I was not expecting anything from there. And so, it came out, a beautiful, textured orange-and-gold slip case from which peeked an orange-and-gold spine: Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities. A new illustrated edition, from the Folio Society. I took a moment to caress the case and marvel at its sensuality. The book slid out. The cover illustration was dreamlike: two male profiles, facing opposite directions, a river curving in between, a hilly and domed city filling the top of their joined head. Dark clouds above. Another distant city below. I was enchanted. The pages of the book were like silk. I glanced at the various illustrations, all as beautiful, as evocative, and read the first sentence:

Kublai Khan does not necessarily believe everything Marco Polo says when he describes the cities visited on his expeditions, but the emperor of the Tartars does continue listening to the young Venetian with greater attention and curiosity than he shows any other messenger or explorer of his.

Oh wonder! The winter blues (ice blues!) dissipated. The skies cleared. All my senses were ablaze. I opened the card accompanying the book: “ ‘Dear friend’ doesn’t even begin to describe this friendship of ours that’s so much more than friendship! ‘My dear author’? ‘The aunt I never had’? No, the truth is that I like best the word that you used some years ago: complice. Ma complice, chère Ananda, c’est toi.”

The gift was from Jeffrey. Jeffrey Zuckerman, my translator, the one who gave my novel Eve Out of Her Ruins its wings, and who translated “Ice Blue,” published in issue no. 246 of The Paris Review. I was moved to tears. And my mind opened out to the possibilities offered by these invisible cities. The breadth of Calvino’s imagination as he recreated a world of possibilities and impossibilities. Calvino, whose work I love but have neglected to reread in recent years. He writes,

Yes, the empire is sick, and, what is worse, it is trying to become accustomed to its sores. This is the aim of my explorations: examining the traces of happiness still to be glimpsed, I gauge its short supply. If you want to know how much darkness there is around you, you must sharpen your eyes, peering at the faint lights in the distance.

Reading this, I glimpsed a possibility for a novel that I had been toying with in my mind for some time. Not only was Jeffrey’s gift a book by a marvelous writer, but it could also provide a key to a future book of mine.

But most of all, Calvino swept me along and aloft as I read him, to the top of crystal towers or to the bottom of a city, where the depths have the smell of the dead. We need to delve deeper to catch a glimpse of the faintest of lights above.

—Ananda Devi, author of “Ice Blue”

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/WJmGPwp

Comments

Post a Comment