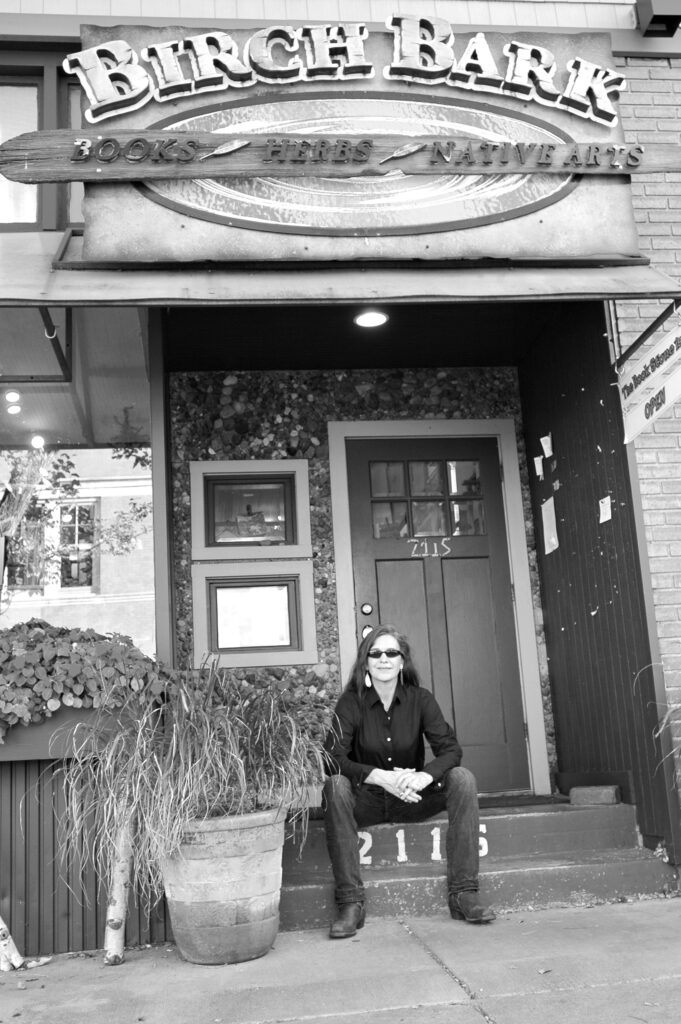

Photograph by Angela Erdrich.

The Paris Review’s Writers at Work interview series has been a hallmark of the magazine since its founding in 1953. These interviews, often conducted over months and sometimes even years, aim to provide insight into how each subject came to be the writer they are, and how the work gets done, and can serve as a kind of defining moment—crystallizing a version of the writer’s legacy in print. Of course, after their interviews appear in our pages, many writers just keep going, and their lives undergo further twists and turns. Sometimes, too, there are gaps and omissions in the original interviews that can become clear as time goes on. This is part of why we’re launching a new series of web interviews called Writers at Work, Revisited. The first will be an interview by Sterling HolyWhiteMountain with Louise Erdrich, who was originally interviewed for the magazine in 2010.

***

Americans have most often viewed Indians through an anthropological lens; the desire to understand us through difference overtakes all else and creates a permanent distance between the seer and the seen. It is the oldest story in America, and over time has exerted such pressure on Indians that we’ve become explainers nonpareil in every facet of our lives—our fiction being no exception. Once you see it you cannot unsee it; the sheer amount of explaining directed at non-Native readers that takes place in Native writing is remarkable. The best of us, though, continue to do what good writers in this country have always done: produce fiction that is more in conversation with the aesthetic lineage of English literature than any particular audience or political question. From the start Louise Erdrich’s writing has had this quality, and her large body of work is a lodestar for the Native writers who have come after her, showing us how to write past America’s ideas and expectations about Indians into places both more tribally specific, and more human. Her work acts as the primary bridge between the writers of the Native American Renaissance—N. Scott Momaday, James Welch, Leslie Marmon Silko—and the explosion of Native writing currently taking place. Her characters, regardless of their culture or history, remind us of that great paradox of humanity, that we are all profoundly different, and very much the same. Perhaps most importantly her work reminds us that good fiction is made up of good sentences.

