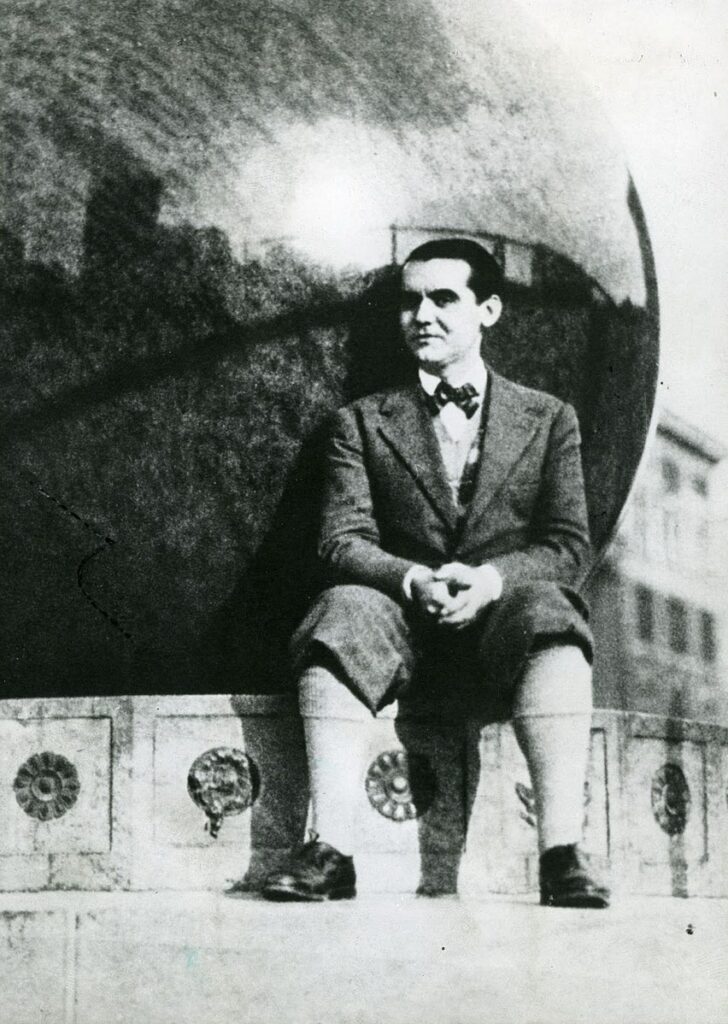

Federico García Lorca at Columbia University, 1929. Public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

For a son of the titular city, reading Federico García Lorca’s Poet in New York is akin to curling into your lover, your nose dipped in the well of their collarbone, as they detail your mother’s various personality disorders. Yes, Federico, yes, my mother is thoroughly racist and takes every opportunity to remind me, her sometimes destitute child, about the silent cruelty of money. “At least you got to leave,” I want to tell him. “Imagine being stuck with her for the rest of your life.” He would likely understand my irrational attachment; after all, he was so consumed by Spain, its art and its politics, that his country would go on to swallow him whole.

Still, it is crucial for those of us with this sort of umbilical tether to unwind it and test how far it might stretch. In June 1929, following a voyage on the sister liner of the Titanic, Lorca arrived from Spain by way of Southampton, England, to New York, a city he would immediately call a “maddening Babel.” The poet was thirty-one, nursing his wounds from a breakup with a handsome sculptor, Emilio Perojo, whom Lorca maintained used him to gain access to the art world. Lorca had also become estranged from a pair of his Spanish friends and contemporaries, Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel, and felt hemmed in by the success of his most recent work, Gypsy Ballads. He wrote, “This ‘gypsy’ business gives me an uneducated, uncultured tone … I feel they are trying to chain me down.” With the help of his parents and at the urging of Fernando de los Ríos, a law professor and friend of the family, Lorca enrolled in a summer program at Columbia University. For the better part of a year, in room 617 of Furnald Hall, and then in room 1231 of John Jay Hall, he would write Poet in New York. The language is hallucinatory and toxic, peyote laced with sulfur: pigeon skulls lie in corners; cats choke down frogs; blond blood flows on rooftops everywhere; tongues lick clean the wounds of millionaires. V. S. Pritchett wrote about the book: “What we call civilization, [Lorca] called slime and wire.”

I visited Furnald Hall on a Thursday in January. It was around 3 P.M. The sky, vacuumed of its gauze, had begun to pale. I went as a guest of a friend who teaches at the university, and both of us promised security I’d leave quickly. Perhaps it was because I was rereading the section in Poet called “Poems of Solitude in Columbia University” or because it was shortly before registration for the winter semester, but every sound in the hallways was harsh and detached—hoarse conversations behind half-closed doors, the thin complaint of de-icing salt underfoot. Room 617 was locked, but 618 was being moved into. With the student’s permission, I examined the room and looked out the south-facing window onto campus. The student asked me what or whom I was searching for. I couldn’t say. I couldn’t rewild the sycamore skeletons that were now clinging to the day’s last light; I couldn’t properly conjure the summer of 1929; but I did wonder if it was from this vantage that Lorca dwelled on his former lover, the supposed careerist.