I had expected, because of her lack of public presence, to meet a writer who was something of a recluse. When I finally made it to Minneapolis, however, I found her to be open, self-effacing, funny, generous, and troublingly up-to-date on the politics of the moment—in both America and Indian country. She was also familiar to me in that way Indians are regardless of what tribe or geography they come from. She spends most days, when she is not traveling to various parts of the Midwest for familial and ceremonial reasons, working in her bookstore, Birchbark Books, one of the finest independent bookstores in the country. The store is the only one of its kind: owned and curated by a major Native writer, run by Native employees, where you can find a copy of Anna Karenina a few feet from abalone shells and sweetgrass. Louise was gracious enough to take time from her usual day of working in the back office to talk with me in the basement of the store.

—Sterling HolyWhiteMountain

ERDRICH

How’s your car? You were having some trouble with it.

INTERVIEWER

I got pulled over last night. I’ve never seen a cop so perplexed. He was skeptical about everything, which I get. I said, I’m moving out to Massachusetts for seven months, and I have to be in Minneapolis tomorrow morning for an interview. Here I am in this old truck I got from my sister that’s full of my junk. I didn’t have insurance. I was going to get it yesterday morning, but I started having engine troubles and forgot all about it. So I’m driving most of the night through endless North Dakota and into Minnesota at forty miles an hour—any faster and the engine would quit. He ended up letting me off.

ERDRICH

I hope you thought your novel out on that slow ride. I remember, when I started out, I was always writing poems about the desperate women in the breakdown lane, which was where I always found myself because I also had an unreliable car, a Chevy Impala station wagon. It would overheat, but a great car.

INTERVIEWER

This is after college? I’d love to hear about how you got started.

ERDRICH

Start the car? If the key didn’t work, I used a slot-head screwdriver and a hammer. Writing? I don’t actually know. I always wrote, then at some point I realized it was the only grown-up thing I knew how to do. After college, I was living in Fargo and got a seventy-dollar-a-month office at the top of a building that looked out on the horizon. That’s when I started Love Medicine, in that office.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a set of problems that belong only to Native writers, and I’ve noticed that Indians often end up working these problems out alone because they don’t have someone to talk with who understands. When I started writing it was hard to find Native writers I could look to. Did you feel that way when you started?

ERDRICH

I like what you said about the set of questions that belong only to us. There were fewer well-known Native writers back then. But there was James Welch and Leslie Marmon Silko, Simon J. Ortiz, Janet Campbell Hale, Paula Gunn Allen, Beatrice Mosionier, and of course N. Scott Momaday. Roberta Hill and Ray Young Bear were poets I admired. Joy Harjo was and is cherished by us all. There were more Native writers when you were coming up—you had Sherman Alexie. And Eric Gansworth—a formidable writer, intelligent and warm. Still, I know what you mean, because it’s not just writers who are Native. It’s writers with your own particular tribal background. Did you find writers online?

INTERVIEWER

Not at all. Because when I first got going, the internet was in its nascent stages … there was nothing! I didn’t know there was such a thing as a Native writer until I read Alexie’s first book, around the time James Welch came to speak in one of my classes at Missoula. You wrote a great introduction to the 2008 edition of Winter in the Blood, which is arguably Welch’s masterpiece. Did Welch influence your work?

ERDRICH

Yes, most definitely. His work still influences me, especially Winter in the Blood and Fools Crow. I met him only once or twice. He struck me as an extremely modest man. As a writer, too, he was able to step aside and let his characters exist on the page free of judgment. His style was never forced, self-consciously artful, or designed to impress. The Heartsong of Charging Elk and Fools Crow are more ornate and language-driven, but his characters are still formidable searchers. I have always been impressed with The Indian Lawyer because, in the character of Sylvester Yellow Calf, Welch wrote about an Indian professional, someone who had come out of a tough background and had been touched with grace, athletically and intellectually. James even gave him a complicated love life and conflicts that were about being Indian but were really in the context of trying hard to be a conscientious human being. Also, since no Pulitzer Prize was awarded in 1974, the year Winter in the Blood was published, I think it should be posthumously awarded to James Welch for that book.

INTERVIEWER

Is being free of judgment important to you as a writer?

ERDRICH

It is one of the most important things.

INTERVIEWER

I’ve noticed that some younger Native writers feel that they’re not supposed to be influenced by non-Indians. How do you think about that?

ERDRICH

To begin with, if you’re not working in your traditional language, you are working in the colonial language, an automatic influence. I can barely speak to a four-year-old in Ojibwe, let alone write in it. But I own the curse and glory of English, a language that has eaten up so many other cultures and become a conglomerate of gorgeous, seedy, supernal, rich, evocative words. There is no purity—that is the great advantage of English. It’s so expressive, so flexible. We have to reverse-colonize English by reading far and wide.

A writer has to be indiscriminate and read promiscuously. I’m influenced by everything I’ve ever read, and I read incessantly, with no regard to genre or what I was supposed to be reading. I’ve read for pleasure, and pleasure for me includes challenging reads as well as novels that have that addictive quality I kind of adore. I’m reading Harlem Shuffle by Colson Whitehead for the second time. And in the past couple of years I’ve read Magda Szabó, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Octavia Butler. Leslie Marmon Silko, of course. Tove Ditlevsen. Olga Tokarczuk. Isak Dinesen, Edward St. Aubyn. A person has got to read Stendhal, Hugo, Dumas, Balzac, Goethe, Woolf, Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Zora Neale Hurston, Flannery O’Connor, and then James Baldwin, Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, Toni Morrison, and of course N. Scott Momaday. I read every Native writer I can find. Right now I’m reading Eric Gansworth and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson. I love Jean Rhys, Wide Sargasso Sea. Angela Carter and her short story “The Fall River Axe Murders,” about Lizzie Borden—I keep rereading that story. It’s deadly and dark and funny. I love spy novels. I’ve read all of Graham Greene, Le Carré. My daughter Pallas just gave me Mick Herron’s Slough House series—catnip. Sometimes you just love part of a book—for me, it’s the first part of Portrait of an Unknown Lady, by Maria Gainza. And wait, then there is Amitav Ghosh—a class of his own. Likewise, Nuruddin Farah. Sorry, I’m being a bookseller.

INTERVIEWER

When I was nineteen, I read On the Road, and I immediately just started writing. I’ve avoided rereading it for so long because I thought, Oh God, it’s going to be awful. But recently I gave it a shot— it was better than I thought it would be. There are some really, really beautiful sentences, that elegiac tone. The thing I didn’t remember is how much talk about Indians there is in that book—and the way he talks about them, or us, is stupid. But I also kind of don’t care because I don’t go to Kerouac for realistic writing about Indians. Can you really enjoy a writer, flaws and all? Are there limits?

ERDRICH

I often like the flaws in books. I suppose it is heretical of me to say that Moby-Dick is flawed, but Melville dropped the relationship with Queequeg to go off in a hundred marvelous directions. There is a hole in the book, and I don’t mind it.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned Faulkner. He showed me a way to write about a place and a history and a people. How has he influenced you?

ERDRICH

What resonates for me in Faulkner’s work is his way of building chains of outrageous circumstance. His aching, damaged characters hook you in the heart; his low-key greedy villains are funny in an appalling way. Spotted Horses is one of my favorite novellas of all time. The image of the South in shocked resentment, sullen and fallen, resonated for me not because the culture of enslavement was anything but depraved, but because Faulkner’s characters are always in contention with history—with a sordid glory, I guess. And now we see that played out here in our country with desperate attempts to cling to a mythical whiteness.

INTERVIEWER

I was at Standing Rock in 2016, and it felt like a war zone. Native people are profoundly connected to the U.S. military—either as part of it or at odds with it. How do you think about that relationship?

ERDRICH

The U.S. military is woven into the history of the conquest of Native people and the wars of extermination. Boarding school history starts with military forts being turned into government boarding schools. Land was taken from Native people for military bombing sites. Tribal corporations use Native preference to subcontract for non-Native military contractors. It goes on and on.

Native people fight in great disproportion to our population. We have the highest serving level of population of any group in the U.S. In the First World War, there were Indians fighting, and we didn’t even have U.S. citizenship. On this subject, Winona LaDuke wrote a terrific book with Sean Aaron Cruz called The Militarization of Indian Country. And then there’s Leslie Marmon Silko’s iconic novel Ceremony, the best novel ever written about the relationship between Native people and the military.

When I went to Standing Rock, the complexity of this relationship was clear. Sheriffs all through the Midwest and West had diverted officers from their forces. The National Guard was involved, so that’s the U.S. military, plus private contractors like TigerSwan, and various community forces were all working at the behest of a multinational corporation. But then, remarkably, U.S. military veterans, including many Native veterans, showed up to support the protesters at Standing Rock. They were standing against their own military.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think there’s some way to change the larger narratives about Indians and Indian country?

ERDRICH

I’d like to see more narratives about the glorious things that Native people do.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever been to the Blackfeet Reservation? That’s where I’m from.