What I gave you, Apollonian man, was a standard of love,

bursts of tears with an estranged nightingale.

But you were food for ruin and whittled yourself to nothing

for the sake of fleeting, aimless dreams.—“Your Childhood in Menton,” translated from the Spanish by Greg Simon and Steven F. White

I made my way to Cotton Club, one of the many jazz clubs Lorca frequented and a large part of why he fell in love with Harlem and Black culture. Unfortunately, the bouncer told me there wasn’t a show that night—maybe I could come back for Brunch and Gospel on Sunday. “Not as much jazz as there used to be,” he said. “A lot of covers.”

I followed Lorca’s contrails south and found that his New York had been demolished and substituted. Near Battery Place, where there was, during his time, an aquarium, there is only a fish-themed carousel. Where he wrote about “shadowy people who stumble on street corners,” I found parents entertaining stock-still children and a young couple chin-deep in a mushroom trip. I obliged the couple when they asked for a cigarette and then walked north to Battery Park City, entering Brookfield Place, a mall with a subway-station appendix. Omega, Bottega Veneta, Fendi, an Equinox. The atrium’s centerpiece was an LED installation entitled Luminaries, which, their website claims, through “the individual and collective act of wishing creates a communal and celebratory tradition.” Visitors are prompted to place their hands atop one of three squat white columns in the middle of the room and make their wish. A moment later, upon removing their hands from these “wishing stations,” a constellation of plastic cubes overhead light up in a display of pastel phosphorescence. A boy in a Patagonia vest indulged his curiosity, placing his hand on one of the columns.” Above him, a grid of cubes lit up—wish granted.

We will have to journey through the eyes of idiots,

open country where the tame cobras hiss in a daze,

landscapes full of graves that yield the freshest apples,

so that overwhelming light will arrive to frighten the rich behind their magnifying glasses—

—“Landscape of a Pissing Multitude (Battery Place Nocturne),” translated from the Spanish by Greg Simon and Steven F. White

The kid and his father started laughing. The overwhelming light wasn’t all that frightening, apparently. In the far corner, a custodian rode an escalator up and down, dragging his mop across the escalator’s steel divider, cleaning something that is almost never dirty. The capitalist economic system, according to Lorca, was one “whose neck must be cut.” Sure thing, my man. I’m on it. Exiting the mall, I heard the drone of a helicopter; it was affixed to the sky as if by flypaper, loudly headed nowhere.

Lorca said he was “lucky enough” to witness the Wall Street crash. One could say he didn’t like bankers and was angry even at their suicides. “Rivers of gold flow there from all over the earth, and death comes with it. There, as nowhere else, you feel a total absence of the spirit.” And on this Wall Street, where Lorca situated his poem “Dance of Death”—a true death from which there is no resurrection—I found a team of exultant rats tearing into a Sweetgreen bag. Life had officially been affirmed! There was something doleful about the whole scene, of course, but the rats had a winter to endure.

This place isn’t foreign to the dance, I say it.

The mask will dance between columns of blood and numbers,

between hurricanes of gold and moans of idled workers,

who will howl, dark night, for your time without lights.

—“Dance of Death,” translated from the Spanish by Pablo Medina

The Brooklyn Bridge is the subject of one of Lorca’s nocturnes, “City without Sleep,” in which, as the title implies, no one sleeps. On my travels at around midnight, the bridge was deserted, windswept, and intolerable. Lorca, a vain sartorialist of sorts, must have walked this walk in the summer, likely donning a linen suit. Fatigued by the initial incline, I stopped and checked my phone. A friend who knew about my strange project had sent me a photo of Lorca’s memorial in Granada. Six years after Lorca returned to Spain from New York, he was executed. Though the exact circumstances surrounding his execution remain unknown, it was a civil war, the nationalists wanted a return to the monarchy, and he was a gay socialist; these things tend to happen. Lorca mentions assassination nine times in the collection. In one case, he writes: “I knew they had murdered me.” Poet in New York would be published posthumously, and his remains have yet to be found.

I’ve already said it.

No one sleeps.

But if at night someone has an excess of moss on his temples,

then open the trap doors so the moon lets him see

the false cups, the poison, and the skull of the theaters.

—“City Without Sleep (Nocturne of the Brooklyn Bridge),” translated from the Spanish by Pablo Medina and Mark Statman

Upon returning to Granada, Lorca said, “New York is something awful, something monstrous … Besides black art, there is only automation and mechanization.” If what he found in my city was “the world’s great lie,” he embodied that fabrication. During his time in New York, in his letters to friends and family Lorca is delirious and congenial, taking a tone at odds with that of his work. He beautifully exaggerates his willingness to learn English, he compliments the several friends and academics who go to great lengths to take care of him, he makes repeated mention of the beautiful girls he’s meeting (eliding his sexuality, maybe; I can’t tell), and when he’s asked to return home for a wedding, he writes that it would be best for him to stay just a while longer.

Zain Khalid is a writer from New York.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/fcO2BP3

Comments

Post a Comment