ERDRICH

I have, quite a few times.

INTERVIEWER

That’s where I grew up, right next to the mountains. I’m a little hesitant to use language like this, but they are like our holy lands. Chief Mountain is in the northeast corner of the park and is one of our primary spiritual sites. On the one hand, I grew up with this incredible experience of beauty in the park—hiking, climbing, swimming—and on the other hand, I grew up hearing stories about how the mountains were taken from us. I learned how they were acquired, and it was basically like, You’re either going to sign them over to us or we’re just going to take them. My politics are very sovereignty-oriented … like, fuck, restore our sovereignty, give us our sacred sites back.

ERDRICH

I’m the same. I’d like to go from the nice first step of land acknowledgment to giving back actual land. Within the boundaries of the original treaties, not the ones our ancestors were starved out to sign. My ancestors originated on Lake Superior. I go back there often, and I take in a phenomenal sense of eternity. Mooningwanekaaning, known as Madeline Island, and the Apostle Islands are ancestral homelands, and it burns deep to have them stolen, as all national parks and shores are stolen. In 2017, a fifty-year lease on the north end of Mooningwanekaaning came due and the Bad River Ojibwe rejected a lease renewal or buyout. They needed that money, but they took the land back.

INTERVIEWER

How do you navigate these political issues as a fiction writer?

ERDRICH

I don’t think about politics when I write. I think about the characters and the narrative. My novels aren’t op-eds. Nobody reads a book unless the characters are powerful—bad or good or hopelessly ordinary. They have to have magnetism. If you write your characters to fit your politics, generally you get a boring story. If you let the people and the settings in the book come first, there’s a better chance that you can write a book shaped by politics that maybe people want to read.

INTERVIEWER

You and Natalie Diaz won the Pulitzer in 2021—the first Native people to win it since Momaday in 1969.

ERDRICH

The Pulitzer didn’t go to me—it went to The Night Watchman, a book about my grandfather, Patrick Gourneau, who worked to fight termination. He worked around the clock, supporting his family, running a farm, being a night watchman for the first tribal factory, and galvanizing a movement to save our tribe. After returning from Washington, D.C., he suffered a series of strokes. Our family has always had a great deal of sorrow over his sacrifice. When I found out about the prize, I called my mother and said, “Grandpa won the Pulitzer.” It was very moving to me, to my mother, to my family, my people. And my personal joy in receiving this prize along with Natalie Diaz was pretty simple. It was very moving. All Indigenous people are Anishinaabeg in our language, so let’s just chalk up a win for the Anishinaabeg.

INTERVIEWER

Are there other victories you’ve been chalking up?

ERDRICH

Well, there’s Reservation Dogs, beginning and ending on its own terms. Dyani White Hawk had a piece in the Whitney Biennial. Raven Chacon’s Voiceless Mass was awarded the Pulitzer. Owamni, a Dakota restaurant here in Minneapolis, won a James Beard Award in 2022. I’m not going to pretend these recognitions aren’t important. We have a very different set of motives in our art. We are honoring our politics, our loved ones, our traditional foods, our history, and we’re struggling against over half a century of murderous dispossession and silence. Chacon has said Voiceless Mass is about “the futility of giving voice to the voiceless, when ceding space is never an option for those in power.” And Diaz’s Postcolonial Love Poem is a rapturous stream of intelligence.

We punch way above our weight culturally and politically—think about how many Native women have won political races and taken charge in the last few years. Deb Haaland, Peggy Flanagan, Sharice Davids, Ruth Buffalo, and others. Or charismatic activist-writers like Winona LaDuke. And Native people who lead in entertainment. I’m a big fan of Jana Schmieding and Zahn McClarnon. Add the casts of Reservation Dogs, Rutherford Falls, Dark Winds. Sometimes I feel like we’re fighting for our sovereignty joke by joke, book by book, political win by win, and that’s not even bringing wild rice and the ribbon skirt into the picture. Let ribbon-skirted women rule the world. Don’t you think ribbon-skirted women should rule the world?

Sterling HolyWhiteMountain is a Jones Lecturer at Stanford University, where he formerly held a Stegner fellowship. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and The Paris Review. His story “This Then Is A Song, We Are Singing” appeared in the Review‘s Winter 2021 issue. He is an unrecognized citizen of the Blackfeet Nation.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/4HWuRMC

Comments

Post a Comment